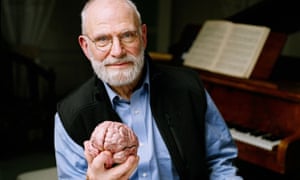

Oliver Sacks, who has taught us so much, now teaches us the art of dying

Ranjana Srivastava

Death is never easy. But Oliver Sacks shows us an approach that views life as a welcome gift rather than bemoaning death as a medical failure

Like millions of readers I had a lump in my throat as I read Oliver Sacks reveal his diagnosis of terminal cancer earlier this year. Every doctor aspires to be a little like Sacks whether for his sharp intellect, his obvious humanity or his exquisite writings that go to the core of what it means to be human and frail.

In February he calmly declared that metastatic melanoma affecting his liver meant that his luck had run out. I found it hard to share his calm but then like the genial, grandfather-figure he is, he reassured us, oncologists and all, that he still felt intensely alive, wanting to “deepen my friendships, to write more, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.”

His mention of finding a new focus and perspective resonated with me – it is as close to a universal finding as there is in clinic, where ordinary individuals and famous people all say that cancer forced them to contemplate their life and legacy.

It’s not always pretty, I concede. Cancer triggers joyful marriage but also bitter divorce. It unites bickering siblings but also tears apart those previously contented. It fosters a peaceful reckoning and loving coexistence but equally tempestuous anger and unrelenting sorrow. All I can say is letting go is hard. Actually, it sucks. Watching the march of thousands of such patients, I keep thinking it must be indescribably difficult to bear if it is so difficult just to watch from the vantage point of an unrelated oncologist, who at best catches only glimpses of the struggle patients face every day.

The lump in my throat grew larger this weekend when Oliver Sacks declared that his disease had inevitably returned despite liver embolization and immunotherapy, the holy grail of melanoma treatment. Oh no, I thought glumly, not you too, as if the greatness of being Oliver Sacks were enough to outsmart rapidly dividing melanocytes. Sadly no. The venerable figure that he is, I can just about picture him telling a group of despondent young residents that it would be naive to think that a terminally ill doctor might avoid the fate of many of his patients.

Oliver Sacks dying of metastatic melanoma may have been just another story of misfortune in a world spilling over with bad news were it not for something that caught my eye towards the middle of his column. He lists symptoms of nausea, loss of appetite, chills and sweats and a pervasive tiredness, all cardinal signs of worsening cancer. He tells us he is still managing to swim although the pace is slower as he pauses to breathe. And then, he says something utterly obvious and yet, thoroughly remarkable: “I could deny it before but I know I am ill now.”

In a piece of achingly beautiful writing, this observation may bypass the typical outsider but as an oncologist, it struck me as the essence of what it takes to die well – the concession that all the well-intentioned therapy in the world can no longer prevent one from going down the irreversible trajectory of death.

This recognition allows patients to halt toxic treatment, opt for effective palliation and articulate their goals for the end of life. It permits their oncologist to open up new conversations that don’t include the latest million-dollar blockbuster therapy with a bleak survival curve but do mention the therapeutic benefit of teaming up with hospice workers to write letters, preserve photos and record memories. I would say that this candid admission from a patient is the difference between bemoaning death as a medical failure and viewing life as a welcome gift.

He had determined that there was to be no conversation about her progressive cancer or the fact that she lay dying. Her experience was unacceptable yet the impasse dreadful and ethically troubling.I found myself thinking of a former patient who came into hospital dying of liver failure from metastatic bowel cancer. Her jaundiced skin was practically glowing and she had a resulting insatiable itch. There was not a single comfortable position she could find and it soon became clear that that she needed continuous sedation for comfort. But before I sedated her I needed to be sure that she understood her terminal condition, difficult given that the liver failure was causing agitation. The problem was that her husband was permanently stationed at her bedside and would not hear of me mentioning any bad news to the patient.

One morning her husband was delayed but she needed urgent attention so I walked in alone to find a clearly distressed patient. Looking surreptitiously around the room, and temporarily alert, she whispered, “What is happening to me?”

I sat down and held her hand, noting a trail of bleeding scratch marks.

“Do you want me to tell you?”

Before she could answer, her husband roared from behind me, “How dare you plot to scare my wife like that in my absence? Get out!”

As I covered my ears against the litany of abuse, the patient’s terrorised eyes briefly rested on mine. Sorry, they seemed to say, I am really sorry. Refusing to be mollified by the palliative care staff the man virtually dragged his dying wife home. He made a mockery of her end of life care and left me with a searing memory of my failure to help a dying patient. But I also try to remember that he loved her and just couldn’t bear the thought of letting her go. Letting go is hard.

Doctors fail patients in various ways but in some ways it is easier to fail patients when they or their family deny impending death. They are the ones who deserve our greatest consideration and patience but the truth is that it’s taxing enough to treat intractable pain, omnipresent nausea or pervasive melancholy without having to take on the onerous task of saying, “Believe me, you really are dying.”

Unlike suturing or locating a pulse, dealing with death does not become easier with time. If you care about your patient, it always hurts. It hurts when you fail to cure them and it hurts when you fail to help them die. Patients who can get even part of the way to acknowledging their mortality ultimately do themselves, their relatives and even their oncologists an untold favour.

But of course, it’s one thing to understand your mortality and quite another to articulate your feelings for the world to scrutinise. At his diagnosis Oliver Sacks wrote, “I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude.” Those insightful words brought inspiration to untold patients.

But the doctor who brought to us the man who mistook his wife for a hat isn’t about to mistake death for what it is. Now he reminds us with all the poise and dignity we have come to expect of him that there is value in embracing our mortality, that there is an art to dying, and before he goes, he might just show us how. For this and so much more, we owe him.

In a poignant essay, renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks reveals he has an incurable cancer: http://cnn.it/1Acnfdb

In a poignant essay, renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks reveals he has an incurable cancer: http://cnn.it/1Acnfdb

On The Move

ON THE MOVE: A LIFE 預計2015年5月出版

by Oliver Sacks

by Oliver Sacks

An impassioned, tender, and joyous memoir by the author of Musicophilia and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

Coming May 2015

Also available from Random House Audio

Also available from Random House Audio

Jacket image: TK

Jacket design by Chip Kidd

Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher, New York

Jacket design by Chip Kidd

Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher, New York

(Pre-order) Purchase from: Amazon | Barnes and Noble

On The Move: A Life

When Oliver Sacks was twelve years old, a perceptive schoolmaster wrote in his report: “Sacks will go far, if he does not go too far.” It is now abundantly clear that Sacks has never stopped going. From its opening pages on his youthful obsession with motorcycles and speed, On the Move is infused with his restless energy. As he recounts his experiences as a young neurologist in the early 1960s, first in California, where he struggled with drug addiction and then in New York, where he discovered a long forgotten illness in the back wards of a chronic hospital, we see how his engagement with patients comes to define his life.

With unbridled honesty and humor, Sacks shows us that the same energy that drives his physical passions—weightlifting and swimming—also drives his cerebral passions. He writes about his love affairs, both romantic and intellectual; his guilt over leaving his family to come to America; his bond with his schizophrenic brother; and the writers and scientists—Thom Gunn, A.R. Luria, W.H. Auden, Gerald M. Edelman, Francis Crick—who influenced him. On the Move is the story of a brilliantly unconventional physician and writer—and of the man who has illuminated the many ways that the brain makes us human.

Oliver Sacks is a practicing physician and the author of twelve books, including The Mind’s Eye, Musicophilia, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Awakenings (which inspired the Oscar-nominated film). He lives in New York City, where he is a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine.

Oliver Sack’s An Anthropologist on Mars, Awakenings, Hallucinations, The Island of the Colorblind, The Mind’s Eye, Musicophilia, Seeing Voices, and Uncle Tungsten are available in Vintage paperback, as is Vintage Sacks, a collection of his finest work.

【書評:薩克斯不會停下來】文/周達智 (tc)

全文看:https://goo.gl/8KigoY

//薩克斯自傳以 "On The Move” 為題明志,取自友人 Thom Dunn 同名詩作,首次披露私人生活。絕少讀者猜得出,封面像香煙廣告模特兒的美男子,就是大鬍子醫生。筆者問過幾位朋友,全未聽說過薩克斯是同性戀者;更難想像,一生投身腦科學的紐約大學教授,當年曾沉迷健身,創下深蹲舉重 600 磅的加州紀錄。身在嬉皮士年代的加州,腦科學家不諱言經常進行精神科藥物實驗,曾有四年廢寢忘食,「被腦部的快感中心操縱」。薩克斯自言「大情大性,為一切愛好投入激烈的熱情,絕不保留」,青春的狂燄曾經燃燒過甚麼,相信自傳難以盡錄。//

//大鬍子薩克斯醫生 Oliver Sacks 著作等身,以敏銳的筆觸和深邃的關懷,重現神經心理學案例中每一個人的生命和思想世界,揭示大腦和思維之間的奧秘,成為家傳戶曉的暢銷書作者及腦科學家。如今滿臉祥和,受千萬讀者愛戴的他,自少嚮往到處闖盪的自由和力拔山河的強壯。那位愛在週未換上黑色皮褸,讓「地獄天使」車黨也視為一伙的年青醫生,18 歲前往牛津就讀前換來第一部鐵騎;試車時老爺車突然鎖起油門,才知道掣動器也失修。他寧願沿途高呼讓路,在敦倫的攝政公園繞圈至燃油秏盡,也不肯將車拉倒停下來。//

wikipedia

奧利佛·薩克斯(Oliver Sacks,1933年7月9日-),英國倫敦著名生物學家、腦神經學家、作家及業餘化學家。他根據他對病人的觀察,而寫了好幾本暢鍚書。他側重於跟隨19世紀傳統的「臨床軼事」,文學風格式的非正式病歷。他最喜愛的例子為盧力亞著作的記憶大師的心靈。

他在牛津大學王后學院學醫,後到美國加州大學洛杉磯分校神經科執業,1965年移居紐約,從醫並教書。他在愛因斯坦醫學院擔任臨床腦神經教授、紐約大學醫學院擔任腦神經科客座教授及為安貧小姊妹會擔任顧問腦神經專家。

薩克斯只在他的病例中記述少量的臨床數據,主要集中在病人的經歷上(其中一個病例為他本人)。其中許多病例均無法治癒或接近無法醫治,但病人會以不同方式改變他們的病情。

他最著名的著作——《睡人》(Awakenings,後來改編為同名電影無語問蒼天)講述了他在多名1920年代的昏睡病嗜眠性腦炎病人身上試用新葯左旋多巴的經歷。這同樣是英國電視連續劇Discovery首集的主題。

他的另一本書描述柏金遜症的各種影響以及杜雷特症的個案。《錯把帽子當太太的人》是描述一位視覺辨識不能症狀的人(此病例是1987年麥可·尼曼創作的歌劇的主題),《火星上的人類學家》是關於天寶·葛蘭汀(一位高功能自閉症的教授)的描述。薩克斯的著作被翻譯成包括中文在內的21種語言。

作品列表[編輯]

- 《偏頭痛》(Migraine) (1970年)

- 《睡人》(Awakenings) (1973年);范昱峰譯(1998年)台北:時報文化,ISBN 957-13-2757-3。

- 《單腳站立》(A leg to stand on) (1984年) (薩克斯在一場意外後無法控制自己雙腳的經歷)

- 《錯把太太當帽子的人》(The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) (1985年);孫秀惠譯 (1996年),台北:天下文化。

- 《看得見的聲音》 (1989年) (Deaf culture and sign language)

- 《火星上的人類學家》(Anthropologist on Mars) (1995年); 趙永芬譯,台北:天下文化。

- 《色盲島》(The Island of the colorblind) (1997年) (一個島嶼社群上的先天性完全色盲);黃秀如譯(1999年),台北:時報文化。

- 《鎢絲舅舅─少年奧立佛.薩克斯的化學愛戀》(2001年);廖月娟譯(2003年)台北:時報文化。

- Oaxaca Journal (2002年)

- 《腦袋裝了2000齣歌劇的人》(Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain)(2008年)廖月娟譯,台北:天下文化

- 《看得見的盲人》(The Mind's Eye) (2012年) 廖月娟譯,台北:天下文化

外部連結[編輯]

奧利佛·薩克斯的個人網頁 (英語)

奧利佛·薩克斯的支持者的網頁 (英語)

The Fully Immersive Mind of Oliver Sacks於Wired 10.04

這本書的中文本【鎢絲舅舅】似乎受忽視......

|

|

▼ 射線

射線

我在亞柏舅的閣樓初次見識什麼是陰極射線。他有一個強力真空泵浦,還有一個感應圈--這是一個高約六十公分的圓柱體,上面密密麻麻地綑著長得不得了的銅線,平躺在桃花心木做的絕緣木座上。感應圈上還有兩個可以移動的黃銅電極,感應圈一轉動,電極間剎時冒出火花。這小小的電光石火像是從佛蘭肯斯坦博士(科學怪人的創造者)的實驗室跑出來的金蛇。亞柏舅把這兩個電極分開到無法冒出火花的地步,再連接上一根長約九十公分的真空管。他把通電的真空管減壓,管內於是出現一連串奇異的景象:一開始是一道道閃爍不定的紅光,絢麗如北極光,只是小多了,接著燦爛的亮光充滿了整支管子,明亮輝煌。壓力繼續下降,真空管就出現一個又一個晶亮的圓盤,圓盤間則是黑黑的一段。最後,大氣壓降到千分之十的時候,管子裡就變得烏七抹黑,末端開始出現明亮的螢光。舅舅說,管中已充滿陰極射線,陰極放出許許多多小小的粒子。這些粒子以光速的十分之一飛行,活躍度很高,如果和陰極盤相連,就算是鉑箔,也會被燒到紅熱。這種肉眼看不見卻能穿透骨肉的射線教我心生恐懼(兒時的我也怕手術用的紫外線)。我擔心陰極射線會從管子裂縫跑出來,射中在黑暗閣樓中的我們。

亞柏舅要我別害怕。他解釋說,陰極射線頂多只能穿透六、七公分的空氣,另一種射線的穿透力就強多了,也就是倫琴(Wilhelm Roentgen, 1845-1923)在一八九五年用這種陰極射線管做實驗時發現的射線。倫琴用黑色的卡紙把陰極射線管包裹起來,以避免漏光。結果,每一次電管放電,實驗室另一頭的螢光屏上就會現閃亮一下。這亮光讓他十分震驚。 倫琴當下決定放下其他研究工作,專心研究這個完全令人想不到又很奇妙的現象,一而再、再而三地重複這個實驗,直到他確定這不是錯覺為止。(他告訴他太太說,如果沒有讓人信服的證據,他是不會說出來的,否則別人會以為他發瘋了。)在接下來的六個禮拜,他不斷實驗,看看這種奇妙的新射線有什麼特性。他發現這射線顯然不像可見光,不會折射或衍射[1]。他用手邊現有的各種物體做實驗,發現這射線能穿透最常見的東西,使光屏發光。倫琴把他自己的手放在光屏前面,赫然發現那手掌變成駭人的白骨。同樣地,放在密閉木匣的金屬砝碼也在射線的照射下露出原形。看來,這種射線比較容易穿透木頭和肌肉,但難以穿透金屬或骨頭。倫琴發現,這射線也會使照相底片感光,他於是在自己發表的第一篇論文中加了一幀X射線拍到的照片(倫琴當時無法確定這種射線的性質,故稱之為X射線),也就是他太太手掌的X光片。她的手骨清晰可見,連指頭上戴的婚戒都顯示出來了。 一八九六年一月一日,倫琴在一本小小的學術期刊上發表他的發現,並附上他最先照的幾張X光片。不到幾天,全世界各大報都報導了這個聳人聽聞的消息。這個發現引起軒然大波,生性害羞的倫琴因而心生恐懼。一月下旬,他第一次公開出面做了報告,從此就不再討論X射線,重拾先前暫時放下的研究課題。他就是喜歡一個人靜靜地做研究。(由於X射線的發現,他在一九○一年成為榮獲諾貝爾物理學獎的第一人,他卻拒絕發表得獎演說。) 然而,這種實用的新科技隨即處處可見,世界各地也開始利用X光機來診斷,以偵測骨折、異物、膽結石等。到了一八九六年底,有關X射線已有一千篇以上的論文報告。倫琴發現的X射線不僅對醫學和科學有重大衝擊,更驚動世人,讓人大發奇想。只要花個一、兩塊錢就可以購買九週大的嬰兒X光片,「骨骼細部因而一覽無遺,骨化的階段[2],順便看看肝臟、胃、心臟在哪裡。」 大家覺得X射線想必有種神奇的力量。人們生活中最隱私、最秘密的角落將會因為這種射線的出現而曝光。精神分裂症的患者認為X射線可以看透他們,知道他們在想什麼,甚至影響他們的思考。還有人從此失去安全感,覺得無所遁形。報紙上一篇社論擲地有聲地論道:「你可以用自己的肉眼看到別人的骨頭,也可透視二十公分厚的木頭,知道後面有什麼。不用說,這樣被『看光光』實在丟臉之至。」市面上還出現包覆鉛皮的內衣褲,以免「私處」在射線的照射下被人看到了。《攝影》(Photography)雜誌還曾刊登一首流行歌謠,最後一段是:

聽說,目光因此

可以穿透斗篷、禮服,甚至在你下面逗留, 這倫琴射線真真猥褻、下流。

我叔叔雅茨查克在感冒大流行那幾個月曾和爸爸一同照顧病人。第一次世界大戰一結束,他就投身放射醫學。爸爸告訴我說,有了X光的神力,叔叔的診斷如虎添翼,即使是最小的病理變化也察覺得出來,真是明察秋毫。

叔叔的診療室,我曾去過幾次。叔叔會讓我看他的儀器,並為我介紹這些東西的用途。早期的X光機,X射線管是露出來的,現在則看不到了,置於一個突出長長的且隆起一塊的黑色金屬盒--這東西狀似巨鳥鳥喙,看來很可怕,像會把人吃了似的。雅茨查克叔叔帶我去他的暗房,看他沖洗剛剛照的X光片。暗房幽暗,只留一盞紅色的燈。我看到大大的片子上顯露出股骨(大腿骨)的輪廓。那地方看起來幾乎是半透明的,很美。叔叔指出骨頭上有一條髮絲般細的灰線,那就是骨折的地方。 叔叔說:「你在鞋店看過X光屏了吧。這東西可以透視你鞋子下的腳骨活動起來如何[3]。我們也可用特別的顯影對比劑來看看身體的其他組織--神奇吧?」 他又說:「你還記得做機械工人的史匹格曼先生嗎?你爸爸懷疑他可能有胃潰瘍,要他來我這兒做檢查。我打算給他吃『鋇餐』。你想看看嗎?」 「我們用的是硫酸鋇,」叔叔一面說一面攪拌一種白白的黏稠狀的液體,解釋說:「這是因為鋇離子很重,X射線幾乎無法穿透,因此可做為造影劑。」聽他這麼一說,我不禁異想天開,問道可不可以用更重的離子,讓病人吃「鉛餐」、「汞餐」或者「鉈餐」--這些離子都重得不得了,當然也有致命之虞。「金餐」或「鉑餐」也很有意思,不過可能太貴了,教人吃不起。我問道:「『鎢餐』如何?鎢的原子比鋇重多了,而且鎢沒有毒,也不貴。」 我們進入診療室,叔叔將我介紹給史匹格曼先生。他記得看過我,一個禮拜天早晨,我陪爸爸出診的時候。「他不正是薩克斯醫師最小的兒子奧立佛,想當科學家的那一個?」叔叔請史匹格曼先生在X光機和螢光屏的中間站好,請他吃下「鋇餐」。史匹格曼先生用湯匙把那白色黏稠狀的液體送入口中,吞下去。我們盯著螢光屏。鋇劑從他喉嚨下去,進入食道之後,可以看到他腸胃道慢慢蠕動,把鋇劑推到胃裡。我從陰森森的背景看到史匹格曼的肺,那肺隨著每一次呼吸擴張、收縮。最令人害怕是,有一個袋子在他的體內悸動。叔叔說,這就是心臟。 有時,我不禁好奇,這種射線是不是像另一種感官。媽媽告訴我,蝙蝠會發出超音波,昆蟲能看到紫外光,響尾蛇則有紅外線感受器。此時此刻,看著史匹格曼的五臟六腑被「X光之眼」的透視下無所遁形,我很慶幸自己的眼力不像什麼都能看透的X光。由於人體的自然設計,我們只看得到某個波長範圍內的光。 雅茨查克叔叔就像大偉舅,對摯愛之物的理論基礎和歷史發展都很有興趣。他有一個小小的「博物館」,收藏了舊的X光機、陰極射線管,還有三支在一八九○年代用的、長長的、易碎的射線管。他說,早期的管子沒有考慮到放射線的防護,其實那時世人也還不了解放射線的危險。 然而他又說,X光問世才幾個月,就傳出有人受到傷害的消息。發明消毒劑、開啟無菌外科手術紀元的李斯特(Joseph Lister, 1827-1912)早在一八九六年就對大眾提出警告,可惜大家充耳不聞[4]。 顯然,X射線有強大的能量,而且能產生熱能。從另一方面來看,儘管X射線有穿透力,穿透空氣的距離仍然有限,不像無線電波,可以用光速的速度越過海峽。電波也是有能量的。這種射線是可見光的親戚,但很奇特,能讓人形消骨毀。我陷入奇想:小說家威爾斯(H. G. Wells, 1866-1946)是否因為這種射線得到靈感,讓他的小說《星際戰爭》(The War of the Worlds)中的火星人使用熱線槍大肆殺戮。這本書的問世只是比倫琴發現X射線晚兩年而已。威爾斯描述火星人的熱線「像鬼魅一樣」、「像隻隱形的、熾熱的指頭」、「看不見的熱武器,讓人無處可逃」。用拋物鏡反射出來的熱線,可熔化鐵和玻璃、把鉛塊變成液體、讓水爆炸在剎那間化為蒸氣。威爾斯又說,那熱線越過鄉間的速度「飛快如光」。 |

![「 In a poignant essay, renowned neurologist @[212505698805486:274:Oliver Sacks] reveals he has an incurable cancer: http://cnn.it/1Acnfdb 」](https://fbcdn-sphotos-e-a.akamaihd.net/hphotos-ak-xpf1/t31.0-8/p403x403/10629454_10153373658666509_4647708670238208587_o.jpg)

沒有留言:

張貼留言