萊蒙托夫

《莱蒙托夫》,(俄)伊凡诺夫/著,克冰/译,上海:上海译文出版社,1993.6。

莱蒙托夫小组收藏

俄国诗人莱蒙托夫诞辰(1814年10月15日)

追尋可能對話的聲音 - 閱讀俄國作家萊蒙托夫

|

| 追尋可能對話的聲音 - 閱讀俄國作家萊蒙托夫 |

萊 蒙托夫(Mikhail Lermontov,1814-1841)是始終沒有被台灣讀者真正閱讀過的俄國經典作家。大部分涉獵過俄國文學的讀者絕對認識普希金 (Alexander Pushkin,1799-1837),卻可能跳過萊蒙托夫,直接進入果戈里(Nikolai Gogol-Yanovski,1809-1852)、屠格涅夫(Ivan Turgenev,1818-1883)、杜思妥也夫斯基(Fyodor Dostoevsky,1821-1881)和托爾斯泰(Lev Tolstoy,1828-1910)的殿堂,原因可能出在萊蒙托夫沒有繁體中文譯本,也有可能因為萊蒙托夫不很靠近悲憫「小人物」的俄國文學傳統路線, 因而沒有留給我們的讀者太多機會去認識。

俄國文學的心靈曲徑

20世紀初以布洛克(Alexander Blok,1880-1921)為首的俄國象徵詩派曾大聲疾呼,俄國文學不應該只有普希金為代表的理性文學傳統,在這條正統文學大道旁其實存有一條小徑,它撩撥你的心,拐你進入森林祕徑,它彎曲分岔,難以一窺究竟。

這 條小徑在俄國就是萊蒙托夫開闢的文學傳統,說穿了,它探究的是深邃的人類心靈。走在這條曲徑上,風光旖旎詭譎,礫石遍布,即使如此,還是有人偏向此路行, 那是杜思妥也夫斯基跟隨的腳步,在那裡跳動的心臟被剖開來訴說,血汩汩流,懊悔的情感左右一切,讀者聽也罷,不聽也罷,作者總是不得不說。

詩人曼德爾施坦姆(Osip Mandelstam,1891-1938)曾言:「我把普希金和萊蒙托夫拿來對比,左看右看都看不出兩人有血緣關係。」他這是笑說俄國文學史家喜歡將兩人湊在一起。

普 希金一死,萊蒙托夫即以〈詩人之死〉一詩痛罵俄國朝廷虛偽無恥,遭到流放高加索的懲罰,至此他接過俄國詩壇大旗,走出俄國文學黃金大道。就這點聯繫了兩人 的血緣,此外他們都不為沙皇喜歡(同是尼古拉一世),都被流放過,都在決鬥中被殺,也都英年早逝,際遇確有形貌的相似,但講到文學氣質,兩人沒有半點相 似:普希金明亮樂觀,萊蒙托夫陰鬱多疑;普希金文風敦厚和諧,萊蒙托夫譏諷尖銳;普希金理性,萊蒙托夫神祕,兩人一明一暗,互為表裡,共同構成俄國文學整 體面貌。

惡魔式的孤獨

我喜歡萊蒙托夫,因為他總是鬥志激昂地面對敵人,而他的頭號敵人就是孤獨。

「孤 帆遠影成白點/青藍海霧渺渺間!/它去遠方國度追尋什麼?/又拋卻什麼在熟悉故鄉?/海浪翻滾,狂風呼嘯,/桅桿傾折,嘎吱作響……/唉,它不是追尋幸福 /也不是逃離幸福!/……/騷動不安的帆呀,卻祈求風暴來襲,彷彿風暴中才有平靜!」

這首〈帆〉(1832年)是萊蒙托夫早期代表作,孤獨彌漫字裡行間, 反映一生宿命,但「彷彿風暴中才有平靜」一句卻顯現積極心態──渴望生活,而且是狂暴的生活,他用孤傲對抗孤獨,用全部的文學生命對抗孤獨。

追溯孤獨的根源是在童年。窮軍官爸爸和富家女媽媽的不對稱婚姻,讓外婆嫌棄女婿,但極寵愛外孫。三歲母親死,父親被迫離去,小萊蒙托夫跟著外婆在南部莊園過著優渥的貴族生活,然而,錢買不到幸福的遺憾也深種其心,孤獨於是如影隨形。

他寫詩作畫,耽溺幻想,那是情感宣洩的場所。十四歲他開始創作最貼近內心的形象──永世孤獨的惡魔。

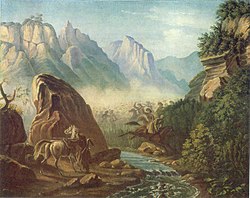

《惡 魔》是萊蒙托夫筆下最具魅力的形象之一,這部敘事詩他至少寫了八個版本。桀驁不馴的惡魔曾是天使,不服膺上帝威權,遭逐出天堂,貶為惡魔。他掌管人世之 惡,恣意妄為,竟愛上格魯吉亞公主。惡魔誘惑公主,在親吻中將她灼燒致死,想藉此占她為己有,但天使出現,將公主帶往天堂,留下惡魔在塵世繼續無盡的孤獨 旅程。

孤獨是萊蒙托夫的病灶,是涵養他叛逆性格的土壤。我們無法確定,走過年輕歲月,這病是否會不藥而癒,屆時這位外表不脫稚氣,眼睛卻閃 著冷光,個性高傲,說話帶刺的詩人作家,能否以輕舟越過風暴的心態,迎接生命另一番風景。關於此,答案是個謎,因為他在二十七歲時決鬥身亡,又是好嘲弄的 個性使然,正如他筆下的佩喬林,總是為自己樹立敵人,而非朋友。

渴望自由一如生活

萊 蒙托夫渴望自由,作品中展現出對充滿生命力的自由的渴望。另一代表作敘事詩《童僧》講一名稚齡六、七歲的格魯吉亞男孩被俄軍俘獲,送進修道院當服侍見習 僧,強權者意圖以高牆圍籬和誦經聲抹去番童記憶,馴服蠻性。所有這一切都是枉然,童僧以緘默對抗外界,後趁隙逃出,躲進林中三日,被發現帶回時已奄奄一 息。

死前他向老修士告白:修道院生活即使安逸,於他都是牢籠,他不願屈服。在外三日是他被俘以來唯一的生活經驗,他感受到青春和美的悸動,還有黑暗和野獸環伺,以及面對死亡的恐懼,唯有這些感覺才是生活,才是自由。

有著超齡成熟心智的《童僧》,一如〈帆〉,與其在冰冷的死寂中苟活,他選擇「向風暴裡尋求平靜」。

《當代英雄》的多重敘事交響

萊 蒙托夫長篇《當代英雄》由五個中短篇故事加上兩篇序文構成,文本順序是:作者序文(再版時加上)、〈貝拉〉、〈馬克辛.馬克辛梅奇〉、日記序文、〈塔 曼〉、〈梅麗公爵小姐〉、〈宿命論者〉。這並非按事件的時序安排,實際時序是:〈塔曼〉、〈梅麗公爵小姐〉、〈貝拉〉、〈宿命論者〉(第三、四時序相近, 先後有疑義)、〈馬克辛.馬克辛梅奇〉、日記序文、作者序文。作者這樣安排自有用意。小說前兩篇故事裡有兩位敘事者(年輕無名軍官與老上尉馬克辛.馬克辛 梅奇),透過他們,讀者方得知主角佩喬林的生平事蹟,這種方式為側寫,而後三篇故事出自佩喬林日記,就是第三位敘事者佩喬林的現身說法,其中摻以大量的獨 白和心理剖析。

俄國評論家認為這種結構是為了由外而內逐漸探入主角內心,以立體呈現人物的複雜個性和心理。萊蒙托夫藉此創造了獨特的多重敘事聲音手法,且不只讓三位敘事者發聲,在這之上還有作者的聲音,它穿梭在各章節,透過不同角色出聲,讀者須細心諦聽方能聽到。

〈貝 拉〉是由一位年輕的無名軍官以第一人稱敘說,他教養良好,喜愛文學,因公前往高加索山區,以遊記體呈現沿途景色,並記錄旅伴老上尉馬克辛.馬克辛梅奇(第 二個敘事聲)所談的:奇人佩喬林誘拐當地公主貝拉的愛情冒險──這是故事中的故事,但做為主題。在兩個敘事聲中交集出佩喬林這位主角的輪廓和評價,此人能 洞悉人性,不動聲色地驅使他人達成自己的目的,且不用負上擄走貝拉的責任。這宛如惡魔的人物,同時又極富魅力,周圍的人即使知道他不對,卻又不能不愛他, 令人聯想到杜思妥也夫斯基筆下《群魔》的主角斯塔夫洛金。

萊蒙托夫天才之處,是他在佩喬林形象差不多底定之時,安排佩喬林自己出來說話。佩 喬林個性矛盾多疑,冷漠外表下暗藏狂熱情感,但在感動瞬間後又會變得無情,總的說來他是個懷疑主義者。好譏諷的習慣既是出於克制不了的惡意,也因為看透上 流社會的浮華矯飾。這個惡魔般的人物是否就是作者的化身?從小說問世以來,這方面的討論不斷,逼得萊蒙托夫不得不在作者序文裡寫出「我們的讀者太天真」的 名言,以釐清小說人物與作者之間的差別。

日記裡獨白與對話交錯呼應,若能釐清對話,亦可以看清獨白本質,從某個角度來說,佩喬林的獨白是把他人意識視為自我內心對話對象的架構下進行,從這角度看,佩喬林需要對話的聲音,他也總是在尋找可能對話的對象。

日記裡佩喬林的主要對話者有七個:〈塔曼〉裡的韃靼女人「水妖精」,〈梅麗公爵小姐〉裡的士官生格魯什尼茨基、梅麗公爵小姐、維爾納醫生、舊情人薇拉,最後是〈宿命論者〉中的烏里奇中尉;第七個對象就是他內心的「另一個我」,這穿插在日記每個角落。

日 記第一篇故事是〈塔曼〉,佩喬林初到高加索的懸疑冒險,主調是跟蹤、偷窺、豔遇與誤解。女主角「水妖精」是個韃靼女人,周身是謎,深深吸引佩喬林。他問: 「妳在屋頂做什麼?」答:「看風從哪裡來。風在哪,幸福就在哪。」他說:「難道妳可以用歌聲招來幸福?」她回:「哪裡有歌,哪裡就有幸福。」他說:「千萬 別給自己唱來悲傷喲。」她答:「哪裡沒好事,哪裡就有壞事。好壞相差也不遠。」他又問:「誰教妳唱這首歌?」答:「沒人教,想到什麼唱什麼;誰該聽,他就 聽得明白,誰不該聽,就聽不明白。」他又問:「妳教什麼名字?」答:「誰幫我施洗禮,誰就知道。」他不死心再問:「那是誰施洗禮的?」她答:「我怎麼會知 道。」這真是一段經典對話,好鬥的佩喬林始終處於下風(也是全書唯一一次),卻更使他為之迷倒。「水妖精」隨遇而安又不隨波逐流的態度正是佩喬林嚮往的, 從塔曼開始佩喬林展開探索命運的旅程。

日記最末篇〈宿命論者〉的對話關係更是特殊,宿命論代表的烏里奇中尉和挑戰命運的佩喬林,兩人從牌局 一直鬥到命運本身,烏里奇確實是一位可敬的對手,他傳奇性地出場演練命運天注定,差點讓佩喬林相信了,然而經過反覆思辨和親身試驗之後,佩喬林還是確定自 己不走命運安排的路。小說在此倏地告結,留下無盡思索,此篇乃是俄國小說的傑作。如果將這七種回聲串起,可以發現這為小說中哲思性的「我不願安於這種命 運」的主旋律,適時敲出了浮華世界多變的韻律感:黑海的鹹騷、溫泉鄉的硫磺、淑女的清淡幽香、貴婦的濃郁體香、手槍硝煙後的輕煙、冷酷的搏命賭注……

惡 魔性格的人物總是特別吸引讀者關注,他遊走在道德和常規的邊界,所到之處帶給別人不幸,卻不減魅力。佩喬林就是這樣一位黑暗「英雄」,他是時代之子,身處 的環境造就他這朵社會之惡的花朵,萊蒙托夫寫出來以供世人警惕,然讀者是否真能看懂?至今這問題依舊得由小說最前面的序文來回答。 ●

---

Wikipedia

米哈伊爾·尤列維奇·萊蒙托夫(俄語:Михаил Юрьевич Лермонтов;1814年10月15日-1841年7月27日),俄國作家、詩人。被視為普希金的後繼者。

1830年3月,莫斯科寄宿學校改為普通中學,萊蒙托夫請求退學,並前往斯托雷平家 族的謝列德尼科沃莊園,同年考入莫斯科大學。在友人A·M·韋列夏金娜的家中結識E·A·蘇什科娃,並與之熱戀。這時期開始抒情詩的創作,但他不斷地移情 別戀,又愛上了劇作家伊萬諾夫的女兒伊萬諾娃。1832年,前往聖彼得堡。同年11月通過近衛士官生入學考試。1835年,成為禁軍驃騎兵團騎兵少尉。 1837年1月27日普希金在決鬥中受了重傷,29日死亡,萊蒙托夫得知消息後悲憤至極,寫下了《詩人之死》,激怒了沙皇。1837年2月18日萊蒙托夫 被捕,調任下諾夫哥羅德高加索騎兵團准尉,足跡遍佈舒沙、庫巴、舍馬哈、卡赫季。由於外祖母的奔走,1838年4月回到彼得堡。1840年生平唯一一部詩集發行。1840年2月,與法國公使之子巴蘭特發生衝突,萊蒙托夫朝天放了一槍,被交付軍事法庭。1840年4月,調往高加索現役軍隊田加騎兵團,第二次流放高加索。7月參與了高加索山民戰鬥和瓦列里克戰役。1841年2月初,返回彼得堡,其英勇事蹟備受肯定。1841年4月回到高加索。

1841年7月27日,在皮亞季戈爾斯克市近郊旁的馬舒克山麓,韋爾濟林的家庭晚會上,萊蒙托夫的玩笑激怒了士官生學校同學馬丁諾夫,虛榮心很強的馬丁諾夫要求決鬥。萊蒙托夫沒有開槍,結果馬丁諾夫一槍擊中了萊蒙托夫的心臟,當場身亡,年僅27歲。外祖母將其安葬在塔爾罕內。

米哈伊爾·尤列維奇·萊蒙托夫(俄語:Михаил Юрьевич Лермонтов;1814年10月15日-1841年7月27日),俄國作家、詩人。被視為普希金的後繼者。

生平

父親尤里·彼得羅維奇·萊蒙托夫是退役軍官,母親瑪利亞·米哈伊洛夫娜早逝,由外祖母家撫養長大,童年是在奔薩省阿爾謝尼耶娃的塔爾罕內莊園中度過,自幼體弱多病,能說流利的法語和德語。1827年全家搬到莫斯科,1828年進入莫斯科貴族寄宿中學,著手研究普希金和拜倫,開始從事寫詩創作,這時期的主要作品有《海盜》、《罪犯》、《奧列格》。1830年3月,莫斯科寄宿學校改為普通中學,萊蒙托夫請求退學,並前往斯托雷平家 族的謝列德尼科沃莊園,同年考入莫斯科大學。在友人A·M·韋列夏金娜的家中結識E·A·蘇什科娃,並與之熱戀。這時期開始抒情詩的創作,但他不斷地移情 別戀,又愛上了劇作家伊萬諾夫的女兒伊萬諾娃。1832年,前往聖彼得堡。同年11月通過近衛士官生入學考試。1835年,成為禁軍驃騎兵團騎兵少尉。 1837年1月27日普希金在決鬥中受了重傷,29日死亡,萊蒙托夫得知消息後悲憤至極,寫下了《詩人之死》,激怒了沙皇。1837年2月18日萊蒙托夫 被捕,調任下諾夫哥羅德高加索騎兵團准尉,足跡遍佈舒沙、庫巴、舍馬哈、卡赫季。由於外祖母的奔走,1838年4月回到彼得堡。1840年生平唯一一部詩集發行。1840年2月,與法國公使之子巴蘭特發生衝突,萊蒙托夫朝天放了一槍,被交付軍事法庭。1840年4月,調往高加索現役軍隊田加騎兵團,第二次流放高加索。7月參與了高加索山民戰鬥和瓦列里克戰役。1841年2月初,返回彼得堡,其英勇事蹟備受肯定。1841年4月回到高加索。

1841年7月27日,在皮亞季戈爾斯克市近郊旁的馬舒克山麓,韋爾濟林的家庭晚會上,萊蒙托夫的玩笑激怒了士官生學校同學馬丁諾夫,虛榮心很強的馬丁諾夫要求決鬥。萊蒙托夫沒有開槍,結果馬丁諾夫一槍擊中了萊蒙托夫的心臟,當場身亡,年僅27歲。外祖母將其安葬在塔爾罕內。

主要作品

- 抒情詩《鮑羅金諾》、《祖國》充滿了愛國感情,《孤帆》表達了對自由的渴望。

- 長詩《惡魔》抨擊了黑暗的農奴制社會。

- 《童僧》描寫了一個不願過監獄般修道院生活的少年山民的悲慘遭遇。

- 《商人卡拉雪梨科夫之歌》敘述蔑視沙皇權勢、敢於和沙皇衛兵決鬥的青年商人的悲劇。

- 中篇小說《當代英雄》,寫以畢巧林為代表的貴族知識分子在沙皇統治下精神空虛的生活。

- 劇本《假面舞會》反映上流社會的虛偽和欺詐。

Bibliography

- Spring, 1830, poem

- A Strange Man, 1831, drama/play

- The Masquerade, 1835, verse play

- Borodino, 1837, poem

- Death of the Poet, 1837, poem

- The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov, 1837, poem

- Sashka, 1839, poem

- The Novice, 1840, poem

- A Hero of Our Time (Герой нашего времени, 1840; 1842, 2nd edition; 1843, 3rd edition), novel

- Demon, 1841, poem

- The Princess of the Tide, 1841, ballad

- Valerik, 1841, poem

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (Russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов; IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjurʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲɛrməntəf]; October 15 [O.S. October 3] 1814 – July 27 [O.S. July 15] 1841), a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", became the most important Russian poet after Alexander Pushkin's death in 1837. Lermontov is considered the supreme poet of Russian literature alongside Pushkin and the greatest figure in Russian Romanticism. His influence on later Russian literature is still felt in modern times, not only through his poetry, but also through his prose, which founded the tradition of the Russian psychological novel.

Contents |

Early life

Lermontov was born in Moscow into a respectable noble family of the Tula Oblast, and grew up on the Tarkhany estate in the village of Tarkhany (now Lermontovo) in Penza Oblast. According to legend, his paternal family is descended from the Scottish Earls of Learmont, one of whom settled in Russia in the early 17th century, during the reign of Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. The legendary Scottish poet Thomas the Rhymer (Thomas Learmonth) is thus claimed as a relative of Lermontov. The only ascertainable genealogical information states that the poet was descended from Yuri (George) Learmont, a Scottish officer in the Polish service who settled in Russia in the middle of 17th century[1]Lermontov's father, Yuri Lermontov, like his father before him, was a military man. Having moved up the ranks to captain, he married the sixteen-year-old Maria Arsenyeva, to the great dismay of her mother, Yelizaveta Alekseyevna. A year after the marriage, on the night of October 3 (Old Style), 1814, Maria gave birth to Mikhail Lermontov. According to tradition, soon after his birth some discord between Lermontov's father and grandmother erupted, and unable to bear it, Maria fell ill and died in 1817. After her daughter's death, Yelizaveta Alekseyevna devoted all her love to her grandson, constantly afraid that his father might move away with him. Either because of this pampering or continuing family tension or both,the young Lermontov developed a fearful and arrogant temper, which he took out on the servants, and in vandalising his grandmother's garden.

As a small boy Lermontov listened to stories about the outlaws of the Volga region, about their great bravery and wild country life. When he was ten, Mikhail fell sick, and Yelizaveta Alekseyevna took him to the Caucasus because of its better climate. That was the beginning of his love for this region.

School years

The intellectual atmosphere in which he grew up was similar to that experienced by Pushkin, though the domination of French had begun to give way to a preference for English, and Lamartine shared popularity with Byron. In his early childhood Lermontov was educated by a Frenchman named Gendrot. Yelizaveta Alekseyevna felt that this was not sufficient and decided to take Lermontov to Moscow, to prepare for gymnasium. In Moscow, Lermontov was introduced to Goethe and Schiller by a German pedagogue, Levy, and shortly afterwards, in 1828, he entered the gymnasium. He proved to be an exceptional student. Also at the gymnasium he became acquainted with the poetry of Pushkin and Zhukovsky, and one of his friends, Katerina Khvostovaya, later described him as "married to a hefty volume of Byron". Katerina had at one time been the object of Lermontov's affections and to her he dedicated some of his earliest poems, "Нищий (У врат обители святой)" (The Beggar). At that time, along with his poetic passion, Lermontov also developed an inclination for poisonous wit and cruel, sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched by his ability to pin someone down with a well aimed epigram or nickname.At university

After the academic gymnasium, in August 1830 Lermontov entered Moscow University. That same summer the final, tragic act of the family discord played itself out. Deeply affected by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov left the Arseniev house for good, only to die a short time later. His father's death under such circumstances was a terrible loss for Mikhail and is reflected in his poems: "Forgive me, Will we Meet Again?" and "The Terrible Fate of Father and Son".Lermontov's career at the university was short-lived. He attended lectures faithfully, but he would often read a book in the corner of the auditorium, and rarely took part in student life. A prank pulled by a group of students against one of the professors named Malov brought his time at the University to an end.[clarification needed] Several biographers cite this incident as the reason for Mikhail's departure.[citation needed]

Young cadet - first poems

The events at the university led Lermontov to seriously reconsider his career choice. From 1830 to 1834 he attended the cadet school in Saint Petersburg and in due course he became an officer in the guards. At that time he began writing poetry. He also took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in the Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov, his long poem Borodino, poems addressed to the city of Moscow, and a series of popular ballads.Fame and exile

To express his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier wrote a passionate poem, Death of the Poet, — the latter part of which is explicitly addressed to the inner circles at the court, though not to the Tsar himself. The poem all but accuses the powerful "pillars" of Russian high society of complicity in Pushkin's death. Without mincing words, it portrays that society as a cabal of self-interested venomous wretches "huddling about the throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgment of God.The tsar Nicholas I, however, seems to have found more impertinence than inspiration in the address, as Lermontov was forthwith banished to the Caucasus as an officer in the dragoons.[2] He had been in the Caucasus with his grandmother as a boy of ten, and he felt himself at home, with emotions deeper than those of childhood recollection. The stern and gritty virtues of the mountain tribesmen against whom he had to fight, no less than the scenery of the rocks and of the mountains themselves, were close to his heart; the tsar had exiled him to his spiritual homeland.

Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in 1838 and 1839, and his indignant observations of the aristocratic milieu, where fashionable ladies welcomed him as a celebrity, occasioned his play Masquerade. His doomed love for Barbara Lopukhina was recorded in the novel Princess Ligovskaya, which he never finished. Lermontov's duel with a son of the French ambassador led to him being returned to the army fighting the war in the Caucasus, where he distinguished himself in hand-to-hand combat at the Battle of the Valerik River, the basis for his poem Valerik.

Death

On July 25, 1841, at Pyatigorsk, fellow army officer Nikolai Martynov, who felt offended by one of Lermontov's jokes, challenged him to a duel. The duel took place two days later at the foot of Mashuk mountain. Lermontov was killed by Martynov's first shot. Several of his verses were discovered posthumously in his notebook. He is buried at Tarkhany.Works

Lermontov's poetic development was unusual. His earliest unpublished poems that he circulated in manuscript through his friends in the military were pornographic in the extreme, with elements of sadism. His subsequent reputation was clouded by this, so much so that admission of familiarity with Lermontov's poetry was not permissible for any young upper-class woman for a good part of the 19th century. These poems were published only once, in 1936, as part of a scholarly edition of Lermontov's complete works (edited by Irakly Andronikov).

---

Russian writer Maxim Gorky died on June 18th 1936. A keen Marxist—but critical of Lenin's undemocratic means—he was exiled from Russia, only to return under Stalin as a leading writer of the socialist realism movement

高爾基(Gorky, Maxim or Maksim / Максим Горький)(公元1868.3.28—1936.6.18)

俄國作家。小學中輟生,輾轉做過各種勞力工作。社會主義現實派的創始者。代表作包括小說《母親》以及話劇《底層》。《我的大學》(· My Universities (Мои университеты), Autobiography Part III, 1923 原作,1922-23,北京:人民文學,1956。我採用1992年新版第11刷,沒有譯者名字和資訊。出版過《高爾基文集》 16卷。)是自傳體小說三部曲的最後一部,另兩部為·《童年》 My Childhood (Детство), Autobiography Part I, 1913–1914 /《在人間》In the World (В людях), Autobiography Part II, 1916

《不合時宜的思想》南京:江蘇人民, 1998。

Wikipedia 的 以英文版English最好

日文版的作品都是1910年前的

作品

- マカル・チュドラ(1892年)

- チェルカシュ(1895年)

- フォマ・ゴルデーエフ(1899年)

- 母(1907年)

- どん底(1902年)

- 海燕の歌(1901年)

中文

如上 說不定高爾基全集已齊 可是此篇內容貧乏

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。