纽约客闲话之随感录:敢于破禁的出版家- 随笔- 文心作品- 文心社 ...

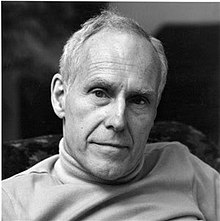

Barney Rosset

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Barnet Lee Rosset, Jr.

May 28, 1922 |

| Died | February 21, 2012 (aged 89) |

| Occupation | Book, magazine publisher |

| Spouse(s) | Joan Mitchell, Hannelore Eckert, Cristina Agnini, Lisa Krug, Astrid Myers |

| Children | Peter, Tansey, Beckett, Chantal |

Barnet Lee "Barney" Rosset, Jr. (May 28, 1922 – February 21, 2012) was the owner of the publishing house Grove Press, and publisher and editor-in-chief of the magazine Evergreen Review. He led a successful legal battle to publish the uncensored version of D. H. Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover, and later was the American publisher of Henry Miller's controversial novel Tropic of Cancer. The right to publish and distribute Miller's novel in the United States was affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1964, in a landmark ruling for free speech and the First Amendment.

Contents

Early life[edit]

Rosset was born and raised in Chicago to a Jewish father, Barnet Rosset, and an Irish Catholic mother, Mary (née Tansey).[1][2][3] He attended the progressive Francis Parker School,[4] where he was best friends with renowned cinematographer Haskell Wexler. Rosset also said that Robert Morss Lovett, the grandfather of Rosset's high school sweetheart, and professor of English at the University of Chicago had been a great influence on him.[4]

Rosset attended Swarthmore College for one year and then enlisted in the army in 1942. It was at Swarthmore that Rosset discovered the work of Henry Miller.

Career[edit]

During World War II, he served in the Army Signal Corps as an officer in a photographic company stationed in Kunming, China.[4] In 2002, Rosset exhibited a collection of his War Photographs from his time in China in a New York Gallery. The exhibit included graphic photos of wounded and dead Chiang Kai-shek soldiers.[4]...

Grove Press and Evergreen Review writers[edit]

Rosset introduced American readers to numerous significant writers, including Samuel Beckett (Nobel Prize in Literature 1969), Pablo Neruda (Nobel Prize 1971), Octavio Paz (Nobel Prize 1990), Kenzaburō Ōe (Nobel Prize 1994), Harold Pinter (Nobel Prize 2005), Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, Khushwant Singh, Jean Genet, John Rechy, Kathy Acker, Eugène Ionesco and Tom Stoppard.

Interviewed by Tin House publisher Win McCormack, Rosset talked about publishing Beckett:

- I had actually read a little bit of Beckett in transition Magazine and a couple of other places. I was going to the New School. My New School life and the beginnings of Grove crossed over. At the New School, I had professors like Wallace Fowlie, Alfred Kazin, Stanley Kunitz and others, who were very, very important to me. I was doing a great deal of reading and writing papers for them, and one day I read in The New York Times about a play called Waiting for Godot that was going on in Paris. It was a small clip, but it made me very interested. I got hold of it and read it in the French edition. It had something to say to me. Oddly enough, it had a sense of desolation, like Miller, though in its language, its lack of verbiage, it was the opposite of Miller. Still, the sense of a very contemporary lost soul was compelling. I got Wallace Fowlie to read it. His specialty was French literature. His judgment meant a lot to me even though he was so different from me. He was a convert to Catholicism, he was gay, and incredibly intelligent. He read the play and told me that he thought - and this before anybody had really heard about it much - that it would be one of the most important works of the 20th Century. And Sylvia Beach got involved in it somehow. She was a friend and admirer of Beckett. Waiting for Godot just hit something in me. I got what Beckett writing was available and published it. He flew into the web and got trapped. He had been turned down by Simon and Schuster, I found out, much earlier, on an earlier novel.[6]

In an interview with the Brooklyn Rail, Rosset spoke about the Henry Miller's Tropic of Capricorn being taken to court for obscenity charges:

- We had a case in New York and, of course, he [Miller] wouldn't go to the court. I had lunch with him at a restaurant on sixth Avenue right near here called Alfred's with our lawyer and three or four other people, and then we had to go to court. But he wouldn't go. He'd been summonsed so he was breaking the law by not going. So we went into court, and the District Attorney questioned me and said, "You see that we have a jury here of men and women with children who go to school right near where that book is on sale, near the subway stop. What'd you think they feel to have their children reading this book?" So I took out the book and started reading and the jury started laughing and they thought it was wonderful. I said to them, "If your children got this book and read the whole book you ought to congratulate them." And they loved it, and they refused to convict me of anything. That was a great pleasure. Miller couldn't leave this country until the decision was in, verified and so forth. For at least a year or two years, he couldn't go. It was so funny because they accused me of soliciting him to write the book—write Tropic of Cancer and Capricorn—in Brooklyn, and at that point I was only 8 years old! Miller was a little older than me. It was a specific charge against me that was absurd. I was a pimp supposedly. They didn't even bother to see how ridiculous their charge would look.[7]

Launched in 1957, Evergreen Review pushed the limits of censorship, inspiring hundreds of thousands of younger Americans[citation needed] to embrace the counterculture. Grove Press published Beat Generation writers, including William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, John Rechy, Hubert Selby, Jr. and Jack Kerouac. Rosset also purchased the American distribution rights to the Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow).

The online Evergreen Review features Beat classics as well as debuts of contemporary writers.[8] In 2007, Rosset married Astrid Myers, then-managing editor of the online Evergreen Review. In 2008, Rosset completed writing his autobiography (now published as Rosset: My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship.[9] He died in 2012 after a double heart valve replacement.[10]

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。