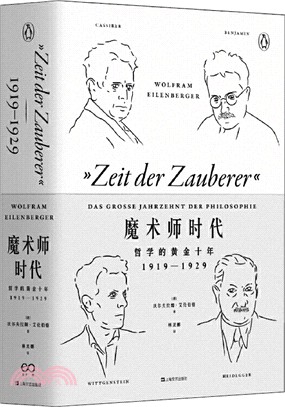

Time of the Magicians

Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy

By Wolfram Eilenberger

Translated by Shaun Whiteside

Illustrated. 418 pages. Penguin Press. $30.

BOOKS OF THE TIMES

How Wittgenstein and Other Thinkers Dealt With a Decade of Crisis

By Jennifer Szalai

Aug. 14, 2020

In the autumn of 1922, as Germany was convulsed by food shortages and soaring inflation, the philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote a letter to his wife about the intricate choreography required to secure the most basic needs. “Mother asks if they should send potatoes even before 1 Oct; I answered yes and sent the money at the same time,” he explained. “What should I do when the potatoes arrive?”

At a time of crisis, the threats to existence can be so immediate that most people become understandably preoccupied with urgent matters of survival. But even as Heidegger was worried about the potatoes, he believed that a crisis could also offer a radical break from the dispensation that produced it, a moment of genuine openness, a chance to rethink everything anew.

As Wolfram Eilenberger writes in “Time of the Magicians,” his vibrant group portrait of four philosophers during a turbulent decade, Heidegger welcomed danger and suffering as a social condition that forced people to confront their mortality — at least, that was the idea. His wife wanted to ensure that the demands of reality didn’t intrude too much on his work, so she planned and supervised the construction of a cabin in the Black Forest, financing it with her inheritance. There, Martin could live like a sturdy peasant, taking in the mountain air and spending days on his woodwork before contemplating an existence that was grounded in groundlessness.

Heidegger finally had what Eilenberger calls “a hut of one’s own.” The irreverence is funny, but it amounts to more than just a joke; everything in “Time of the Magicians” — ideas, narrative and phrasing (translated from the German into seamless English by Shaun Whiteside) — has been fused into a readable, resonant whole.

Ernst Cassirer, the most settled and least eccentric of the bunch, painstakingly built a reputation for lucid explication and formidable erudition, not for charisma or audacity. “Cassirer’s only truly radical trait was his will to equilibrium,” Eilenberger writes. To his younger detractors, the white-haired Cassirer was the establishment personified. A photograph in the book has him wearing a ruff.

Image

Wolfram Eilenberger, author of “Time of the Magicians.”Credit...Annette Hauschild

But Cassirer was responding to the same crisis that animated the other three of Eilenberger’s magicians — a sense that the old ways of philosophizing had failed to keep up with the reality of lived experience. The dominant Kantian approach was born during the era of Newtonian physics, which was displaced in 1905 by Einstein’s theory of relativity. Freud had unsettled any assumptions about the transparency of human consciousness. An Enlightenment faith in progress was laid to waste by the mechanized carnage of World War I. Eilenberger quotes Max Scheler, another German philosopher, who put it this way: “Ours is the first period when man has become completely and totally problematical to himself, when he no longer knows what he is, but at the same time knows that he knows nothing.”

Language was implicated in this plight, and the responses among the figures in this book were varied and often strange. Heidegger insisted on a vocabulary of Dasein (“being there”) and Sein-zum-Tode (“being-toward-death”), neologisms that weren’t tainted by the old ways of thinking. Wittgenstein drew a distinction between meaningful propositions and those that only seemed meaningful, famously ending the “Tractatus” with an aphorism: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.” A chaotic, euphoric Benjamin (wonderfully described in this book as a “one-man Weimar”) thought that “overnaming” led to “melancholy,” and that language was better suited for “the revelation of being.”

Cassirer’s understanding of language was capacious, incorporating not only German and English but also myth, religion, technology and art. Different languages offered different ways of seeing the world. His pluralistic outlook seemed to provide him with an escape valve. As he wrote to his wife, “I can express everything I need without difficulty.”

As the most stolid figure in Eilenberger’s book, Cassirer is also, somewhat perversely, the most enigmatic. Compared with the others’ sexual adventuring (Benjamin, Heidegger) or sexual anguish (Wittgenstein), Cassirer’s love life was uneventful and untroubled, leading Eilenberger to suggest that the Cassirers’ resolutely bourgeois marriage “acquired a distinctively political edge as a rejection of confused adventures, revolutions or civil wars.” As it happened, Cassirer was the only one of the four to speak up publicly for the embattled Weimar Republic. He was also the only democrat.

In 1929, a debate between Cassirer and Heidegger amid the snowy peaks of Davos clarified the stakes: Reject your distracting anxiety, per Cassirer, and embrace the liberation offered by culture; or reject your distracting culture, per Heidegger, and embrace the liberation offered by your anxiety. But the reality for attendees was more mundane. One journalist described a self-congratulatory atmosphere where the audience “enjoyed the spectacle of a very nice person and a very violent person, who was still trying terribly hard to be nice, delivering monologues.”

Eilenberger is a terrific storyteller, unearthing vivid details that show how the philosophies of these men weren’t the arid products of abstract speculation but vitally connected to their temperaments and experiences. Yet he also points out that as much as they were wrestling with life-and-death philosophical questions, the bigger crisis was still to come.

By May 1933, Heidegger would be a member of the Nazi Party, and Cassirer, an assimilated Jew, would leave Germany forever, eventually settling in the United States. Cassirer’s unwavering decency made him a stalwart defender of Weimar’s democratic ideals, but it had also kept him imperturbable and optimistic until it was almost too late.

“When we first heard of the political myths we found them so absurd and incongruous, so fantastic and ludicrous that we could hardly be prevailed upon to take them seriously,” Cassirer would later write, before his death in 1945. “By now it has become clear to all of us that this was a great mistake.”

***

A grand narrative of the intertwining lives of Walter Benjamin, Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Ernst Cassirer, major philosophers whose ideas shaped the twentieth century

The year is 1919. The horror of the First World War is still fresh for the protagonists of Time of the Magicians, each of whom finds himself at a crucial juncture. Walter Benjamin, having survived the flu during the 1918 pandemic, is trying to flee his overbearing father and floundering in his academic career. Ludwig Wittgenstein, by contrast, has dramatically decided to divest himself of the monumental fortune he stands to inherit as a scion of one of the wealthiest industrial families in Europe, in search of absolute spiritual clarity. Meanwhile, Martin Heidegger, having managed to avoid combat in war by serving instead as a meteorologist, is carefully cultivating his career. Finally, Ernst Cassirer is working furiously in academia, applying himself intensely to his writing and the possibility of a career at Hamburg University. The stage is set for a great intellectual drama, which will unfold across the next decade. The lives and ideas of this extraordinary philosophical quartet will converge as they become world historical figures. But with the Second World War looming on the horizon, their fates will be very different.

Wolfram Eilenberger stylishly traces the paths of these remarkable and turbulent lives, which feature not only philosophy but some of the most important other figures of the century, including John Maynard Keynes, Hannah Arendt, and Bertrand Russell. In doing so, he tells a gripping story about four of history's most ambitious and passionate thinkers, and illuminates with rare clarity and economy their brilliant ideas, which all too often have been regarded as enigmatic or opaque.

Wolfram Eilenberger

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy (英語) , 2020/8/18

Wolfram Eilenberger (著)

魔術師時代:哲學的黃金十年(1919-1929)(簡體書)

- 系列名:藝文志·企鵝叢書

- ISBN13:9787532172979

- 出版社:上海文藝出版社

- 作者:(德)沃爾夫拉姆‧艾倫伯格

- 譯者:林靈娜;王曉豐

- 裝訂/頁數:平裝/446頁

- 規格:21cm*14.5cm (高/寬)

- 版次:一版

- 出版日:2019/

馬丁·海德格爾的事業平步青雲,並邂逅了與漢娜·阿倫特的愛情。跌跌撞撞的瓦爾特·本雅明在卡普裡島瘋狂迷戀上了一個來自拉脫維亞的無政府主義者,也正是這 段愛戀使他自己成為了一名革命者。天才維特根斯坦是億萬富翁之子,他在劍橋被譽為哲學的上帝,而這樣的天之驕子卻來到了上奧地利州偏遠地區擔任鄉村小學教師,過著完全赤貧的生活。最後還有恩斯特·卡西爾,他在遷居到漢堡中產階級區的幾年前,親身經歷了正在抬頭的反猶主義。

本書除梳理了海德格爾、本雅明、維特根斯坦和卡西爾在1919-1929年間的各異的日常生活、情感經歷和思想狀況,還力求將四位哲人的思想予以對觀,展現了他們在面臨時代根本問題時各自的回答和應對方式。借助作者出色的敘述,我們在這四位卓越哲學家的生活道路和革命性思想中,看到了當今世界的根源。回望20世紀20年代,既是感悟又是警醒。

第二章 跳躍 1919

第三章 語言 1919-1920

第四章 構形 1922-1923

第五章 你 1923-1925

第六章 自由 1925-1927

第七章 拱廊街 1926-1928

第八章 時間 1929

結語

著作目錄

參考文獻摘選

後記

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。