The British Library

Today is the 210th anniversary of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, which was first published in 1813.

The novel introduced us to a cast of memorable characters, from the witty Elizabeth Bennet to the aloof Mr Darcy. Who’s your favourite character from the book?

If you love this classic story, you can help us continue to care for it (and many others) by adopting a book in our collection.

Find out more http://bit.ly/3Y3yVgN

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Illustrator Charles Edmund Brock

Illustrator Charles Edmund Brock 012621.h.17

012621.h.17Charles Edmund Brock (5 February 1870 – 28 February 1938) was a widely published English painter, line artist and book illustrator, who signed most of his work C. E. Brock. He was the eldest of four artist brothers, including Henry Matthew Brock, also an illustrator.

Early life[edit]

Brock was born on 5 February 1870 in Holloway, London. The family later settled in Cambridge. He studied art briefly under sculptor Henry Wiles.[1]

Name confusion[edit]

Charles Edmund Brock RI of Cambridge was sometimes confused with the unrelated Charles Edmond Brock RI (1882 – 1952) of London,[2][note 1][3] a portrait painter who painted member of the Royal Family[4] and the aristocracy, and was the son of English Sculptor Thomas Brock RA (1 March 1847 – 22 August 1922).

The confusion was so great that they even found themselves paying each other's bills. They solved by agreeing that Charles Edmund of Cambridge would stop using Edmund and that Charles Edmond of London would stop using Charles.[5] In Graves' Dictionary of Contributors to the Royal Academy he lists the Cambridge Brock as Charles E. Brock - Painter, and the London Brock as C. Edmond Brock - Painter.[6]

This was not the only confusion. One report of a Cambridge Council meeting attributed the Victoria Memorial to C. E. Brock. The name of the sculptor to which the commission for a bust of Queen Victoria is entrusted is Mr. Thomas Brock, R.A., and not, of course, Mr. C. E, Brock, stated by a mistake which crept into our report of the meeting last week.[7]

Work[edit]

Brock received his first book commission at the age of 20 in 1890. He became very successful, and illustrated books for authors such as Jonathan Swift, William Thackeray, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and George Eliot. Brock also contributed pieces to several magazines such as The Quiver, The Strand, and Pearsons.[8] He used the Cambridge college libraries for his "picture research."[8] In illustration Brock is best known for his line work, initially working in the tradition of Hugh Thomson, but he was also a skilled colourist. As a painter he received plaudits for his realism and vibrancy he created in his work. Only a small quantity of his paintings have been located which is why their prices have been so high.

Brock and his brothers maintained a Cambridge studio filled with various curios, antiques, furniture, and a costume collection. They owned a large collection of Regency era costume prints and fashion plates, and had clothes specially made as examples for certain costumes.[8] Using these, family members modeled for each other.

Unequivocally the most famous and valuable paintings in Brock's career were his golf paintings – The Bunker; The Drive; and The Putt – all of which were painted in 1894 as part of the same series. These paintings were acquired together by a Japanese collector in 1991 for $1.5 million.[9] The most valuable of these is The Putt, which was repainted due to the position of the caddy and bystander as the commissioner of the painting wanted to bring himself, the putter, more into the forefront of the painting. The initial unsigned painting is considered to be the more impressive of the two versions, and is even used as the print for postcards and posters sold in many golf museums.

| Year | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1910 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 29 | 28 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 108 |

| Notes | [note 2] | [note 3] | [note 4] | [note 5] | [note 6] |

Brock published 109 illustrations[note 7] in Punch between 6 February 1901 and 30 March 1910. He output in Punch tapered off after 1905 and he did not publish any more work in Punch after 1910.[10] Brock continued to work on book illustration and on portraits. Some of the portraits by Brock in national collections date from the 1920. He continued to illustrate books right up until hid death, with Gunby Hadath's Pamela: A Story for Girls (1938)[note 8] being one of the last books he illustrated. Books he was working on at the time of his death were completed by other illustrators. Brock was one of the twenty leading illustrators selected by Percy Bradshaw for a portfolio in his 1917/1918 The Art of the Illustrator.[note 9]

Brock was an occasional exhibitor at various venues.[note 10] He died on 28 February 1938 in Cambridge.[14]

Style[edit]

The approach of C.E. Brock's work varied with the sort of story he was illustrating. Some was refined and described as "sensitive to the delicate, teacup-and-saucer primness and feminine outlook of the early Victorian novelists," while other work was "appreciative of the healthy, boisterous, thoroughly English characters" – soldiers, rustics, and "horsey types."[15] Other illustrations were grotesqueries drawn to amuse children looking at or reading storybooks.

Assessment[edit]

Joseph Pennell in his Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtmanship . . . made the following assessment of Brock at the very start of his career as an illustrator: Mr. Brock has come out with "Hood’s Humorous Poems". His drawing can scarce be called original, — there are many reminiscences in it, — but his humour, dramatic action, and his arrangement are quite his own. H is sense of illustration is good, and is well shown in the concentration on the black horse and black cap of the huntsman in the title; possibly this is exaggerated, but it is a good sort of exaggeration. In the other drawing, " The Supper Superstition", the story is extremely well told with movement and go. There are several other drawings in the book quite as good; enough of them to prove that Mr. Brock has something to say for himself, besides showing how well he has studied other people.[16]

Examples of complete book illustrations[edit]

The following examples show what a complete set of illustrations for a single book look like.

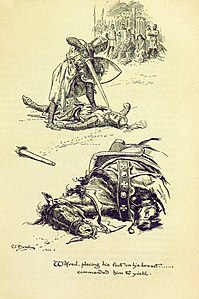

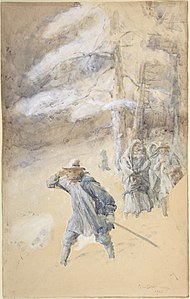

An adventure novel[edit]

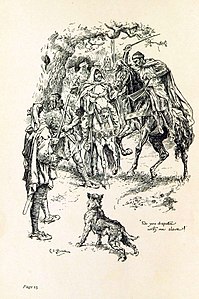

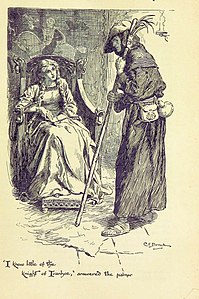

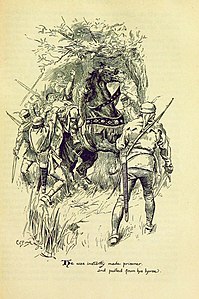

Brock illustrated a new edition of Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe for Service & Paton in 1897. The new edition had 16 full page illustrations. New illustrations were one of the ways in which publishers tried to sell titles were had already had a number of editions. The illustrations are by courtesy of The British Library the whole book is available on-line. The illustrations for Ivanhoe would have benefited from the props that the Brock's kept in their studio to serve as examples for arms, clothing, and so on.

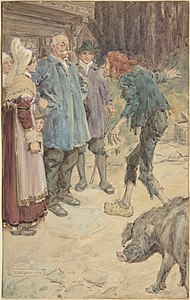

A book for children[edit]

Lucas Malet was the pseudonym of Mary St Leger Kingsley (4 June 1852 – 27 October 1931), a Victorian novelist. Although most of here output was for adults, she did produce some juvenile fiction In 1887, Kegan Paul & Co.[note 11] published Malet's short[note 12] book Little Peter: A Christmas Morality for Children of any Age with nine full page illustrations including the frontispiece, and several smaller ones, by Paul Hardy.[note 13] The book tells the story of a small boy who befriends a very ugly and socially-despised man, who saves him in the end. The story was apparently popular as it was reprinted numerous times, most recently in 2010. In 1909, Henry Frowde and Hodder & Stoughton's joint venture reissued the book, but this time with eight full-page colour illustrations, including the frontispiece, by Charles Brock. The costs of colour illustration had decreased significantly since the 1887 edition, and colour was now the norm for books for younger children. This was good news for an artist as versatile as Brock, as it increased the options for selling his work. The following illustrations show the story in outline.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。