列王紀選 張鴻年譯,人民文學,1991

Ferdowsi's Shahnameh : The Book of Kings". 列王紀選,Rostam,The tragedy of Sohrab

SShahnameh Ferdowsi's Shahnameh : The Book of Kings". 列王紀選,Rostam,The tragedy of Sohrab

Shahnameh (Book of Kings) Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020)

The Shahnameh, also transliterated as Shahnama (Persian: شاهنامه pronounced , "The Book of Kings"), is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (two-line verses),[1] the Shahnameh is the world's longest epic poem written by a single poet. It tells mainly the mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Arab conquest of Iran in the 7th century. Modern Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan and the greater region influenced by the Persian culture (such as Georgia, Armenia, Turkey and Dagestan) celebrate this national epic.

The work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of Iran.[2] It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion and the death of the last Sassanid ruler of Persia during the Muslim conquest which brought an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

بسی رنج بردم در این سال سی؛ عجم زنده کردم بدین پارسی

|

I have struggled much these thirty years in order to keep Persian ajam (meaning non-Arabic, or specifically Iranian).

|

Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyath al-Din Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai Khosrow, Kay Kāvus, and Kai Kobad; and that Ala' al-Din Kai-Qubad I had some passages from the Shahname inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact (i.e. the importance of Persian influence) is undeniable.[16]

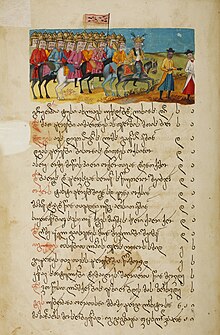

On Georgian identityDuring the ten centuries passed after Firdausi composed his monumental work, heroic legends and stories of Shahnameh have remained the main source of the storytelling for the peoples of this region: Persians, Pashtuns, Kurds, Gurans, Talishis, Armenians, Georgians, North Caucasian peoples, etc.[19]

The Šāh-nāma was translated, not only to satisfy the literary and aesthetic needs of readers and listeners, but also to inspire the young with the spirit of heroism and Georgian patriotism. Georgian ideology, customs, and worldview often informed these translations because they were oriented toward Georgian poetic culture. Conversely, Georgians consider these translations works of their native literature. Georgian versions of the Šāh-nāma are quite popular, and the stories of Rostam and Sohrāb, or Bījan and Maniža became part of Georgian folklore.[20]

On Turkic identityDistinguished scholars of Persian such as Gvakharia and Todua are well aware that the inspiration derived from the Persian classics of the ninth to the twelfth centuries produced a ‘cultural synthesis’ which saw, in the earliest stages of written secular literature in Georgia, the resumption of literary contacts with Iran, “much stronger than before” (Gvakharia, 2001, p. 481). Ferdowsi’s Shahnama was a never-ending source of inspiration, not only for high literature, but for folklore as well. “Almost every page of Georgian literary works and chronicles [...] contains names of Iranian heroes borrowed from the Shahnama” (ibid). Ferdowsi, together with Nezāmi, may have left the most enduring imprint on Georgian literature (...)[21]

I've reached the end of this great history And all the land will talk of me: I shall not die, these seeds I've sown will save My name and reputation from the grave, And men of sense and wisdom will proclaim When I have gone, my praises and my fame.[28]

Much I have suffered in these thirty years, I have revived the Ajam with my verse. I will not die then alive in the world, For I have spread the seed of the word. Whoever has sense, path and faith, After my death will send me praise.[29]

BiographiesWhen we turn our attention to a peaceful, civilized people, the Persians, we must—since it was actually their poetry that inspired this work—go back to the earliest period to be able to understand more recent times. It will always seem strange to the historians that no matter how many times a country has been conquered, subjugated and even destroyed by enemies, there is always a certain national core preserved in its character, and before you know it, there re-emerges a long-familiar native phenomenon. In this sense, it would be pleasant to learn about the most ancient Persians and quickly follow them up to the present day at an all the more free and steady pace.[31]

- Chahar Maqaleh ("Four Articles") by Nezami 'Arudi-i Samarqandi

- Tazkeret Al-Shu'ara ("The Biography of poets") by Dowlat Shah-i Samarqandi

- Baharestan ("Abode of Spring") by Jami

- Lubab ul-Albab by Mohammad 'Awfi

- Natayej al-Afkar by Mowlana Muhammad Qudrat Allah

- Arafat Al-'Ashighin by Taqqi Al-Din 'Awhadi Balyani

- Anvari remarked about the eloquence of the Shahnameh, "He was not just a Teacher and we his students. He was like a God and we are his slaves".[33]

- Asadi Tusi was born in the same city as Ferdowsi. His Garshaspnama was inspired by the Shahnameh as he attests in the introduction. He praises Ferdowsi in the introduction[34] and considers Ferdowsi the greatest poet of his time.[35]

- Masud Sa'ad Salman showed the influence of the Shahnameh only 80 years after its composition by reciting its poems in the Ghaznavid court of India.

- Othman Mokhtari, another poet at the Ghaznavid court of India, remarked, "Alive is Rustam through the epic of Ferdowsi, else there would not be a trace of him in this World".[36]

- Sanai believed that the foundation of poetry was really established by Ferdowsi.[37]

- Nizami Ganjavi was influenced greatly by Ferdowsi and three of his five "treasures" had to do with pre-Islamic Persia. His Khosro-o-Shirin, Haft Peykar and Eskandar-nameh used the Shahnameh as a major source. Nizami remarks that Ferdowsi is "the wise sage of Tus" who beautified and decorated words like a new bride.[38]

- Khaghani, the court poet of the Shirvanshah, wrote of Ferdowsi:"The candle of the wise in this darkness of sorrow,The pure words of Ferdowsi of the Tusi are such,His pure sense is an angelic birth,Angelic born is anyone who's like Ferdowsi."[39]

- Attar wrote about the poetry of Ferdowsi: "Open eyes and through the sweet poetry see the heavenly eden of Ferdowsi."[40]

- In a famous poem, Sa'adi wrote:"How sweetly has conveyed the pure-natured Ferdowsi,May blessing be upon his pure resting place,Do not harass the ant that's dragging a seed,because it has life and sweet life is dear."[41]

- In the Baharestan, Jami wrote, "He came from Tus and his excellence, renown and perfection are well known. Yes, what need is there of the panegyrics of others to that man who has composed verses as those of the Shah-nameh?"

The tragedy of Sohrab

Rostam was unaware that he had a son, Sohrab, by Princess Tahmina. He had not seen the Princess for many years. After years without any real knowledge of one another, Rostam and Sohrab faced each other in battle, fighting on opposing sides. Rostam did not recognise his own son, although Sohrab had suspicions that Rostam may be his father.

They fought in single combat and Rostam wrestled Sohrab to the ground, stabbing him fatally. As he lay dying, Sohrab recalled how his love for his father – the mighty Rostam - had brought him there in the first place. Rostam, to his horror, realised the truth. He saw his own arm bracelet on Sohrab, which he had given to Tahmina many years before and which Tahmina had given to Sohrab before the battle, in the hope that it might protect him.

But he realised the truth too late. He had killed his own son, ‘the person who was dearer to him than all others’. This is one of the most tragic episodes of the Shahname.

- The unknown writer of the Tarikh Sistan ("History of Sistan") written around 1053

- The unknown writer of Majmal al-Tawarikh wa Al-Qasas (c. 1126)

- Mohammad Ali Ravandi, the writer of the Rahat al-Sodur wa Ayat al-Sorur (c. 1206)

- Ibn Bibi, the writer of the history book, Al-Awamir al-'Alaiyah, written during the era of 'Ala ad-din KayGhobad

- Ibn Esfandyar, the writer of the Tarikh-e Tabarestan

- Muhammad Juwayni, the early historian of the Mongol era in the Tarikh-e Jahan Gushay (Ilkhanid era)

- Hamdollah Mostowfi Qazwini also paid much attention to the Shahnameh and wrote the Zafarnamah based on the same style in the Ilkhanid era

- Hafez-e Abru (1430) in the Majma' al-Tawarikh

- Khwand Mir in the Habab al-Siyar (c. 1523) praised Ferdowsi and gave an extensive biography on Ferdowsi

- The Arab historian Ibn Athir remarks in his book, Al-Kamil, that, "If we name it the Quran of 'Ajam, we have not said something in vain. If a poet writes poetry and the poems have many verses, or if someone writes many compositions, it will always be the case that some of their writings might not be excellent. But in the case of Shahnameh, despite having more than 40 thousand couplets, all its verses are excellent."[42]

- In a 1971–1976, Tajikfilm trilogy comprising Skazanie o Rustame[1], Rustam i Sukhrab[2] and Skazanie o Sijavushe[3].

- Bangladesh has made a blockbuster film, Shourab Rustom, in 1993.

- A Bollywood film, Rustom Sohrab [4], based on the story of Rustam and Sohrab, was made in 1963 and starred Prithviraj Kapoor.

- Persian TV series Chehel Sarbaz (Forty Soldiers), released on 2007, directed by Mohammad Nourizad, concurrently tells the story of Rostam and Esfandiar, biography of Ferdowsi, and a few other historical events.[70]

- Persian short animation Zal & Simorgh, 1977, directed by Ali Akbar Sadeghi, narrates the story of Zal from birth until returning to the human society.

- The Legend of Mardoush (2005), a long animated Persian trilogy, tells the mythical stories of Shahnameh from the kingdom of Jamshid to the victory of Fereydun over Zahhak.

- The Last Fiction (2017), a long animated movie, has an open interpretation of the story of Zahhak.[71] The movie is preceded by the graphic novels Jamshid Dawn 1 & 2 (created by the same team) whose aim is to familiarize adolescents and youth with the myth of Jamshid.

- List of Shahnameh characters

- Rostam and Sohrab, an opera by Loris Tjeknavorian

- Sohrab and Rustum, an 1853 poem by Matthew Arnold

- Naqqāli, a performing art based on Shahnameh

- Vis and Rāmin, an epic poem similar to the Shahnameh

- Shahrokh Meskoob

- Mir Jalaleddin Kazzazi

- Lalani, Farah (13 May 2010). "A thousand years of Firdawsi's Shahnama is celebrated". The Ismaili. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- Ashraf, Ahmad (30 March 2012). "Iranian Identity iii. Medieval Islamic Period". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved April 2010.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, Djalal (26 January 2012). "Ferdowsi, Abu'l Qāsem i. Life". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

the poet refers... to the date of the Šāh-nāma’s completion as the day of Ard (i.e., 25th) of Esfand in the year 378 Š. (400 Lunar)/8 March 1010

- Zaehner, Robert Charles (1955). Zurvan: a Zoroastrian Dilemma. Biblo and Tannen. p. 10. ISBN 0819602809.

- "A possible predecessor to the Khvatay-Namak could be the Chihrdad, one of the destroyed books of the Avesta (known to us because of its listing and description in the Middle Persian Zoroastrian text, the Dinkard 8.13)." K.E. Eduljee, Zoroastrian Heritage, "Ferdowsi's Shahnameh," http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/shahnameh/

- Safa, Zabihollah (2000). Hamase-sarâ’i dar Iran, Tehran 1945.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1991). Ferdowsī: A Critical Biography. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publishers. p. 49. ISBN 0939214830.

- Khatibi, Abolfazl (1384/2005). Anti-Arab verses in the Shahnameh. 21, 3, Autumn 1384/2005: Nashr Danesh.

- Katouzian, Homa (2013). Iran: Politics, History and Literature. Oxon: Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 9780415636896.

- Mutlaq, Jalal Khaleqi (1993). "Iran Garai dar Shahnameh" [Iran-centrism in the Shahnameh]. Hasti Magazine. Tehran: Bahman Publishers. 4.

- Ansari, Ali (2012). The Politics of Nationalism in Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780521867627.

- Fischer, Michael (2004). Mute Dreams, Blind Owls, and Dispersed Knowledges: Persian Poesis in the Transnational Circuitry. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780822385516.

- "Ferdowsi's "Shahnameh": The Book of Kings". The Economist. 16 September 2010.

- Perry, John (23 June 2010). "Šāh-nāma v. Arabic Words". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Seyed-Gohrab, Ali Ashgar (2003). Laylī and Majnūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Niẓāmī's Epic Romance. Leiden: Brill. p. 276. ISBN 9004129421.

- Köprülü, Mehmed Fuad (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Translated by Gary Leiser and Robert Dankoff. London: Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 0415366860.

- Dickson, M.B.; and Welch, S.C. (1981). The Houghton Shahnameh. Volume I. Cambridge, MA and London. p. 34.

- Savory, R. M. "Safavids". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.).

- Arakelova, Victoria. "Shahnameh in the Kurdish and Armenian Oral Tradition (abridged)" (PDF). Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Giunshvili, Jamshid Sh. (15 June 2005). "Šāh-nāma Translations ii. Into Georgian". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Farmanfarmaian 2009, p. 24.

- Bosworth, C.E. "Barbarian Incursions: The Coming of the Turks into the Islamic World". In Islamic Civilization, ed. D.S. Richards. Oxford, 1973. p. 2. "Firdawsi's Turan are, of course, really Indo-European nomads of Eurasian Steppes... Hence as Kowalski has pointed out, a Turkologist seeking for information in the Shahnama on the primitive culture of the Turks would definitely be disappointed. "

- Bosworth, C.E. "The Appearance of the Arabs in Central Asia under the Umayyads and the Establishment of Islam". In History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting, ed. M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth. Multiple History Series. Paris: Motilal Banarsidass Publ./UNESCO Publishing, 1999. p. 23. "Central Asia in the early seventh century, was ethnically, still largely an Iranian land whose people used various Middle Iranian languages."

- Frye, Richard N. (1963). The Heritage of Persia: The Pre-Islamic History of One of the World's Great Civilizations. New York: World Publishing Company. pp. 40–41.

- Özgüdenli, Osman G. (15 November 2006). "Šāh-nāma Translations i. Into Turkish". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Blair, Sheila S. (1992). The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 11. ISBN 9004093672.

According to Ibn Bibi, in 618/1221 the Saljuq of Rum Ala' al-Din Kay-kubad decorated the walls of Konya and Sivas with verses from the Shah-nama

- Schimmel, Annemarie. "Turk and Hindu: A Poetical Image and Its Application to Historical Fact". In Islam and Cultural Change in the Middle Ages, ed. Speros Vryonis, Jr. Undena Publications, 1975. pp. 107–26. "In fact as much as early rulers felt themselves to be Turks, they connected their Turkish origin not with Turkish tribal history but rather with the Turan of Shahnameh: in the second generation their children bear the name of Firdosi’s heroes, and their Turkish lineage is invariably traced back to Afrasiyab—whether we read Barani in the fourteenth century or the Urdu master poet Ghalib in the nineteenth century. The poets, and through them probably most of the educated class, felt themselves to be the last outpost tied to the civilized world by the thread of Iranianism. The imagery of poetry remained exclusively Persian. "

- Ferdowsi (2006). Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Translated by Dick Davis. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670034851.

- Ferdowsi's poet, (2010). Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Translated by Reza Jamshidi Safa. Tehran, Iran.

- Christensen, Karen; Levinson, David, eds. (2002). Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 48. ISBN 0684806177.

- Azodi, Wiesehöfer (August 18, 2001). Ancient Persia: From 550 BC to 650 AD (New ed.). London: I. B. Tauris. p. Introduction. ISBN 1860646751.

- Nurian, Mahdi (1993). "Afarin Ferdowsi az Zaban Pishinian" [Praises of Ferdowsi from the Tongue of the Ancients]. Hasti Magazine. Tehran: Bahman Publishers. 4.

- Persian: "آفرين بر روان فردوسی / آن همايون نهاد و فرخنده / او نه استاد بود و ما شاگرد / او خداوند بود و ما بنده"

- Persian: "که فردوسی طوسی پاک مغز / بدادست داد سخنهای نغز / به شهنامه گیتی بیاراستست / بدان نامه نام نکو خواستست"

- Persian: "که از پیش گویندگان برد گوی"

- Persian: "زنده رستم به شعر فردوسی است / ور نه زو در جهان نشانه کجاست؟"

- Persian: "چه نکو گفت آن بزرگ استاد / که وی افکند نظم را بنیاد"

- Persian: "سخن گوی دانای پیشین طوسکه آراست روی سخن چون عروس"

- Persian: "شمع جمع هوشمندان است در دیجور غم / نکته ای کز خاطر فردوسی طوسی بود / زادگاه طبع پاکش جملگی حوراوش اند / زاده حوراوش بود چون مرد فردوسی بود"

- Persian: "باز کن چشم و ز شعر چون شکر / در بهشت عدن فردوسی نگر"

- Persian: "چه خوش گفت فردوسی پاکزاد / که رحمت بر آن تربت پاک باد / میازار موری که دانه کش است / که جان دارد و جان شیرین خوش است"

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- "Ten Most Expensive Books of 2006". Fine Books & Collections.

- ""Bayasanghori Shâhnâmeh" (Prince Bayasanghor's Book of the Kings)". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Lawrence, Lee (Dec 6, 2013). "Politics and the Persian Language". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2013.

- Simpson, Marianna Shreve (April 21, 2009). "ŠĀH-NĀMA iv. Illustrations". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Eduljee, K. E. "Ferdowsi Shahnameh Manuscripts". www.heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Michael Burgan (2009). Empire of the Mongols. Infobase Publishing. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-60413-163-5.

- Sarah Foot; Chase F. Robinson (25 October 2012). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 2: 400-1400. OUP Oxford. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-0-19-163693-6.

- Adamjee, Authors: Stefano Carboni, Qamar. "The Art of the Book in the Ilkhanid Period - Essay - Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History - The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- Komaroff, Authors: Suzan Yalman, Linda. "The Art of the Ilkhanid Period (1256–1353) - Essay - Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History - The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- Vladimir Lukonin; Anatoly Ivanov (30 June 2012). Persian Art. Parkstone International. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-1-78042-893-2.

- "Bahram Gur in a Peasant's House, Ilkhanid Dynasty". Khan Academy.

- "Leaf from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) « Islamic Arts and Architecture".

- "Style in Islamic Art (1250 - 1500 A.D) « Islamic Arts and Architecture".

- Blair, Sheila S. "Rewriting the History of the Great Mongol Shahnama". In Shahnama: The Visual Language of the Persian Book of Kings, ed. Robert Hillenbrand. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004. p. 35. ISBN 0754633675.

- Simpson, Marianna Shreve Simpson (7 May 2012). "Šāh-nāma iv. Illustrations". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Motlagh, Khaleghi; T. Lentz (15 December 1989). "Bāysonḡorī Šāh-nāma". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- John L. Esposito, ed. (1999). The Oxford History of Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 364. ISBN 0195107993.

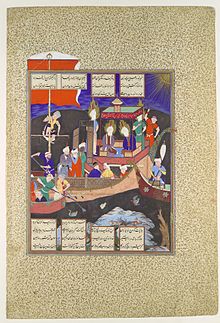

To support their legitimacy, the Safavid dynasty of Iran (1501–1732) devoted a cultural policy to establish their regime as the reconstruction of the historic Iranian monarchy. To the end, they commissioned elaborate copies of the Shahnameh, the Iranian national epic, such as this one made for Tahmasp in the 1520s.

- Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 445. ISBN 0521779332.

To bolster the prestige of the state, the Safavid dynasty sponsored an Iran-Islamic style of culture concentrating on court poetry, painting, and monumental architecture that symbolized not only the Islamic credentials of the state but also the glory of the ancient Persian traditions.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (2002). Discovering Islam: Making Sense of Muslim History and Society (2nd ed.). London: Psychology Press. p. 70. ISBN 0415285259.

Perhaps the high point was the series of 250 miniatures which illustrated the Shah Nama commissioned by Shah Ismail for his son Tahmasp.

- "Exhibition: Epic of the Persian Kings: The Art of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh". The Fitzwilliam Museum. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- "Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Persian Book of Kings". Freer and Sackler Galleries. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Fassihi, Farnaz (4: 58 pm ET May 23, 2013). "Shahnameh, a Persian Masterpiece, Still Relevant Today". The Wall Street Journal. IRAN.

- "Shahnameh : The Epic of the Persian Kings by Sheila Canby, Ahmad Sadri and Abolqasem Ferdowsi (2013, Hardcover) - eBay". www.ebay.com.

- Osmanov, M. N. O. "Ferdowsi, Abul Qasim". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Davis, Dick (Aug 1995). "Review: The Shahnameh by Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi, Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh". International Journal of Middle East Studies. Cambridge University Press. 27 (3): 393–395. JSTOR 176284.

- Loloi, Parvin (2014). "Šāh-Nāma Translations iii. Into English". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Lyden, Jacki. "'Heart' Of Iranian Identity Reimagined For A New Generation". NPR. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Producer's web site (Persian)

- "Iran animation invited to Cannes Film Festival - ISNA". En.isna.ir. 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- Farmanfarmaian, Fatema Soudavar (2009). Arjomand, Saïd Amir, ed. "Georgia and Iran: Three Millennia of Cultural Relations An Overview". Journal of Persianate Studies. BRILL. 2 (1). doi:10.1163/187471609X445464.

- Poet Moniruddin Yusuf (1919–1987) translated the full version of Shahnameh into the Bengali Language (1963–1981). It was published by the National Organisation of Bangladesh Bangla Academy, in six volumes, in February 1991.

- Borjian, Habib and Maryam Borjian. 2005–2006. The Story of Rostam and the White Demon in Māzandarāni. Nāme-ye Irān-e Bāstān 5/1-2 (ser. nos. 9 & 10), pp. 107–116.

- Shirzad Aghaee, Imazh-ha-ye mehr va mah dar Shahnama-ye Ferdousi (Sun and Moon in the Shahnama of Ferdousi, Spånga, Sweden, 1997. (ISBN 91-630-5369-1)

- Shirzad Aghaee, Nam-e kasan va ja'i-ha dar Shahnama-ye Ferdousi (Personalities and Places in the Shahnama of Ferdousi, Nyköping, Sweden, 1993. (ISBN 91-630-1959-0)

- Eleanor Sims. 1992. The Illustrated Manuscripts of Firdausī's "shāhnāma" Commissioned by Princes of the House of Tīmūr. Ars Orientalis 22. The Smithsonian Institution: 43–68. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4629424.

- A. E. Bertels (editor), Shax-nāme: Kriticheskij Tekst, nine volumes (Moscow: Izdatel'stvo Nauka, 1960–71) (scholarly Persian text)

- Jalal Khāleghi Motlagh (editor), The Shahnameh, in 12 volumes consisting of eight volumes of text and four volumes of explanatory notes. (Bibliotheca Persica, 1988–2009) (scholarly Persian text). See: Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University.

- Rostam: Tales from the Shahnameh, Hyperwerks, 2005, ISBN 0-9770213-1-9, about the story of Rostam & Sohrab.

- Rostam: Return of the King, Hyperwerks, 2007, ISBN 0-9770213-2-7, about the story of Kai-Kavous and Soodabeh.

- Rostam: Battle with The Deevs, Hyperwerks, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9770213-3-8, the story of the evil White Deev.

- Rostam: Search for the King, Hyperwerks, 2010, ISBN 978-0-9770213-4-5, the story of Rostam's childhood.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shahnameh. |

| Persian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Iraj Bashiri, Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, Iran Chamber Society, 2003.

- Encyclopædia Iranica entry on Baysonghori Shahnameh

- Pages from the Illustrated Manuscript of the Shahnama at the Brooklyn Museum

- Folios from the Great Mongol Shahnama at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Shahnameh Project, Cambridge University (includes large database of miniatures)

- Ancient Iran’s Geographical Position in Shah-Nameh

- A richly illuminated and almost complete copy of the Shahnamah in Cambridge Digital Library

- English translations by

- Helen Zimmern, 1883, Iran Chamber Society, MIT

- Arthur and Edmond Warner, 1905–1925, (in nine volumes) at the Internet Archive: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

- A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- Firdowsi & the Shahname | Kaveh Farrokh

- Text of the Shahnameh in Persian, section by section

沒有留言:

張貼留言