The emotionally intelligent person knows that love is a skill, not a feeling, and will require trust, vulnerability, generosity, humor, sexual understanding, and selective resignation.

The emotionally intelligent person awards themselves the time to determine what gives their working life meaning and has the confidence and tenacity to try to find an accommodation between their inner priorities and the demands of the world.

The emotionally intelligent person knows how to hope and be grateful, while remaining steadfast before the essentially tragic structure of existence.

The emotionally intelligent person knows that they will only ever be mentally healthy in a few areas and at certain moments, but is committed to fathoming their inadequacies and warning others of them in good time, with apology and charm.

There are few catastrophes, in our own lives or in those of nations, that do not ultimately have their origins in emotional ignorance. ~Alain de Botton

(Book: The School of Life https://amzn.to/4dPggOz)

(Art: Photograph of Paul Newman and wife Joanne Woodward)

| The School of Life 人才招募 | |

The School of Life 總部位於英國倫敦,由英國作家艾倫.狄波頓 (Alain de Botton) 於2009年創立,透過文化和人文學科,探討關於工作、愛情、 The School of Life 總部位於英國倫敦,由英國作家艾倫.狄波頓 (Alain de Botton) 於2009年創立,透過文化和人文學科,探討關於工作、愛情、目前台北辦公室正熱烈招募以下職缺。有興趣加入The School of Life Taipei 師資或團隊成員,請聯繫 taipei@theschooloflife.com 師資 Faculty www.theschooloflife.com/ 事業發展暨行銷經理 Business Development & Marketing Manager www.theschooloflife.com/ | |

Alain de Botton : The News: A User’s Manual ; 幸福建築...

陳玉慧觀點:我們需要好新聞

陳玉慧

2014年05月08日 10:47

全文網址: 陳玉慧觀點:我們需要好新聞 -風傳媒 http://www.stormmediagroup.com/opencms

Art Is Therapy review – de Botton as doorstepping self-help evangelist

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Alain de Botton has filled the Rijksmuseum with giant yellow Post-it notes that spell out his smarmy and banal ideas of self-improvement – but leaves us no room to look at the art

• Alain de Botton's exclusive video guide to Art is Therapy

Alain de Botton has filled the Rijksmuseum with giant yellow Post-it notes that spell out his smarmy and banal ideas of self-improvement – but leaves us no room to look at the art

• Alain de Botton's exclusive video guide to Art is Therapy

No eye, and no ear for language … the writer Alain de Botton at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Photograph: Vincent Mentzel

A flashing neon sign hangs over the grand entrance to the

Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Art Is Therapy, it reads, mirroring the cover

of Alain de Botton's recent book Art as Therapy, written with the philosopher and art historian John Armstrong.

The Rijksmuseum reopened last year

after major reorganisation and restoration, to almost universal

acclaim. It had more than 3 million visitors in 2013. They thought they

had a museum; what they have is a crammed-to-the-gills tourist

attraction. It's the Tate Modern effect.

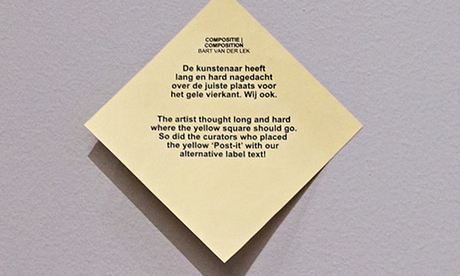

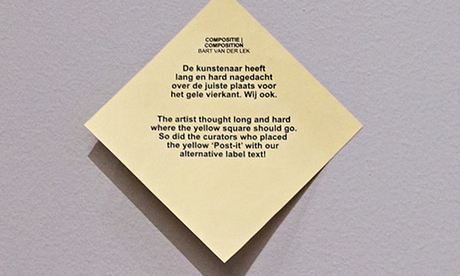

Perhaps troubled that 3 million visitors was not quite enough, Rijksmuseum director Wim Pijbes invited De Botton and Armstrong to make an "intervention". The authors have filled the place with loud, intrusive labels – giant Post-it notes that often dwarf the exhibits – along with a number of thematic displays.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels:

in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect

the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are

spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels:

in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect

the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are

spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

"You suffer from fragility, guilt, a split personality, self disgust," reads a note next to Jan Steen's 1660s genre painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas. "You are probably a bit like this picture," the label goes on. "There are sides of you that are a little debauched." The labels tell us what's wrong with us, and how the artworks and artefacts they accompany can cure our ills.

In front of Rembrandt's Night Watch, the crowning glory of the collection, another big yellow label tells us what it believes we are thinking: "I can't bear busy places – I wish this room were emptier." De Botton sees the Night Watch as an image of communality, which I suppose it is. There's not much fellow-feeling in the audience around it, and I guess that's the point, too.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair,

the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a

disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an

unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why

do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes,

under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the

saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the

people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this

old.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair,

the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a

disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an

unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why

do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes,

under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the

saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the

people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this

old.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade here. De Botton's curatorial rubrics – as well as memory, there's fortune, money, politics and sex – are anodyne, his insights and descriptions shallow and obvious. De Botton insists that art can tell us how to live: "It should heal us: it isn't an intellectual exercise, an abstract aesthetic arena or a distraction for a Sunday afternoon." His petulant tone is wearing. I also dislike the self-improvement shtick. In front of an athletic bit of statuary, a label inquires why, if we can accept going to the gym to improve our bodies, we don't visit the museum "to work on our character".

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians,

giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous

labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums

to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond

their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture.

He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education

departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in

self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians,

giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous

labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums

to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond

their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture.

He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education

departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in

self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

De Botton thinks we've got art all wrong. He doesn't like the way museums are organised and finds the usual little wall labels, with their dates and movements and snippets of art history, unhelpful. Ideally, he envisages museums reorganised according to therapeutic functions – with a basement of suffering, leading upwards to a gallery of self-knowledge on the top floor. It's like Dante's circles of hell.

De Botton's evangelising and his huckster's sincerity make him the least congenial gallery guide imaginable. He has no eye, and no ear for language. With their smarmy sermons and symptomology of human failings, their aphorisms about art leading us to better parts of ourselves, De Botton's texts feel like being doorstepped. But art contains concentrated doses of the virtues! You could coerce any art at all into his cause of mental hygiene and spiritual wellbeing. De Botton reduces art to its discernible content. He doesn't make us want to look at all.

Until 7 September. Details: +31 20 674 7000. Venue: Rijksmuseum.

- Alain de Botton and John Armstrong

- Art Is Therapy

- Rijksmuseum,

- Amsterdam

- Until 7 September

- Details:

+31 20 6747 000 - Venue website

Perhaps troubled that 3 million visitors was not quite enough, Rijksmuseum director Wim Pijbes invited De Botton and Armstrong to make an "intervention". The authors have filled the place with loud, intrusive labels – giant Post-it notes that often dwarf the exhibits – along with a number of thematic displays.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels:

in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect

the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are

spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels:

in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect

the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are

spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art."You suffer from fragility, guilt, a split personality, self disgust," reads a note next to Jan Steen's 1660s genre painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas. "You are probably a bit like this picture," the label goes on. "There are sides of you that are a little debauched." The labels tell us what's wrong with us, and how the artworks and artefacts they accompany can cure our ills.

In front of Rembrandt's Night Watch, the crowning glory of the collection, another big yellow label tells us what it believes we are thinking: "I can't bear busy places – I wish this room were emptier." De Botton sees the Night Watch as an image of communality, which I suppose it is. There's not much fellow-feeling in the audience around it, and I guess that's the point, too.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair,

the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a

disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an

unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why

do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes,

under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the

saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the

people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this

old.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair,

the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a

disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an

unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why

do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes,

under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the

saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the

people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this

old.Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade here. De Botton's curatorial rubrics – as well as memory, there's fortune, money, politics and sex – are anodyne, his insights and descriptions shallow and obvious. De Botton insists that art can tell us how to live: "It should heal us: it isn't an intellectual exercise, an abstract aesthetic arena or a distraction for a Sunday afternoon." His petulant tone is wearing. I also dislike the self-improvement shtick. In front of an athletic bit of statuary, a label inquires why, if we can accept going to the gym to improve our bodies, we don't visit the museum "to work on our character".

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians,

giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous

labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums

to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond

their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture.

He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education

departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in

self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp

De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians,

giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous

labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums

to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond

their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture.

He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education

departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in

self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.De Botton thinks we've got art all wrong. He doesn't like the way museums are organised and finds the usual little wall labels, with their dates and movements and snippets of art history, unhelpful. Ideally, he envisages museums reorganised according to therapeutic functions – with a basement of suffering, leading upwards to a gallery of self-knowledge on the top floor. It's like Dante's circles of hell.

De Botton's evangelising and his huckster's sincerity make him the least congenial gallery guide imaginable. He has no eye, and no ear for language. With their smarmy sermons and symptomology of human failings, their aphorisms about art leading us to better parts of ourselves, De Botton's texts feel like being doorstepped. But art contains concentrated doses of the virtues! You could coerce any art at all into his cause of mental hygiene and spiritual wellbeing. De Botton reduces art to its discernible content. He doesn't make us want to look at all.

Until 7 September. Details: +31 20 674 7000. Venue: Rijksmuseum.

沒有留言:

張貼留言