* 《馬爾泰手記》. 作者:里爾克; 方瑜譯:

- À Mon Seul Désir

The sixth tapestry is wider than the others, and has a somewhat different style. The lady stands in front of a tent, across the top of which is inscribed her motto "À Mon Seul Désir", one of the deliberately obscure, highly crafted and elegant mottos, often alluding to courtly love, adopted by the nobility during the age of chivalry. It is variously interpretable as "to my only/sole desire", "according to my desire alone"; "by my will alone", "love desires only beauty of soul", "to calm passion". Compare with the motto of Lady Margaret Beaufort (1441/3-1509) Me Sovent Sovant (Souvent me souviens, "Often I remember") which was adopted by St John's College, Cambridge, founded by her; also compare with the motto of John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford (1389-1435) A Vous Entier ("(Devoted) to you entirely"), etc. These frequently appear on artworks and illuminated miniatures. Her maidservant stands to the right, holding open a chest. The lady is placing the necklace she wears in the other tapestries into the chest. To her left is a low bench with a dog, possibly a Maltese sitting on a decorative pillow. It is the only tapestry in which she is seen to smile. The unicorn and the lion stand in their normal spots framing the lady while holding onto the pennants.

《馬爾特手記》曹元勇譯,上海文藝,2007,p.146

這本有些插圖,有點用心,可效果不見得好,譬如說,184頁,回憶"記憶中的死"的時候,說這是預知Rilke 晚年的"相":

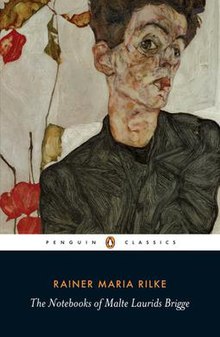

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

Rainer Maria Rilke

Robert Vilain

Oxford World's Classics

A new translation of Rilke's only novel, a canonical work of modernist prose that reflects the poet's own sense of alienation and transcends conventional narrative to achieve an intense exploration of imagination, perception, and language.

The story of Malte takes on representative status in an archetypal confrontation with the modern that is both intense and intriguingly unfocused.

The edition includes an authoritative introduction that helps to guide the reader through the narrative, draws biographical parallels and offers suggestions for interpretation. The text includes an alternative version of the ending rarely found in translations of the work.

Succinct and informative notes identify references and elucidate allusions, drawing parallels with other works by Rilke where appropriate, including his poetry.

"This edition, as so many Oxford World's Classics editions do, has just the perfect cover image... [an] excellent introduction by Robert Vilain." - Lisa Hill, ANZLitLovers

"For its notes this edition will be invaluable." - Charlie Louth, Times Literary Supplement

"A brilliant new translation." - JC, the Lady

"masterly translation" - Translation and Literature

"Reading Notebooks had a strange, dreamlike effect on me; the lines between past and present, real and unreal seemed blurred and it's a book that in many ways is hard to get a handle on.g the effort worthwhile, and I'm keen now to read some of Rilke's poetry." - Shiney New Books

""Notebooks" was an absorbing read, with the often beautiful and evocative prose making the effort worthwhile, and I'm keen now to read some of Rilke's poetry." - Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings

---

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Briggeby Rilke, Rainer Maria

https://archive.org/details/TheNotebooksOfMalteLauridsBrigge/page/n7/mode/2up

| |

| Author | Rainer Maria Rilke |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge |

| Translator | M. D. Herter Norton |

| Country | Austria-Hungary |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Autobiographical novel |

| Publisher | Insel Verlag |

Publication date | 1910 |

| Pages | Two volumes; 191 and 186 p. respectively (first edition hardcover) |

| Notre-Dame-des-Champs | |

|---|---|

Notre-Dame-des-Champs in 2012 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic Church |

| District | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Latin Rite |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 6th arrondissement, Paris, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°50′37″N 2°19′38″ECoordinates: 48°50′37″N 2°19′38″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Gustave Eiffel |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 1867 |

| Completed | 1876 |

| Website | |

| notredamedeschamps.fr | |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ M. D. Herter Norton (tr.). New York: W. W. Norton, 1949, 1992. Translator's Foreword, p. 8.

Full text of "The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge" - Internet Archive

https://archive.org/.../TheNotebooksOfMalteLauridsBrigge/TheNotebooksOfMalteLau...

THE NOTEBOOKS OF MALTE LAURIDS BRIGGE (Die Auf zeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge) by Rainer Maria Rilke Translated from the German by William ..

***The bare bones of Rainer Maria Rilke's life are as follows: He was born in 1875 in Prague to a snobbish mother disappointed with life and with her husband, a minor railway official. After going to military schools in Austria, he began writing, first in Prague, later on in Munich and Berlin, surviving as a reviewer and playwright, and virtually publishing himself. He had the most important relationship of his life with Lou Andreas-Salome, the wife of a Persian scholar and later a disciple of Freud's; she was successively lover, mother and confidante to him. When he broke with her, he quickly married the sculptor Clara Westhoff and lived with her in Worpswede, an artists' colony in northern Germany. Straight after the birth of a daughter, Ruth, in 1901, he took off for Paris, to write a monograph on Rodin (Clara's former teacher); subsequently, he became Rodin's secretary. Influenced by the atmosphere of incessant work around Rodin, he set himself daily exercise poems, which he published as the "New Poems" of 1907 and 1908. Many of his best-known pieces are there: "The Panther," "Self-Portrait From the Year 1906," "Archaic Torso of Apollo." He also began writing a novel, "The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge," a psychically and emotionally draining task, but an extraordinary and still insufficiently appreciated achievement.

---

"Life of a Poet," by Ralph Freedman, and "Uncollected Poems," a volume of English versions of Rilke by Edward Snow -- both part of an obviously undiminished fascination and pursuit -- represent two ways of coming at Rilke: the one through the life, the other by translating the poems. Both, obviously, end at one remove: the one with dates and places and people and events, the other with English. One amplifies what is unacceptable or -- not too strong a word -- repulsive about Rilke; the other struggles to convey what is great about him. Both seem to me likely to diminish Rilke -- though I'm sure that isn't the intent -- because a man's behavior and way of life don't require the filter of translation. Both books alter the balance in the same way, so that having read them, one is less prepared to say: yes, but it was worth it for the poetry. Rather, the poetry seems more and more like a disreputable and self-serving attempt to defend the indefensible.

***

.Books of the Times

By JOHN LEONARD

SLEEPLESS NIGHTS By Elizabeth Hardwick. |

![]() n her splendid interview with Richard Locke in last Sunday's New York Times Book Review, Elizabeth Hardwick mentioned her admiration for Rainer Maria Rilke's "The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge." She called it a "miraculous, perfect work."

n her splendid interview with Richard Locke in last Sunday's New York Times Book Review, Elizabeth Hardwick mentioned her admiration for Rainer Maria Rilke's "The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge." She called it a "miraculous, perfect work."

This catches a reviewer by not quite surprise. In the middle of "Sleepless Nights," I was thinking of Rilke's "Notebooks." I was also thinking of Renata Adler's "Speedboat" and Joan Didion's "Play It as It Lays." These are sad books, redeemed by language. The fragments, the shards, they pile up -- as though in the aftermath of a shattering explosion, an irreparable loss -- gleam, like diamonds or steel, and if you touch them they draw blood. So the center didn't hold. Perhaps there is no center. Perhaps the only center is the past. Perhaps the past doesn't hold either, and is merely the history of damages.

But let's stick for the moment with Rilke, because the Elizabeth of "Sleepless Nights" is a much more interesting mind than the Maria Wyeth of "Play It as It Lays," and we come to know her far better than we were allowed to know the Gen Fain of "Speedboat." Rilke sent Malte Brigge into the streets of turn-of-the-century Paris, where he found death. Miss Hardwick sends Elizabeth into another sort of city, a city of the self, where she finds death, too, and "the torment of personal relations." "Sweet," she says, "to be pierced by daggers at the end of paragraphs." It isn't sweet at all.

沒有留言:

張貼留言