A draft believed to be the origin story for Yasunari Kawabata’s “Fire” | KYODO

A draft believed to be the origin story for Yasunari Kawabata’s “Fire” | KYODOEarly this year, the team discovered a memo hinting at an alternative ending for “Snow Country.” Another discovery revealed a draft from the writer’s early 20s believed to be the origin story for the later published work “Fire.”

Elsewhere, publisher Shinchosha revealed that the recent standalone publication of Kawabata’s “The Boy” — a novel previously only available as part of his collected works — had been reprinted due to popular demand only seven days after its early April release.

Publication of the novel, a semi-autobiographical account of the protagonist’s erotic encounter with a classmate, received praise by contemporary playwright Hiroyuki Ono for its insight into the “soul of an orphan still walking with us today.”

Losing his entire family at an early age and eventually dying by his own hand, Kawabata’s solemn, sparse prose style, reminiscent of haiku poetry, painted beautiful and often haunting images of the time and place in which he lived.

The Nobel literature committee, on making Kawabata Japan’s first ever literary prize winner in 1968, cited the author’s “narrative mastery” and an ability to “express the essence of the Japanese mind.”

Contemporary Japanese literature scholar Sachiyo Taniguchi has written that the selectors “turned to Japanese literature as the result of deciding to correct the imbalance favoring Western writers” and that “Kawabata’s award came not only for his literature but was also an expression of international recognition of Japanese literature.”

Born in Osaka in 1899, Kawabata moved to Tokyo in 1917 to study, eventually graduating with a degree in Japanese literature from Tokyo University. He first gained national attention as a writer in 1926 with publication of the short story “The Dancing Girl of Izu.”

Often named as Kawabata’s most popular and well-known work in Japan, it was his first story translated into English. Subject of numerous on-screen adaptations, the story also inspired the Odoriko (dancing girl) nickname given to trains headed out from Tokyo toward Izu.

Kawabata’s literary fame grew throughout the late 1920s. In 1929, he began serialization of what would become “The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa,” a narrative drawing on his own experiences living among the working classes of downtown Tokyo’s notorious prewar entertainment district.

In 1934, he moved to Kamakura, home to a vibrant prewar literary scene. It was there that he began work on “Snow Country,” widely considered to be his masterpiece.

Deeply affected by the war, Kawabata’s postwar work became increasingly nostalgic for a Japan that was now fast receding into the past. In his late-career novel “Thousand Cranes” (1949), the male protagonist — newly intrigued by the tea ceremony — finds himself entangled in an increasingly complicated relationship with his deceased father’s former mistress and her daughter.

In 1961, he was awarded the Imperial Order of Culture, Japan’s highest cultural honor. He then won the race to become Japan’s first Nobel laureate in literature ahead of his good friend Yukio Mishima, who the committee deemed too young to win the prize.

The writer’s troubled final years were dogged by illness — he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease shortly before his death — and recurring nightmares featuring Mishima, who himself had taken his own life in 1970.

For Durham University scholar Fusako Innami, Kawabata’s influence remains evident in numerous artists in various mediums, both inside and outside Japan.

Overseas, Innami notes, it’s possible to draw parallels between the work of Kawabata and Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who refers specifically to Kawabata in his novel “Memories of My Melancholy Whores” (2004).

“Some of the themes and the way Kawabata conveys them speak to wider international audiences,” Innami said, explaining that his work can be read as sekai bungaku (world literature), despite it depicting Japanese icons such as hot springs and geisha.

It is this global appeal achieved through Japanese settings and themes that continues to generate considerable interest in Kawabata. The anniversary focus on his life and work is helping to provide new perspectives and insight into a figure who remains a genuine great of world literature.

Japan’s first Nobel literature laureate a towering figure 50 years after death

BY WILL FEE

The anniversary of the death of Yasunari Kawabata is being marked with an exhibition and a new adaptation of one of his works.

雪国

[BSプレミアム] [BS4K] 4月16日(土) 午後9:00 ~ 10:30

文豪・川端康成の没後50年。代表作を新たな視点で映像化。

文筆家・島村(高橋一生)は、訪れた雪国で芸者の駒子(奈緒)と出会う。一夜をともにする2人。だが、やがて島村は、駒子の心の中に、ある男女の影を見ることに…。

銀世界にたたずむ古い町並み、雪が降りしきる温泉宿など、美しい情景の中でつづられる繊細な心模様。原作の行間に隠された真実を、ミステリー要素も交えながらときほぐす。

【原作】川端康成

【出演】高橋一生,奈緒,森田望智,高良健吾,由紀さおり,山本郁子,あべかつのり,芹澤興人,川上友里,田根楽子,稲垣来泉,江藤雪乃,赤間麻里子,福澤重文,市島琳香,中上サツキ,松山傑

【脚本】藤本有紀

<インタビュー>

川端康成の代表作『雪国』をドラマ化!「美しい“言葉”と“余白”を感じてもえたら」(主演・高橋一生)

―from "Snow Country" by Yasunari Kawabata

- 雪国(1935年1月-1937年5月。1940年12月-1947年10月)

Nobel Laureate Yasunari Kawabata was born in Osaka, Japan on this day in 1899.

“The stars, almost too many of them to be true, came forward so brightly that it was as if they were falling with the swiftness of the void.”

―from SNOW COUNTRY

―from SNOW COUNTRY

Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country is widely considered to be the writer’s masterpiece: a powerful tale of wasted love set amid the desolate beauty of western Japan. At an isolated mountain hot spring, with snow blanketing every surface, Shimamura, a wealthy dilettante meets Komako, a lowly geisha. She gives herself to him fully and without remorse, despite knowing that their passion cannot last and that the affair can have only one outcome. In chronicling the course of this doomed romance, Kawabata has created a story for the ages — a stunning novel dense in implication and exalting in its sadness. READ an excerpt here: http://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/…/snow-country-by-yasuna…/

《美的交響世界:川端康成與東山魁夷》2006

川端康成と東山魁夷―響きあう美の世界 単行本 – 2006/9

文豪と画家、知られざる魂の邂逅。日本の美を追求した芸術家同士の素顔がのぞく往復書簡、発見される。直筆書簡、東山魁夷作品、国宝級の川端康成コレクション、一挙公開。

著者略歴 (「BOOK著者紹介情報」より)

川端/香男里

財団法人川端康成記念会理事長(本データはこの書籍が刊行された当時に掲載されていたものです)

財団法人川端康成記念会理事長(本データはこの書籍が刊行された当時に掲載されていたものです)

我是讀了川端康成的「末期の眼」之譯文 文中提到 古賀春江

去找一下

「お前はナニモノか」という問い ―古賀春江と川端康成と「末期の眼」(1)

古賀 春江(こが はるえ、1895年6月18日 - 1933年9月10日)は大正期に活躍した日本の初期のシュルレアリスムの代表的な洋画家(男性)である。本名は亀雄(よしお)。後に僧籍に入り「古賀良昌(りょうしょう)」と改名する。「春江」はあくまでも通称である。

他的生平有簡單的英文介紹

Harue Koga (古賀 春江 Koga Harue, June 18, 1895 - September 10, 1933) was a Japanese surrealist/avant-garde[1] painter active in the Taishō period.

His life

His real name is Yoshio. He entered the priesthood and was renamed "Ryosho Koga"; "Harue" is an alias. He was born as the eldest son of the priest of a buddhist temple, Zenfukuji. He belonged to the Pacific Ocean Painting Association Laboratory and the Japanese Watercolor Painting Laboratory after he had gone to Tokyo. He won Nika Prize for "Burial" in 1922. He established an art group "Action" in the same year. He devoted himself to Paul Klee between 1926 and 1927, and became good friends with Yasunari Kawabata.[1] A lot of his art works were influenced by the movements and painters in the West such as cubism (Fernand Léger), surrealism, Klee, etc., and his style changed one after another in a short term. In general, his work of several years following "Sea" is considered as the beginning of the surrealism painting in Japan, and had a big influence on the following Japanese arts. 九 抒情詩圏の画家――古賀春江

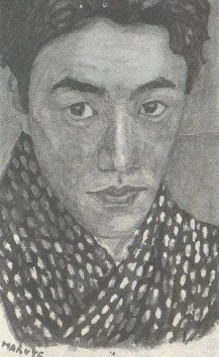

九 抒情詩圏の画家――古賀春江「絵はがき(自画像)」1916年

山の音 - Wikipedia

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/山の音

山の音』(やまのおと)は、川端康成の長編小説。戦後日本文学の最高峰と評され、第7

川端康成,譯者:葉渭渠

‘The Sound of the Mountain’: Yasunari Kawabata’s slow-burning meditation on getting older

BY LOUISE GEORGE KITTAKA

SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES

MAR 25, 2017

The first Japanese winner of the Nobel Prize in literature in 1968, Yasunari Kawabata, deals with the gradual decline that comes with aging in “The Sound of the Mountain.”

The Sound of the Mountain, by Yasunari Kawabata, Translated by Edward G. Seidensticker.

276 pages

TUTTLE, Fiction.

Family patriarch Shingo Ogata, a businessman nearing retirement, lives with his wife, son and daughter-in-law in Kamakura. Shingo has an affinity for the natural world, which serves as a metaphor for his feelings and reactions to events around him.

He is forced to ponder his own past performance as husband and father when both the marriages of his adult children run into trouble: Daughter Fusako leaves her husband, arriving home with her two small daughters, while her brother, Shuichi, neglects his own wife, Kikuyo, and brazenly carries on an affair. Shingo sees something of a kindred spirit in the devoted and gentle Kikuyo, and his affections for his daughter-in-law are a tad more than fatherly. At the same time, he feels guilt over a long-held infatuation for his late sister-in-law.

Despite his self-perceived shortcomings, Shingo is a sympathetic protagonist, and as he takes action to end his son’s affair and bring him back into the family fold, the book closes with a tentative sense of hope for a happier future for the Ogatas.

Kawabata delivers his characters and their dialogue in sensitively written prose that moves at a leisurely pace, and this domestic drama of is best enjoyed in the same manner.

First English-language edition

Author Yasunari Kawabata

Original title 山の音

Yama no Oto

Translator Edward Seidensticker

Country Japan

Language Japanese

Publication date 1949–1954

Published in English 1970 (Knopf)

Media type Print (paperback)

沒有留言:

張貼留言