Wikipedia

聖赫德嘉·馮·賓根(天主教譯聖賀德佳,聖公會譯聖希爾德格,德語:Hildegard von Bingen,拉丁文作Hildegardis Bingensis,1098年-1179年9月17日),又被稱為萊茵河的女先知(Sibyl of the Rhine),中世紀德國神學家、作曲家及作家。天主教聖人、教會聖師。她擔任女修道院院長、修院領袖,同時也是個哲學家、科學家、醫師、語言學家、社會活動家及博物學家。

簡歷[編輯]

在《拉丁教士集》第197卷(Patrologia Latina vol.197)中,修士郭德惠(Godefrid)與賽奧多歷(Theodoric)曾編寫過赫德嘉的生平簡歷。

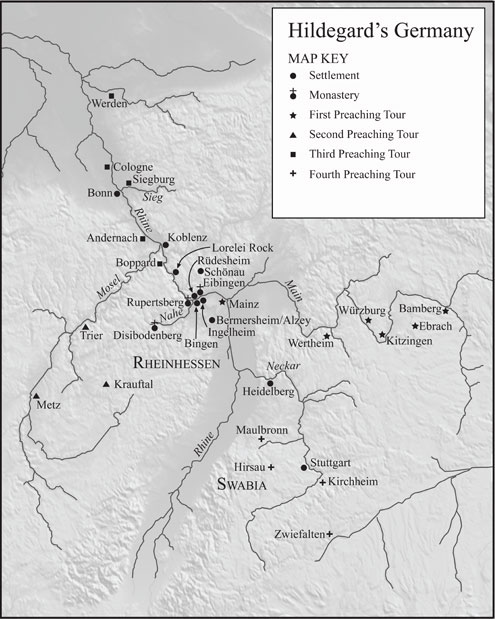

赫德嘉出身貴族家庭,屬斯龐海姆伯爵家族(Sponheim)領下,(斯龐海姆家族為霍亨斯陶芬王室"Hohenstaufen"的近親),她在家中排行第十,生來孱弱,所以在八歲時(這也有可能出於政治考量),父母便將她送給教會以抵替什一稅(tithe)。赫德嘉進入德國迪希邦登堡(Disibodenberg)附近一間修道院,歸由優塔監護(優塔原文Jutta,斯龐海姆家族的梅因哈德伯爵之姊妹)。當時優塔非常受人歡迎,吸引了許多追隨者,儼然形成一座小型女修院。1136年優塔死後,赫德嘉被選為這個社群的領導者,最後率眾移往萊因河邊賓根的魯伯斯堡(Rupertsberg),並成立一所新的修道院。她在文學與思想上的成就,也被後人拿來與但丁、威廉·布萊克相提並論。

12世紀是教派分立、宗教煽動行為盛行的時代,不管布講多麼古怪、多麼天差地遠的教義,都可能迅速集結一群信眾。赫德嘉對教派分立一事多所批判,事實上,她終生都在宣揚她反對教派分立的立場,特別是針對「卡特里派」(Cathar)。

她在很年輕時就曾表示自己有「靈視」(vision)。1141年,當她繼優塔被選為修院領導者五年後,赫德嘉受到了先知蒙召,命令她要「寫妳所見」。一開始,她對於是否要寫下自己靈視的內容仍躊躇不前、多所保留,但這讓她的心靈負著難言重擔,甚至造成了身體上的病痛,最後,她終於被修院成員說服,開始記下自己的靈視內容。

宗教覺醒[編輯]

在優塔身邊接受宗教教育的幾年間,赫德嘉只向優塔及另一位僧侶弗瑪(Volmar,後來成為赫爾嘉終生的書記)吐露過自己的靈視現象。1141年時,赫爾嘉的靈視扭轉了她的生命:在此次靈視中,上帝讓她頓悟各種經書文本的真義,並命令她寫下她在靈視中見到的一切。「接著……當我42歲又7個月的時候,天堂在我眼前開啟,有卓越智慧如眩目強光,流經我整個大腦,使我心胸彷彿起火,卻不感燒灼,而是溫暖……那些書本的意義乍然開朗……」(參見聖靈充滿)。

儘管如此,赫爾嘉仍感到自己完全不足,猶豫是否該採取行動:「雖然我看見了也聽見了,但因為不夠自信,又因為男人們所持的異見,很長一段時間我拒絕接受書寫的召喚──這並非出於固執,而是為了謙卑。直到上帝為此降罪於我,使我病臥不起。」

儘管從未懷疑過自己靈視的神聖來源,赫德嘉仍希望她的靈視能受到天主教會認可。她寫信給聖伯爾納鐸(St. Bernard of Clairvaux),期能獲得他的賜福。儘管給赫德嘉的回信寫得馬馬虎虎,他倒是確實把這件事情回報給教宗真福恩仁三世(Pope Eugene III,1145-1153),真福恩仁三世勉勵她寫完她的靈視內容,為了確定她是否確是受到神的啟發,他安排行程前往訪視赫德嘉,並宣布她並非精神錯亂,而是純正的密契者(mystic)。有了教皇的認可,赫德嘉終於敢完成她第一部記錄靈視內容的作品:《認識主道》(書名原文Scivias,英文意譯為"Know the Ways of the Lord"),並在1153年出版,名揚整個神聖羅馬帝國。

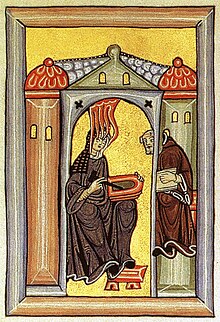

Illumination from the Liber Scivias showing Hildegard receiving a vision and dictating to her scribe and secretary

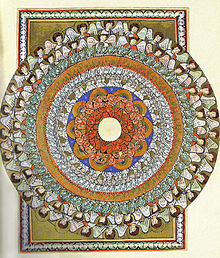

The Church, the Bride of Christ and Mother of the Faithful in Baptism. Illustration to Scivias II.3, fol. 51r from the 20th-century facsimile of the Rupertsberg manuscript, c. 1165–1180

赫德嘉逝世後被教廷封為聖人,2012年又被追贈教會聖師稱號,是天主教會史上第四位女性聖師。

赫德嘉的作品[編輯]

近代對中世紀教會史、女性史的學術研究,讓赫德嘉成為一個焦點人物,特別是她所創作的音樂。約有80首作品留存下來,數量遠超過絕大多數的中世紀作曲家,其中最為人熟知的是宗教劇(liturgical drama)〈美德典律〉(Ordo Virtutum),這是一齣早期的清唱劇,全由女聲組成,唯一的男聲即代表魔鬼。

赫德嘉許多樂曲作品都是為了宣揚福音所創作,表演者除了她領導的女修院成員之外,維勒的西多隱修會修道院(Cistercian Abbey at Villers)中的男性成員,也因見證了赫德嘉的才華而演出她的作品。她使用一種自行變體的中世紀拉丁文譜寫樂曲,時有造字、縮字與併字,所以,儘管音樂本身是單聲樂曲,後世仍需推敲這些曲目是否該在有限的情況下,配上樂器伴奏──例如搖弦琴(hurdy gurdy)或管風琴,這些曲目展現不同的人聲音域與調式,似也表明它們並不是只針對女聲所譜。除了音樂之外,赫德嘉也撰寫醫學、藥草學、地理學的論文,她還發明了一種「祕名語」(Lingua Ignota),以23個「祕名字母」(litterae ignotae)組成,大約有900個詞彙,可說是人造語言的前鋒。

1150年左右,赫德嘉帶領她日漸成長的修道院,從原駐的迪希邦登堡,搬到北方30公里處萊茵河畔的賓根地方,稍後又在賓根對岸的愛賓根建立了另一所修道院。儘管她的領導身分從未被該教區正式認可,但許多人在寫給赫德嘉的信件中,都稱她為院長。

赫德嘉晚年創作豐富,她寫歌、譜曲,多半是在宗教節日與慶典禮拜中,頌讚基督教聖人與聖母瑪麗亞的清唱曲以及讚美詩。文字作品方面,除了《認識主道》之外,另還有兩部記載靈視內容的主要作品,分別是1150年─1163年寫成的《生之功德書》(Liber vitae meritorum ),以及1163年寫成的《神之功業書》(Liber divinorum operum)。在上述兩部作品中,赫德嘉進一步詳細解釋了她的微觀神學與宏觀神學:人乃是上帝所造物中的頂峰,也是反射大千世界之美的一面鏡子。

赫德嘉尚著有《自然界》(Physica)與《病因與療法》(Causae et Curae),兩者對自然史及自然物的療效均有探討,遂被合稱為《自然奇妙百用之書》(Liber subtilatum),這幾本作品較不具赫德嘉的個人特色──也就是說,它們與靈視無關,也與神聖啟示無關,但內容中仍透露出赫德嘉的宗教哲學──人是萬物之靈,萬物為人效力。

赫德嘉的作品有一獨特之處——最早以女性觀點記述性的歡愉。「當女性與男性做愛,她的腦中便似起了火,這火帶來感官之樂,而在動作中享受感官之樂時,便會召喚男性的種子上前。一旦種子落入該落的地方,她腦中的烈火就逐漸熄滅,好能抓牢種子,很快地,女性的性器官便收縮,在月經時打開的外生殖器也關閉,就像一個強壯的男人把某樣物事緊緊把握在拳中。」她又寫道,孩子的性別取決於精子強度,而性情則取決於性交時愛與熱情的強度。據赫爾嘉所言,最糟的狀況,就是衰弱精子加上無感情的父母,那樣便會生出一個彆扭的女兒。

在赫德嘉書寫靈視的作品中,則一貫認為守貞即是最崇高的靈性生活,她的書信與靈視內容裡,一再出現不應耽慾的訊息。在《認識主道》中,她寫:

- 「上帝使男女相連,是要叫強的配上弱的,好能互補。但那些墮落的姦夫將他們的雄風,變成不正當的弱點,又抗拒合適的男女律則。他們因這般邪惡,成為撒但[註 1]可恥的追隨者,驕傲的撒但就想分化削弱祂。而他們因著邪惡,行下了怪異不宜的姦淫,我看去便覺得敗壞可恥。」

- 「……一名女子行魔鬼之道,與另一名女子配對,並扮演男子的角色,在我看來是最敗德之事。同樣地,將自己許給這樣女子的另一個女子,也是一樣。……」

- 「……碰觸自己的生殖器並射出精子的男人,靈魂便陷入嚴重危險,他們激起自己著魔似的性興奮,在我看來就像不純潔的獸類在毀壞自己的後代,因為他們產出精液的動機邪惡,只是一種敗壞褻瀆。……」

- 「當一個人感到自己受到生理刺激的困擾時,他應以克己節慾做為避難所,緊握純潔守貞之盾,抵抗不潔。」

注釋[編輯]

- ^ 查目前比較流行的聖經國語和合本、新標點和合本、和合本修訂版、現代中文譯本,還有比較古老的光緒19年福州美華書局活板文理聖經、光緒34年上海大美國聖經會官話串珠聖經、宣統3年聖經公會的文理聖經,Satan均譯作「撒但」,不作「撒旦」

*****A look at the fascinating life of Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), whose dazzling visions Oliver Sacks believed were caused by migraines. From BBC Music Magazine:

Artwork by Giada Rose Illustration

We take you through the extraordinary life of the 12-century nun: her many talents, achievements and visions.

15 November 2019 - 10:00am

You may think there were many people called Hildegard von Bingen: the one who catalogued the animals, birds, fish, plants, trees and precious metals of her native German Rhineland; the one whose medical theories are still valued by holistic therapists today; the one who invented her own, mysterious language of 900 words, its intention a continuing debate among scholars.

Perhaps more famous is the writer, theologian and abbess, whose bold, arresting visions – many depicted in illuminated manuscripts – reflected her own fervent beliefs; who founded her own monastery; who stood up to monks, bishops, popes and emperors across Europe, the scourge of a corrupt Church, earning her the name ‘Sibyl of the Rhine’.

Finally, there is Hildegard the musician: one of the first named composers and the woman who concerns us here. We cannot separate these strands of Hildegard’s long and eventful life any more than she could herself.

In certain respects, her biography is well documented. The facts we know give us vital context to grasp how a barely educated woman could move so relatively freely in the highest echelons of medieval life. However, frustratingly little is known about her musical interests or practice.

Hildegard was born in Alzey in the wine-growing region of Rheinhessen in 1098, though with an almost mystical respect for the harmony of round numbers, she herself recorded the date as 1100.

Her parents were land owners, middle-ranking, but not grand. Likely to have been the tenth child, she was given as a tithe to the church, either at eight or 14. Immediately, her childhood acquires fascination. The habit of donating a child, a voluntary form of tax, was relatively common, but Hildegard had already proved herself an exception.

At a young age, and throughout her life, she had visions, believed to be sent from God. These set her apart, in every sense. (In our own time, the British neurologist Oliver Sacks suggested these visions, which were accompanied by severe, debilitating physical symptoms, were akin to migraines.)

Wrenched from her family, she was enclosed as an anchoress with another well-born, older girl, Countess Jutta von Sponheim – they lived in a cell alongside, but segregated from, monks in the hillside abbey of Disibodenberg. The idea of anchorage was to be ‘buried’ from the world and rise again in immortality through sequestration and prayer. This would be Hildegard’s home, and mode of existence, for more than three decades.

Remote though this existence sounds, political and religious life in 12th-century Europe had a direct impact on Hildegard’s life. It was the time of Crusades, pilgrimage, cathedral building; the era of the grand monasteries of Cluny, religious fervour – and attendant profiteering and abuse of power by clergy. Monastic life, in its timetable of work and prayer, was yoked to the Rule of St Benedict.

Yet monasteries were also places of learning, and of refuge for travellers and the sick: monks and nuns were secluded from the world, but the world came to them. Women, for a brief period in history, could hold a fair degree of power. (This would diminish by the end of Hildegard’s life, when universities, closed to women, began to flourish.)

Hildegard’s full story, rich in episode and colour, can only be told here in highlights. A turning point was the death of Jutta, who had given her a rudimentary education, perhaps in music as well as Latin. A number of other young women (and their all-too useful dowries) having arrived at the anchorage in the intervening years, Hildegard now succeeded Jutta as abbess.

By now she was in her 40s, with a growing sense of purpose. She began to write her best-known theological work, Scivias(or Know the Way), assisted by her secretary and friend, the monk Volmar. Moreover she also, according to the Vita Sanctae Hildegardis (Life of St Hildegard) written by two monks during and after her lifetime, began composing music for the first time – for her nuns to sing as part of the Divine Office.

Causing some shock among her colleagues, Hildegard left Disibodenberg and founded her own monastery at Rupertsberg, on the banks of the Rhine, where it meets the river Nahe, at Bingen. Now, as then, one of the Rhine’s busiest junctions, it was a canny choice. She wanted more room and prominence. The wealthy families who gave their daughters to the church wanted greater comfort and physical protection.

It was the start of a radically different stage of life, in which she travelled throughout Europe, met leading figures of the day, debated, sermonised, wrote hundreds of letters (which have survived, and now exist in a modern edition).

Hildegard von Bingen, because of her celebrity and achievements, her writings and visions and, above all, her music, is remembered. She died in 1179 aged 81, after battles with her health and with the Church, weary of ‘this present life’. When she passed away, two arcs of colour reportedly illuminated the sky as ‘the holy virgin gave her happy soul to God’, a fitting miracle for one who, more than 800 years later, in 2012, would be made a saint.

Her spirit lives on, as fierce, defiant, creative and brilliant as ever.

沒有留言:

張貼留言