Everyman's Library

"Wherever your life ends, it is all there. The advantage of living is not measured by length, but by use; some men have lived long, and lived little; attend to it while you are in it. It lies in your will, not in the number of years, for you to have lived enough."

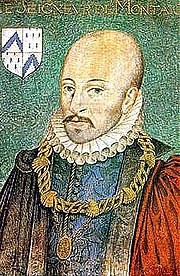

--from "The Complete Works" by Michel de Montaigne, who died on this day in 1592

Humanist, skeptic, acute observer of himself and others, Michel de Montaigne (1533—92) was the first to use the term “essay” to refer to the form he pioneered, and he has remained one of its most famous practitioners. He reflected on the great themes of existence in his wise and engaging writings, his subjects ranging from proper conversation and good reading, to the raising of children and the endurance of pain, from solitude, destiny, time, and custom, to truth, consciousness, and death. Having stood the test of time, his essays continue to influence writers nearly five hundred years later. Also included in this complete edition of his works are Montaigne’s letters and his travel journal, fascinating records of the experiences and contemplations that would shape and infuse his essays. Montaigne speaks to us always in a personal voice in which his virtues of tolerance, moderation, and understanding are dazzlingly manifest. Donald M. Frame’s masterful translation is widely acknowledged to be the classic English version.

In Praise of Travel, Particularly on Horseback

By Antoine Compagnon May 24, 2019

ARTS & CULTURE

CAROLUS-DURAN, EQUESTRIAN PORTRAIT OF MADEMOISELLE CROIZETTE, 1873, OIL ON CANVAS. PUBLIC DOMAIN, VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

Michel de Montaigne is best imagined on horseback; firstly, because that was how he traveled around his own lands and between his estate and Bordeaux, as well as elsewhere in France—to Paris, Rouen, or Blois, and even farther afield (during his great journey in 1580 he traveled through Switzerland and Germany all the way to Rome). But he should also be pictured this way because he never felt more comfortable anywhere than in the saddle; it was here that he found his equilibrium, his seat:

Travel is in my opinion a very profitable exercise; the soul is there continually employed in observing new and unknown things, and I do not know, as I have often said a better school wherein to model life than by incessantly exposing to it the diversity of so many other lives, fancies, and usances, and by making it relish a perpetual variety of forms of human nature. The body is, therein, neither idle nor overwrought; and that moderate agitation puts it in breath. I can keep on horseback, tormented with the stone as I am, without alighting or being weary, eight or ten hours together.

First of all, traveling enables us to experience the world’s diversity, and Montaigne insists that there is no better education. Traveling shows us the richness of nature, proves the relativity of customs and beliefs, and shakes up our certainties; in short, it teaches us skepticism, which was Montaigne’s fundamental doctrine.

Next, Montaigne gains particular physical pleasure from riding horseback, which allies movement and stability and gives the body balance and rhythm conducive to contemplation. Riding frees us from work without encouraging idleness; it lends itself to daydreaming. Horseback riding puts Montaigne in a state of “moderate agitation,” a lovely combination of terms he uses to designate a sort of ideal intermediary state. Aristotle both thought and taught while walking; Montaigne has his best ideas while in the saddle, an activity that even allows him to forget about his bladder and kidney stones.

However, Montaigne also admits—as is his wont—that his taste for travel, particularly on horseback, could also be interpreted as a mark of indecision and powerlessness: “I know very well that, to take it by the letter, this pleasure of travelling is a testimony of uneasiness and irresolution, and, in sooth, these two are our governing and predominating qualities. Yes, I confess, I see nothing, not so much as in a dream, in a wish, whereon I could set up my rest: variety only, and the possession of diversity, can satisfy me; that is, if anything can. In travelling, it pleases me that I may stay where I like, without inconvenience, and that I have a place wherein commodiously to divert myself.”

To be too fond of traveling is to prove yourself incapable of stopping, of making a decision, of settling down; it is to lack confidence, to prefer inconsistency to perseverance. In this, for Montaigne, travel is a metaphor for life. He lives like he travels—aimlessly, open to the attractions of the world: “They who run after a benefit or a hare, run not … and the journey of my life is carried on after the same manner.”

So great is Montaigne’s love of riding that if he were able to choose the manner of his death, “I think I should rather choose to die on horseback than in bed.” Montaigne dreamed of dying in the saddle, off on some voyage, far from his home and family. Life and death on horseback represent his philosophy perfectly.

—Translated from the French by Tina Kover

Antoine Compagnon is a professor of French literature at Collège de France, Paris, and the Blanche W. Knopf Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, New York. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary degrees from King’s College London, HEC Paris, and the University of Liege.

Tina Kover’s translations include Négar Djavadi’s novel, Disoriental, which was short-listed for the National Book Award; Anna Gavalda’s Life, Only Better; and The Little Girl on the Ice Floe, by Adélaïde Bon. Kover is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship for the translation of Manette Salomon, by the Goncourt brothers.

Excerpted from A Summer with Montaigne, by Antoine Compagnon, translated by Tina Kover. A Summer with Montaigne is published by Europa Editions.

Yale University Press 新增了 1 張相片。

Michel de Montaigne gives advice to UK education secretary, 教育的浪費

蒙田《随筆集》內。有許多教育學等方面的宏文.....光是篇名上有"教育"字眼的,就有3篇:

論教育

論兒童教育

我譴責教育上的一切體罰

梁宗岱 黃建華《蒙田隨筆》1987 =《我不想樹立雕像》北京: 光明日報出版社1996

本書作者蒙田以懷疑論抨擊教會與封建制度、批判經院哲學,是“崇尚自然、崇尚自我”這一口號主要力行者之一.

目錄 · · · · · ·

第一部分

論不同的方法可以收同樣的效果

論悲哀

論靈魂缺乏真正物件時把情感寄託在假定物件上

論閒逸

論說誑

論辯才的急慢

論預兆

論善惡之辨大抵系於我們的意識

論恐怖

論死後才能斷定我們的幸福

論哲學即是學死

論想像的力量

我們的感情延續到死後

論隱逸

論教育

論憑我們的見識來評定真假之狂妄

我們怎樣為同一事物哭笑

論友誼

論人與人之間的不平等

論兒童教育

――致馬丹迪安納 特・華特 格爾遜夫人的信

第二部分

自畫像

自畫像之二

我不想樹立雕像

易變無常

熱愛生命

要生活得寫意

多少回我成非我

病重

死之經驗

友誼的奧秘

我的書房

我當市長

介人抑或棄權

描繪人

人體之重要

人之常規

醜惡的靈魂

守舊表現其外,自由思想其中

自命不凡的虛妄

眾師之師 ――人類的無知

盡情享受生活之樂趣

我譴責教育上的一切體罰

人 ――可憐的“怪物”

法律

新舊世界

有血有肉的語言

詩之自由隨意

致讀者

論不同的方法可以收同樣的效果

論悲哀

論靈魂缺乏真正物件時把情感寄託在假定物件上

論閒逸

論說誑

論辯才的急慢

論預兆

論善惡之辨大抵系於我們的意識

論恐怖

論死後才能斷定我們的幸福

論哲學即是學死

論想像的力量

我們的感情延續到死後

論隱逸

論教育

論憑我們的見識來評定真假之狂妄

我們怎樣為同一事物哭笑

論友誼

論人與人之間的不平等

論兒童教育

――致馬丹迪安納 特・華特 格爾遜夫人的信

第二部分

自畫像

自畫像之二

我不想樹立雕像

易變無常

熱愛生命

要生活得寫意

多少回我成非我

病重

死之經驗

友誼的奧秘

我的書房

我當市長

介人抑或棄權

描繪人

人體之重要

人之常規

醜惡的靈魂

守舊表現其外,自由思想其中

自命不凡的虛妄

眾師之師 ――人類的無知

盡情享受生活之樂趣

我譴責教育上的一切體罰

人 ――可憐的“怪物”

法律

新舊世界

有血有肉的語言

詩之自由隨意

致讀者

*****

《蒙田隨筆全集》(全三冊)

作者: [法國] 蒙田

譯者: 潘麗珍 等

出版社: 譯林出版社1996 台灣商務2006

《蒙田隨筆全集》共107章,百萬字左右。其中最著名的一篇為《為雷蒙·塞蓬德辯護》,充分表達了他的懷疑論的哲學思想。

蒙田以博學著稱,在全集中,日常生活、傳統習俗、人生哲理等等無所不談,特別是旁證博引了許多古希臘羅馬作家的論述。書中,作者還對自己作了大量的描寫 與剖析,使人讀來有娓娓而談的親切之感,增加了作品的文學趣味。它是十六世紀各種思潮和各種知識經過分析的總匯,有“生活的哲學”之美稱。書中語言平易通 暢,不假雕飾,在法國散文史上佔有重要地位,開創了隨筆式作品之先河。

這部作品卷帙浩繁,用古法文寫成,又引用了希臘、義大利等國的語言,以 及大量拉丁語,因此翻譯難度相當大。本社積累了組譯出版《追憶似水年華》的成功經驗,採用了蒙田死後於1595年經過增訂的定本,於1993年開始組譯, 歷經四年之久,分成三卷一次推出。這是蒙田隨筆的第一個全譯本,參與該書的譯者都是研究和翻譯法國文學富有經驗的學者,為譯出蒙田隨筆特有的思想火花和語 言魅力,各位譯者都付出了巨大的努力,翻譯態度是極為嚴謹的,讀者可以從中真實地窺見到蒙田的思想、風格及他所生活的時代的風俗民情蒙田在文中論述的有些 觀點也許未必正確,但讀者可以從隨筆的總體上吸收他的思想和藝術精華,並收到啟智怡情的功效。

蒙田以博學著稱,在全集中,日常生活、傳統習俗、人生哲理等等無所不談,特別是旁證博引了許多古希臘羅馬作家的論述。書中,作者還對自己作了大量的描寫 與剖析,使人讀來有娓娓而談的親切之感,增加了作品的文學趣味。它是十六世紀各種思潮和各種知識經過分析的總匯,有“生活的哲學”之美稱。書中語言平易通 暢,不假雕飾,在法國散文史上佔有重要地位,開創了隨筆式作品之先河。

這部作品卷帙浩繁,用古法文寫成,又引用了希臘、義大利等國的語言,以 及大量拉丁語,因此翻譯難度相當大。本社積累了組譯出版《追憶似水年華》的成功經驗,採用了蒙田死後於1595年經過增訂的定本,於1993年開始組譯, 歷經四年之久,分成三卷一次推出。這是蒙田隨筆的第一個全譯本,參與該書的譯者都是研究和翻譯法國文學富有經驗的學者,為譯出蒙田隨筆特有的思想火花和語 言魅力,各位譯者都付出了巨大的努力,翻譯態度是極為嚴謹的,讀者可以從中真實地窺見到蒙田的思想、風格及他所生活的時代的風俗民情蒙田在文中論述的有些 觀點也許未必正確,但讀者可以從隨筆的總體上吸收他的思想和藝術精華,並收到啟智怡情的功效。

蒙田的作品都是長期困頓、思索的結晶,因此也反應寫作當時所關心的問題。

蒙田是一個活在古代的現代人。他不朽的隨筆,充滿著冷峻的觀察、辛辣而幽默的批判、豐富的知識、出入今古的精採摘錄。

他無所不談,自有見地,留下的精神財富使後人至今不感匱乏。

然而他說:我知道什麼?

他無所不談,自有見地,留下的精神財富使後人至今不感匱乏。

然而他說:我知道什麼?

在他《隨筆集》中卷裡,他仍以自由的筆調、旁徵博引和懷疑論的風格,暢敘矛盾、野心、勇氣、良心、痛苦和死亡。

他從懷疑論導向對自我的挖掘、探索,並從自身擴而及於所有的人,以之作為人性的學校,以為人可以因此獲致精神上的獨立,確認本來面目,得到真正的智慧與幸福。

中卷也包含了他《隨筆集》裡篇幅最長的一章〈雷蒙.塞邦贊〉,為無名的西班牙作家雷蒙.塞邦辯護,抨擊了禁慾主義和教條主義。

他從懷疑論導向對自我的挖掘、探索,並從自身擴而及於所有的人,以之作為人性的學校,以為人可以因此獲致精神上的獨立,確認本來面目,得到真正的智慧與幸福。

中卷也包含了他《隨筆集》裡篇幅最長的一章〈雷蒙.塞邦贊〉,為無名的西班牙作家雷蒙.塞邦辯護,抨擊了禁慾主義和教條主義。

關於蒙田,人們以為可說的都已說盡:他是懷疑論者,他向自己發問而又不作回答,甚至拒絕承認自己一無所知,而只是堅持那句「我知道什麼」的名言。於是,對一個真理的否定,揭示出一個新的真理。

*****

書 名:《蒙田隨筆全集》

作 者: [法] 蜜雪兒·德·蒙田

譯 者: 馬振騁

出 版: 上海書店出版社,2009年

“我知道什麼?”——蒙田和《蒙田隨筆》馬振騁一蜜雪兒·德·蒙田(1533-1592),生於法國南部佩里戈爾地區的蒙田城堡。父親是繼承了豐厚家產的商人,有貴族頭銜,他從義大利帶回一名不會說法語的德國教師,讓蜜雪兒三歲尚未學法語以前先向他學拉丁語作為啟蒙教育。不久,父親被任命為波爾多市副市長,全家遷往該市。1548年,蒙田到圖盧茲進大學學習法律,年二十一歲,在佩里格一家法院任推事。1557年後在波爾多各級法院工作。1562年在巴黎最高法院宣誓效忠天主教,其後還曾兩度擔任波爾多市市長。1568年,父親過世,經過遺產分割,蒙田成了蒙田莊園的領主。三年後,才三十八歲的蒙田就開始過起了退隱讀書生活,回到蒙田城堡,“投入智慧女神的懷抱,在平安寧靜中度過有生之年”。那時候,宗教改革運動正在歐洲許多國家如火如荼地進行,法國胡格諾派與天主教派內戰更是從1562年打到了1598年,亨利四世改宗天主教,頒佈南特敕令,寬容胡格諾派,戰事才告平息。蒙田只是回避了繁雜的家常事務,實際上風聲雨聲讀書聲,聲聲都聽在耳裏。他博覽群書,反省、自思、內觀,那時舊教徒以上帝的名義、以不同宗派為由任意殺戮對方,誰都高唱自己的信仰是唯一的真理,蒙田對這一切冷眼旁觀,卻提出令人深思的雋言:“我知道什麼?”他認為一切主義與主張都是建立在個人偏見與信仰上的,這些知識都只是片面的,只有返回到自然中才能恢復事物的真理,有時不是人的理智能夠達到的。“我們不能肯定知道了什麼,我們只能知道我們什麼都不知道,其中包括我們什麼都不知道。”二從1572年起,蒙田在閱讀與生活中隨時寫下許多心得體會,他把自己的文章稱為Essai。這詞在蒙田使用以前只是“試驗”、“試圖”等意思,例如試驗性能、試嘗食品。他使用Essai只是一種謙稱,不妄圖以自己的看法與觀點作為定論,只是試論。他可以夾敘夾議,信馬由韁,後來倒成了一種文體,對培根、蘭姆、盧梭(雖然表面不承認)都產生了很大影響。在我國則把Essai一詞譯為“隨筆”。這是一部從1572至1592年逝世為止,真正歷時二十年寫成的大部頭著作,也是蒙田除了他逝世一百八十二年後出版的《義大利遊記》以外的唯一作品。從《隨筆》各篇文章的寫作時序來看,蒙田最初立志要寫,但是要寫什麼和如何寫,並不成竹在胸。最初的篇章約寫於1572至1574年,篇幅簡短,編錄一些古代軼事,摻入幾句個人感想與評論。對某些縈繞心頭的主題,如死亡、痛苦、孤獨與人性無常等題材,摻入較多的個人意見。隨著寫作深入,章節內容也更多,結構也更鬆散,在表述上也更具有個人色彩和執著,以致在第二卷中間寫出了最長也最著名的《雷蒙·塞邦贊》,把他的懷疑主義闡述得淋漓盡致。這篇文章約寫於1576年,此後蒙田《隨筆》的中心議題明顯偏重自我描述。1580年,《隨筆》第一、二卷在波爾多出版。蒙田在6月外出旅遊和療養,經過巴黎,把這部書呈獻給亨利三世國王。他對國王的讚揚致謝說:“陛下,既然我的書王上讀了高興,這也是臣子的本分,這裏面說的無非是我的生平與行為而已。”蒙田在義大利暢遊一年半後,回到蒙田城堡塔樓改建成的書房裏,還是一邊繼續往下寫他的《隨筆》,一邊不斷修改;一邊出版,一邊重訂,從容不迫,生前好像沒有意思真正要把它做成一部完成的作品。他說到理智的局限性、宗教中的神性與人性、藝術對精神的療治作用、兒童教育、迷信占卜活動、書籍閱讀、戰馬與盔甲的利用、異邦風俗的差異……總之,生活遇到引起他思維活動的大事與小事,從簡單的個人起居到事關黎民的治國大略,蒙田無不把他們形之於筆墨。友誼、社交、孤獨、自由,尤其是死亡等主題,還在幾個章節內反復提及,有時談得還不完全一樣,有點矛盾也不在乎,因為正如他說的,人的行為時常變化無常。他強調的“真”還是劃一不變。既然人在不同階段會有不同的想法與反應,表現在同一個人身上,這些不同人依然是正常的“真”性情。蒙田以個人為起點,寫到時代,寫到人的本性與共性。他深信談論自己,包含外界的認識、文化的吸收和自我的享受,可以建立普遍的精神法則,因為他認為每個人自身含有人類處境的全部形態。他用一種內省法來描述自己、評價自己,也以自己的經驗來對證古代哲人的思想與言論;可是他也承認這樣做的難度極高,因為判定者與被判定者處於不斷變動與搖擺中。這種分析使他看出想像力的弊端與理性的虛妄,都會妨礙人去找到真理與公正。蒙田的倫理思想不是來自宗教信仰,而是來自古希臘這種溫和的懷疑主義。他把自己作為例子,而不是作為導師。他認為認識自己、控制自己、保持內心自由,通過獨立判斷與情欲節制,明智地實現自己的本質,那時才會使自己成為“偉大光榮的傑作”。文藝復興以前,在經院哲學一統天下的歐洲,人在神的面前一味自責、自貶、自抑。文藝復興時期,人文主義思想抬頭,人發現了自己的價值、尊嚴與個性,把人看作是天地之精華,萬物之靈秀。蒙田身處長年戰亂的時代,同樣從人文主義出發,更多指出人與生俱來的弱點與缺陷,要人看清自己是什麼,然後才能正確對待自己、他人與自然,才能活得自在與愜意。三法國古典散文有三大家:拉伯雷、加爾文與蒙田。拉伯雷是法國文藝復興時期智慧的代表人物,博學傲世,對不合理的社會冷嘲熱諷,以《巨人傳》而成不朽。加爾文是法國宗教改革先驅。當時教會指導世俗,教會不健全則一切不健全,他認為要改革必先改革宗教。他的《基督教制度》先以拉丁語出版,後譯成法語,既是宗教也是文學方面名著。蒙田的《隨筆》則是法國第一部用法語書寫的哲理散文。行文旁徵博引,非常自在,損害詞義時決不追求詞藻華麗,認為平鋪直敍勝過轉彎抹角。對日常生活、傳統習俗、人生哲學、歷史教訓等無所不談,偶爾還會文不對題。他不說自己多麼懂,而強調自己多麼不懂,在這“不懂”裏面包含了許多真知灼見。不少觀點令人嘆服其前瞻性,其中關於“教育”、“榮譽”、“對待自然與生活的態度”、“姓名”、“預言”的觀點更可令人聽了汗顏。城堡領主,兩任波爾多市市長,說拉丁語的古典哲理散文家,聽到這麼一個人,千萬別以為他是個道貌岸然的老夫子。蒙田在生活與文章中幽默俏皮。他說人生來有一個腦袋、一顆心和一個生殖器官,各司其職。人歷來對腦袋與心談得很多,對器官總是欲說還休。蒙田所處的時代,相當於中國明朝萬曆年間,對婦女的限制也並不比明朝稍松,他在《隨筆》裏不忌諱談兩性問題,而且談得很透徹,完全是個性情中人。當然這位老先生不會以開放的名義教人紅杏出牆或者偷香竊玉。他只是說性趣實在是上帝惡作劇的禮物,人人都有份,也都愛好。在這方面,沒有精神美毫不減少聲色,沒有肉體美則味同嚼蠟。只是人生來又有一種潛在的病,那就是嫉妒。情欲有時像野獸不受控制,遇到這類事又產生尷尬的後果,不必過於死心眼兒,他說歷史上的大人物,如“盧庫盧斯、愷撒、龐培、安東尼、加圖,和其他一些英雄好漢都戴過綠帽子,聽到這件事並不非得拼個你死我活”。這帖蒙氏古方心靈雞湯,喝下去雖不能保證除根有效,也至少讓人發笑,有益健康,化解心結。蒙田說:“我不是哲學家。”他的這句話與他的另一句話:“我知道什麼?”當然都不能讓人從字面價值來理解。記得法國詩人瓦萊裏說過這句俏皮話:“一切哲學都可以歸納為辛辛苦苦在尋找大家自然會知道的東西。”用另一句話來說,確實有些哲學家總是把很自然可以理解的事說得複雜難懂。蒙田的後大半生是在胡格諾戰爭時期度過的。他在混沌亂世中指出人是這樣的人,人生是這樣的人生。人有七情六欲,必然有生老病死。人世中有險峻絕壁,也有綠野仙境。更明白昨天是今日的過去,明天是此時的延續。“光明正大地享受自己的存在,這是神聖一般的絕對完美。”“最美麗的人生是以平凡的人性作為楷模,有條有理,不求奇跡,不思荒誕。”蒙田文章語調平易近人,講理深入淺出,使用的語言在當時也通俗易懂。有人很恰當地稱為“大眾哲學”。他不教訓人,他只說人是怎麼樣的,找出快樂的方法過日子,這讓更多的普通人直接獲得更為實用的教益。早在十九世紀初,已經有人說蒙田是當代哲學家。直至最近進入了二十一世紀,法國知識份子談起蒙田,還親切地稱他是我們這個時代的賢人,仿佛在校園裏隨時可以遇見他似的。

英文書信與散文全集

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3600/3600-h/3600-h.htm

Translated by Charles Cotton 1877

PREFACE

THE LETTERS OF MONTAIGNE

I.To Monsieur de MONTAIGNE

II.To Monseigneur, Monseigneur de MONTAIGNE.

III.To Monsieur, Monsieur de LANSAC,

IV.To Monsieur, Monsieur de MESMES, Lord of Roissy and Malassize, Privy

V.To Monsieur, Monsieur de L'HOSPITAL, Chancellor of France

VI.To Monsieur, Monsieur de Folx, Privy Councillor, to the Signory of Venice.

VII.To Mademoiselle de MONTAIGNE, my Wife.

VIII. To Monsieur DUPUY,

IX.To the Jurats of Bordeaux.

X.To the same.

XI.To the same.

XII.

XIII.To Mademoiselle PAULMIER.

XIV.To the KING, HENRY IV.

XV.To the same.

XVI.To the Governor of Guienne.

BOOK THE FIRST CHAPTER ITHAT MEN BY VARIOUS WAYS ARRIVE AT THE SAME END.

CHAPTER IIOF SORROW

CHAPTER IIITHAT OUR AFFECTIONS CARRY THEMSELVES BEYOND US

CHAPTER IVTHAT THE SOUL EXPENDS ITS PASSIONS UPON FALSE OBJECTS

CHAPTER VWHETHER THE GOVERNOR HIMSELF GO OUT TO PARLEY

CHAPTER VITHAT THE HOUR OF PARLEY DANGEROUS

CHAPTER VIITHAT THE INTENTION IS JUDGE OF OUR ACTIONS

CHAPTER VIIIOF IDLENESS

CHAPTER IXOF LIARS

CHAPTER XOF QUICK OR SLOW SPEECH

CHAPTER XIOF PROGNOSTICATIONS

CHAPTER XIIOF CONSTANCY

CHAPTER XIIITHE CEREMONY OF THE INTERVIEW OF PRINCES

CHAPTER XIVTHAT MEN ARE JUSTLY PUNISHED FOR BEING OBSTINATE

CHAPTER XVOF THE PUNISHMENT OF COWARDICE

CHAPTER XVIA PROCEEDING OF SOME AMBASSADORS

CHAPTER XVIIOF FEAR

CHAPTER XVIIINOT TO JUDGE OF OUR HAPPINESS TILL AFTER DEATH.

CHAPTER XIXTHAT TO STUDY PHILOSOPY IS TO LEARN TO DIE

CHAPTER XXOF THE FORCE OF IMAGINATION

CHAPTER XXITHAT THE PROFIT OF ONE MAN IS THE DAMAGE OF ANOTHER

CHAPTER XXIIOF CUSTOM; WE SHOULD NOT EASILY CHANGE A LAW RECEIVED

CHAPTER XXIIIVARIOUS EVENTS FROM THE SAME COUNSEL

CHAPTER XXIVOF PEDANTRY

CHAPTER XXVOF THE EDUCATION OF CHILDREN

CHAPTER XXVIFOLLY TO MEASURE TRUTH AND ERROR BY OUR OWN CAPACITY

CHAPTER XXVIIOF FRIENDSHIP

CHAPTER XXVIIININE AND TWENTY SONNETS OF ESTIENNE DE LA BOITIE

CHAPTER XXIXOF MODERATION

CHAPTER XXXOF CANNIBALS

CHAPTER XXXITHAT A MAN IS SOBERLY TO JUDGE OF THE DIVINE ORDINANCES

CHAPTER XXXIIWE ARE TO AVOID PLEASURES, EVEN AT THE EXPENSE OF LIFE

CHAPTER XXXIIIFORTUNE IS OFTEN OBSERVED TO ACT BY THE RULE OF REASON

CHAPTER XXXIVOF ONE DEFECT IN OUR GOVERNMENT

CHAPTER XXXVOF THE CUSTOM OF WEARING CLOTHES

CHAPTER XXXVIOF CATO THE YOUNGER

CHAPTER XXXVIITHAT WE LAUGH AND CRY FOR THE SAME THING

CHAPTER XXXVIII OF SOLITUDE

CHAPTER XXXIXA CONSIDERATION UPON CICERO

CHAPTER XLRELISH FOR GOOD AND EVIL DEPENDS UPON OUR OPINION

CHAPTER XLINOT TO COMMUNICATE A MAN'S HONOUR

CHAPTER XLIIOF THE INEQUALITY AMOUNGST US.

CHAPTER XLIIIOF SUMPTUARY LAWS

CHAPTER XLIVOF SLEEP

CHAPTER XLVOF THE BATTLE OF DREUX

CHAPTER XLVIOF NAMES

CHAPTER XLVIIOF THE UNCERTAINTY OF OUR JUDGMENT

CHAPTER XLVIIIOF WAR HORSES, OR DESTRIERS

CHAPTER XLIXOF ANCIENT CUSTOMS

CHAPTER LOF DEMOCRITUS AND HERACLITUS

CHAPTER LIOF THE VANITY OF WORDS

CHAPTER LIIOF THE PARSIMONY OF THE ANCIENTS

CHAPTER LIIIOF A SAYING OF CAESAR

CHAPTER LIVOF VAIN SUBTLETIES

CHAPTER LVOF SMELLS

CHAPTER LVIOF PRAYERS

CHAPTER LVIIOF AGE

BOOK THE SECOND

CHAPTER IOF THE INCONSTANCY OF OUR ACTIONS

CHAPTER IIOF DRUNKENNESS

CHAPTER IIIA CUSTOM OF THE ISLE OF CEA

CHAPTER IVTO-MORROW'S A NEW DAY

CHAPTER VOF CONSCIENCE

CHAPTER VIUSE MAKES PERFECT

CHAPTER VIIOF RECOMPENSES OF HONOUR

CHAPTER VIIIOF THE AFFECTION OF FATHERS TO THEIR CHILDREN

CHAPTER IXOF THE ARMS OF THE PARTHIANS

CHAPTER XOF BOOKS

CHAPTER XIOF CRUELTY

CHAPTER XIIIOF JUDGING OF THE DEATH OF ANOTHER

CHAPTER XIVTHAT OUR MIND HINDERS ITSELF

CHAPTER XVTHAT OUR DESIRES ARE AUGMENTED BY DIFFICULTY

CHAPTER XVIOF GLORY

CHAPTER XVIIOF PRESUMPTION

CHAPTER XVIIIOF GIVING THE LIE

CHAPTER XIXOF LIBERTY OF CONSCIENCE

CHAPTER XXTHAT WE TASTE NOTHING PURE

CHAPTER XXIAGAINST IDLENESS

CHAPTER XXIIOF POSTING

CHAPTER XXIIIOF ILL MEANS EMPLOYED TO A GOOD END

CHAPTER XXIVOF THE ROMAN GRANDEUR

CHAPTER XXVNOT TO COUNTERFEIT BEING SICK

CHAPTER XXVIOF THUMBS

CHAPTER XXVIICOWARDICE THE MOTHER OF CRUELTY

CHAPTER XXVIIIALL THINGS HAVE THEIR SEASON

CHAPTER XXIXOF VIRTUE

CHAPTER XXXOF A MONSTROUS CHILD

CHAPTER XXXIOF ANGER

CHAPTER XXXIIDEFENCE OF SENECA AND PLUTARCH

CHAPTER XXXIII THE STORY OF SPURINA

CHAPTER XXXIVOBSERVATION ON A WAR ACCORDING TO JULIUS CAESAR

CHAPTER XXXVOF THREE GOOD WOMEN

CHAPTER XXXVIOF THE MOST EXCELLENT MEN

CHAPTER XXXVIIOF THE RESEMBLANCE OF CHILDREN TO THEIR FATHERS

BOOK THE THIRD

CHAPTER IOF PROFIT AND HONESTY

CHAPTER IIOF REPENTANCE

CHAPTER IIIOF THREE COMMERCES

CHAPTER IVOF DIVERSION

CHAPTER VUPON SOME VERSES OF VIRGIL

CHAPTER VIOF COACHES

CHAPTER VIIOF THE INCONVENIENCE OF GREATNESS

CHAPTER VIII OF THE ART OF CONFERENCE

CHAPTER IXOF VANITY

CHAPTER XOF MANAGING THE WILL

CHAPTER XIOF CRIPPLES

CHAPTER XIIOF PHYSIOGNOMY

CHAPTER XIIIOF EXPERIENCE APOLOGY

PROJECT GUTENBERG EDITOR'S BOOKMARKS

Homo svm: hvmani nil a me alienvm puto. (I am a man: nothing that affects man do I think foreign to me). – Terence. Divider ...

蒙田

维基百科,自由的百科全书

蒙田[1](Michel de Montaigne,1533年2月28日-1592年9月13日),文艺复兴时期法国作家,以《尝试集》[2](Essais)三卷留名后世。《尝试集》在西方文学史上占有重要地位,作者另辟新径,不避谦疑大谈自己,开卷即说:“吾书之素材无他,即吾人也。”(je suis moy-mesmes la matiere de mon livre.)[3]

目录 |

生平

生于波尔多附近的佩里戈尔(现在的多尔多涅省),为家中长子。家族为殷实商人,从事鱼、酒的国际贸易。家中信奉天主教,蒙田一生坚持旧教信仰,但有几个弟妹后改奉新教。其父在意大利当过兵,吸收了一些新颖的教育思想。六岁以前寄宿在农村家庭,以农民夫妇为教父母,并由只说拉丁文的老师教导,因此以拉丁文为母语。少年时代,在吉耶讷学院(Collège de Guyenne)习希腊文、法文、修辞术,因拉丁语流利,多在拉丁剧中担任主角;后来到图卢兹(一说巴黎)习法律。1557年起在波尔多最高法院(Parlement de Bordeaux)任职,并认识博埃蒂(Étienne de la Boétie),成为莫逆。1561年至1563年在查理九世的宫廷出入。1563年博埃蒂离世,大受打击。1565年成婚,儿女多夭折,唯一女长成。1568年父亲离世,袭其封号与领地,成一家之主。1571年起退居蒙田堡(Château de Montaigne),潜心写作。

宗教内战期间,为旧教的亨利三世和新教的纳瓦拉的亨利居间调停。1578年起为肾石所困扰,1580年至1581年游法国、德国、奥地利、瑞士、意大利等地,散心之余,寻找疗法。回国后出任波尔多市长直至1585年,并继续增修《尝试集》。59岁病逝于蒙田堡。

[编辑] 作品

首两卷《尝试集》在1580年出版,三卷版付梓于1588年,死前蒙田还在病榻上增订该书。学者习惯将蒙田的思想分为三个阶段(尽管未必准确):斯多噶时期(1572─74年)、怀疑主义危机(1576年)、伊壁鸠鲁时期(1578-92年)。三个阶段的思想也粗略反映在三卷《尝试集》中,卷二的〈为塞朋德辩护〉(Apologie de Raymond Sebond)一文,被认为代表了蒙田的怀疑主义思想,该篇也是《尝试集》里最长的一篇(后世很多出版商将这一篇独立成书)。

后人也将蒙田的《旅游日志》(Journal de voyage)和书信(现存39封)整理、出版。

In 1578, Montaigne, whose health had always been excellent, started suffering from painful kidney stones, a sickness he had inherited from his father's family. Throughout this illness, he would have nothing to do with doctors or drugs.[18] From 1580 to 1581, Montaigne traveled in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, partly in search of a cure, establishing himself at Bagni di Lucca where he took the waters. His journey was also a pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto, to which he presented a silver relief depicting himself and his wife and daughter kneeling before the Madonna, considering himself fortunate that it should be hung on a wall within the shrine.[19] He kept a fascinating journal recording regional differences and customs and a variety of personal episodes, including the dimensions of the stones he succeeding in ejecting from his bladder. This was published much later, in 1774, after its discovery in a trunk which is displayed in his tower.[20]

While travelling through Rome in 1581 Montaigne was detained in order to have the text of his Essais examined by Sisto Fabri who served as Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Gregory XIII. After Fabri examined Montaigne's Essais the text was returned to its author on 20 March, 1581. Montaigne had apologized for references to the pagan notion of "fortuna" as well as for writing favorably of Julian the Apostate and of heretical poets, and was released to follow his own conscience in making emendations to the text.[21]

可惜這本書沒附地圖 以致讀起來如墜入時空的迷霧中

蒙田意大利之旅

- 出版日期:2011年08月01日

- 語言:簡體中文

譯者:馬振騁

出版社:上海書店出版社

譯序

意大利之旅

穿越法國去瑞士(一五八○年九月五日—十八日)

瑞士(一五八○年九月二十九日—十月七日)

德意志、奧地利和阿爾卑斯地區(一五八○年十月八日—二十七日)

意大利,去羅馬的路上(一五八○年十月二十八日—十一月二十九日)

意大利︰羅馬(一五八○年十一月三十日—一五八一年四月十九日)

意大利︰從羅馬到洛雷托和拉維拉(一五八一年四月十九日—五月七日)

意大利︰初訪拉維拉(一五八一年五月七日—六月二十一日)

意大利︰佛羅倫薩—比薩—盧卡(一五八一年六月二十一日—八月十三日)

意大利︰第二次逗留拉維拉(一五八一年八月十四日—九月十二日)

書信

序文

○一 致安東尼‧迪普拉先生,巴黎市長

○二 致父親的信

○三 致蒙田大人閣下

○四 致亨利‧德‧梅姆閣下

○五 致洛比塔爾大人

○六 致朗薩克先生

○七 告讀者

○八 致保爾‧德‧弗瓦先生

○九 致吾妻蒙田夫人

一○ 致波爾多市市政官先生們

一一 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一二 致南都依埃大人

一三 呈亨利三世國王

一四 呈那瓦爾國王

一五 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一六 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

一七 致杜布依先生

一八 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一九 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二 致波爾多市市政官先生們

二一 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二二 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二四 致波爾多市市政官先生們

二五 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二六 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二七 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二八 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二九 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三一 致波爾多市市政官先生們

三二 致波爾多市市政官先生們

三三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三四 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三五 致波爾米埃夫人

三六 致安東尼‧盧瓦澤爾先生

三七 呈亨利四世國王

三八 致M

三九 呈亨利四世國王

家庭紀事

序文

紀事

書房格言

序文

格言

意大利之旅

穿越法國去瑞士(一五八○年九月五日—十八日)

瑞士(一五八○年九月二十九日—十月七日)

德意志、奧地利和阿爾卑斯地區(一五八○年十月八日—二十七日)

意大利,去羅馬的路上(一五八○年十月二十八日—十一月二十九日)

意大利︰羅馬(一五八○年十一月三十日—一五八一年四月十九日)

意大利︰從羅馬到洛雷托和拉維拉(一五八一年四月十九日—五月七日)

意大利︰初訪拉維拉(一五八一年五月七日—六月二十一日)

意大利︰佛羅倫薩—比薩—盧卡(一五八一年六月二十一日—八月十三日)

意大利︰第二次逗留拉維拉(一五八一年八月十四日—九月十二日)

書信

序文

○一 致安東尼‧迪普拉先生,巴黎市長

○二 致父親的信

○三 致蒙田大人閣下

○四 致亨利‧德‧梅姆閣下

○五 致洛比塔爾大人

○六 致朗薩克先生

○七 告讀者

○八 致保爾‧德‧弗瓦先生

○九 致吾妻蒙田夫人

一○ 致波爾多市市政官先生們

一一 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一二 致南都依埃大人

一三 呈亨利三世國王

一四 呈那瓦爾國王

一五 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一六 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

一七 致杜布依先生

一八 致馬蒂尼翁大人

一九 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二 致波爾多市市政官先生們

二一 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二二 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二四 致波爾多市市政官先生們

二五 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二六 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二七 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二八 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

二九 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三一 致波爾多市市政官先生們

三二 致波爾多市市政官先生們

三三 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三四 致馬蒂尼翁元帥

三五 致波爾米埃夫人

三六 致安東尼‧盧瓦澤爾先生

三七 呈亨利四世國王

三八 致M

三九 呈亨利四世國王

家庭紀事

序文

紀事

書房格言

序文

格言

[编辑] 评价

- 爱默生在日记中提到《尝试集》:“剖开这些字,会有血流出来;那是有血管的活体。” (Cut these words, and they would bleed; they are vascular and alive.)[4]

- 尼采谈到蒙田:“世人对生活的热情,由于这样一个人的写作而大大提高了。” (Dass ein solcher Mensch geschrieben hat, dadurch ist wahrlich die Lust auf dieser Erde zu leben vermehrt worden.)[5]

[编辑] 注释

- ^ 全名为蒙田领主米歇尔‧埃康(Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne),“米歇尔”为名,“埃康”为姓,“蒙田领主”则是世袭封号。

- ^ 或译为《试笔》,但中文世界一般译为《随笔》。

- ^ 见《尝试集》开卷的“致读者”("au lecteur")。

- ^ Bliss Perry, ed., The Heart of Emerson's Journals, p.54.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, "Schopenhauer als Erzieher", in Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen.

[编辑] 外部链接

| 从维基姊妹计划了解更多有关“蒙田”的内容: | |

|---|---|

| 维基词典上的字词解释 | |

| 维基教科书上的教科书和手册 | |

| 维基语录上的名言 | |

| 维基文库上的源文 | |

| 维基共享资源上的多媒体资源 | |

| 维基新闻上的新闻 | |

- (法语) 《尝试集》原文(可以用关键字来搜寻)

- (法语) 蒙田之友国际学会的网站

- (法语) 蒙田堡的旅游网站

- (英文) 图集:蒙田堡、蒙田的书房、墓地,留意刻在书房梁柱上的拉丁箴言

- (法语) Montaigne by Sollers

蒙田《随筆集》內也有許多教育學等方面的宏文.....

蒙田的政治学:《随筆集》中的權威與治理

编辑推荐

编辑推荐

《蒙田的政治学》为蒙田的政治理论(以及实践)提供了一份清晰易懂的概述,更提出了新的见解。作者对蒙田的《随笔集》、与其有关的二级文献及历史背景均了如指掌。

——安托万·孔帕尼翁(Antoine Compagnon),哥伦比亚大学和索邦大学

这部构思精巧的作品填补了学术上一项重大的空白。书中运用的历史和文本材料以及参考文献皆十分充实,富于启发性。作品涵盖的领域广泛,论述极具深度。

——麦克尔·莫里亚蒂(MichaelMoriarty),伦敦大学玛丽女王学院

通过详尽地展现《随笔集》的政治与历史背景,冯塔纳使我们能够更容易地理解蒙田,理解他那超越了他所处时代和立场的政治哲学与他对于那个时代和立场不得不表达的话语之间的关系。

——安·哈特尔(Ann Hartle),《政治学评论》

——安托万·孔帕尼翁(Antoine Compagnon),哥伦比亚大学和索邦大学

这部构思精巧的作品填补了学术上一项重大的空白。书中运用的历史和文本材料以及参考文献皆十分充实,富于启发性。作品涵盖的领域广泛,论述极具深度。

——麦克尔·莫里亚蒂(MichaelMoriarty),伦敦大学玛丽女王学院

通过详尽地展现《随笔集》的政治与历史背景,冯塔纳使我们能够更容易地理解蒙田,理解他那超越了他所处时代和立场的政治哲学与他对于那个时代和立场不得不表达的话语之间的关系。

——安·哈特尔(Ann Hartle),《政治学评论》

内容简介

内容简介

本

书运用翔实的史料和文献,清晰地勾勒出蒙田在16世纪法国宗教战争中的政治活动及其对《随笔集》创作的影响,将蒙田对社会现实和政治、法律实践的洞见置于

欧洲政治思想发展的脉络之中,令人信服地呈现出蒙田的政治思想和立场,论证了《随笔集》可能是欧洲进入基督教时期后第一部全面批判权威,坚定捍卫个人自

主、信仰自由与宗教宽容等现代自由主义价值观的重要作品,并且无论在体裁、方法还是见解上都是特立独行的。作者反驳了传统评论对蒙田的误解,为解读《随笔

集》这部不朽的经典提供了全新的视角和启迪。

作者简介

作者简介

边

凯玛里亚·冯塔纳(Biancamaria Fontana),瑞士洛桑大学政治思想史教授。 主要著作: 《商业社会政治学的再思考》

(Rethinking the Politics ofCommercial Society)

《本杰明·贡斯当和大革命之后的思想》 (Benjamin Constant and the Post—Revolutionary

Mind)

目录

目录

导言

第一章 法的精神

第二章 一个沉重的世纪:美德的衰落

第三章 信仰自由:关于宽容的政治策略

第四章 信仰自由:对舆论的治理

第五章 改变舆论倾向:信任与正当性

第六章 从经验中学习:作为实践的政治

结论 蒙田的遗产

参考文献

索引

凡例

译后记

By Robert Zaretsky

Mr. Zaretsky is a historian and author.

June 28, 2020

In the summer of 1585, the mayor of Bordeaux learned, from the comfort of his nearby chateau, that the bubonic plague had burst upon his city. Those who could were fleeing, he was told, while those who could not were “dying like flies.” What to do? His term in office, on the one hand, was nearly over and his last official duty was to attend the transition ceremony. On the other hand, perhaps his duty was with those still inside the city walls.

Both hands on the reins of his horse, the mayor rode to the city’s edge and wrote to the municipal council to ask whether his life was worth a transition ceremony. He did not seem to receive a reply and returned to his chateau. By the time the plague subsided, more than 14,000 people — about a third of the city’s population — had died horrible deaths. As for the former mayor, he returned to a far more pressing task: the writing of essays.

The mayor was Michel de Montaigne. Known today as the author of the “Essays,” the classic of self-reflection and self-knowing, Montaigne was better perhaps known in his own lifetime as a man of politics. Yet his efforts — quite literally, his essais — at politics and his essais at portraying himself are not unrelated. In both cases, Montaigne probed the limits of what he could do in the world and what he could know about himself.

Bordeaux was a hot spot for both bacteriological and theological plagues in the late 1500s. The wars of religion, a series of eight distinct conflicts between Catholics and Protestants — replete with massacres on both sides — had ravaged France between 1562 and 1598. As both mayor and diplomat, Montaigne tried several times to broker accords between the two sides. He was known (and despised) by both sides as a politique: someone who, for the sake of all, tried to find common ground in a land savaged by zealotry.

In this, Montaigne never succeeded yet he was not one to waste a plague. In his essay “On Physiognomy,” written in 1585, he described the wars as “profitable disasters.” The mutual butcheries, in effect, prepared him for the next plague. The cruelty and fury, ambition and avarice that consumed both sides taught him “to rely on myself in distress.”

The trick, though, was to first find that self. Or, more accurately, to found that self. In effect, as he wrote and rewrote his essays until his death in 1592, Montaigne wrote and rewrote his own self. In “On Giving the Lie,” he observed the strange alchemy between paper and person, between writing one’s life and becoming that life: “I have no more made my book than my book has made me — a book consubstantial with its author.”

More than a millennium earlier, thinkers like Epicurus and Seneca had already mapped out this path. Inscribing their words on the pages of his essays — as well as in the roof beams of his library — Montaigne grasped that, unlike philosophers in his day (or our own), these teachers sought not to inform their students, but instead to form them. As the classical scholar Pierre Hadot has argued, Stoicism and Epicureanism offered not airy abstractions but real-world “spiritual exercises.” Though the methods of these school varied, their mission was the same: to teach students how to master physics and ethics not as an end, but as the means to master their own selves and so better deal with life’s daily challenges, no less than its sudden catastrophes.

Yet self-mastery was itself a means to a greater end: the aligning of the self with the world. The recognition of reality — of what can and cannot be changed — teaches the need for self-control. This “plague of the utmost severity” in 1585 challenged Montaigne’s self-mastery even more than the wars did. When the pestilence reached his estate, he fled with his family in order to protect them. From the road, he recalled, he saw peasants digging their own graves.

We will never know what these men and women thought when they saw Montaigne and his household pass them on their horses and carriages. But what should we think? For many critics, Montaigne was, if not clearly a coward, less than a hero: Imagine if Mayor Bill De Blasio, learning that New York City had been struck by the coronavirus while he was vacationing in the Berkshires, had emailed the City Council to wish them good luck. Yet we need to remember that Montaigne never pretended or sought to be a hero. Instead, he sought to do what could be done — in this case, save his family — and sought to find what could be found in this experience.

Editors’ Picks

3 Long (Haired) Months: Barbershop Before-and-Afters

What’s Gotten Into the Price of Cheese?

Overlooked No More: Valerie Solanas, Radical Feminist Who Shot Andy Warhol

Continue reading the main story

In the end, what he found was the essay — less the masterpiece he had written, though, than the life he had lived. In the many essays of his life he discovered the importance of the moderate life. In his final essay, “On Experience,” Montaigne reveals that “greatness of soul is not so much pressing upward and forward as knowing how to circumscribe and set oneself in order.” What he finds, quite simply, is the importance of the moderate life. We must then, he writes, “compose our character, not compose books.” There is nothing paradoxical about this because his literary essays helped him better essay his life. The lesson he takes from this trial might be relevant for our own trial: “Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live properly.”

第一章 法的精神

第二章 一个沉重的世纪:美德的衰落

第三章 信仰自由:关于宽容的政治策略

第四章 信仰自由:对舆论的治理

第五章 改变舆论倾向:信任与正当性

第六章 从经验中学习:作为实践的政治

结论 蒙田的遗产

参考文献

索引

凡例

译后记

By Robert Zaretsky

Mr. Zaretsky is a historian and author.

June 28, 2020

In the summer of 1585, the mayor of Bordeaux learned, from the comfort of his nearby chateau, that the bubonic plague had burst upon his city. Those who could were fleeing, he was told, while those who could not were “dying like flies.” What to do? His term in office, on the one hand, was nearly over and his last official duty was to attend the transition ceremony. On the other hand, perhaps his duty was with those still inside the city walls.

Both hands on the reins of his horse, the mayor rode to the city’s edge and wrote to the municipal council to ask whether his life was worth a transition ceremony. He did not seem to receive a reply and returned to his chateau. By the time the plague subsided, more than 14,000 people — about a third of the city’s population — had died horrible deaths. As for the former mayor, he returned to a far more pressing task: the writing of essays.

The mayor was Michel de Montaigne. Known today as the author of the “Essays,” the classic of self-reflection and self-knowing, Montaigne was better perhaps known in his own lifetime as a man of politics. Yet his efforts — quite literally, his essais — at politics and his essais at portraying himself are not unrelated. In both cases, Montaigne probed the limits of what he could do in the world and what he could know about himself.

Bordeaux was a hot spot for both bacteriological and theological plagues in the late 1500s. The wars of religion, a series of eight distinct conflicts between Catholics and Protestants — replete with massacres on both sides — had ravaged France between 1562 and 1598. As both mayor and diplomat, Montaigne tried several times to broker accords between the two sides. He was known (and despised) by both sides as a politique: someone who, for the sake of all, tried to find common ground in a land savaged by zealotry.

In this, Montaigne never succeeded yet he was not one to waste a plague. In his essay “On Physiognomy,” written in 1585, he described the wars as “profitable disasters.” The mutual butcheries, in effect, prepared him for the next plague. The cruelty and fury, ambition and avarice that consumed both sides taught him “to rely on myself in distress.”

The trick, though, was to first find that self. Or, more accurately, to found that self. In effect, as he wrote and rewrote his essays until his death in 1592, Montaigne wrote and rewrote his own self. In “On Giving the Lie,” he observed the strange alchemy between paper and person, between writing one’s life and becoming that life: “I have no more made my book than my book has made me — a book consubstantial with its author.”

More than a millennium earlier, thinkers like Epicurus and Seneca had already mapped out this path. Inscribing their words on the pages of his essays — as well as in the roof beams of his library — Montaigne grasped that, unlike philosophers in his day (or our own), these teachers sought not to inform their students, but instead to form them. As the classical scholar Pierre Hadot has argued, Stoicism and Epicureanism offered not airy abstractions but real-world “spiritual exercises.” Though the methods of these school varied, their mission was the same: to teach students how to master physics and ethics not as an end, but as the means to master their own selves and so better deal with life’s daily challenges, no less than its sudden catastrophes.

Yet self-mastery was itself a means to a greater end: the aligning of the self with the world. The recognition of reality — of what can and cannot be changed — teaches the need for self-control. This “plague of the utmost severity” in 1585 challenged Montaigne’s self-mastery even more than the wars did. When the pestilence reached his estate, he fled with his family in order to protect them. From the road, he recalled, he saw peasants digging their own graves.

We will never know what these men and women thought when they saw Montaigne and his household pass them on their horses and carriages. But what should we think? For many critics, Montaigne was, if not clearly a coward, less than a hero: Imagine if Mayor Bill De Blasio, learning that New York City had been struck by the coronavirus while he was vacationing in the Berkshires, had emailed the City Council to wish them good luck. Yet we need to remember that Montaigne never pretended or sought to be a hero. Instead, he sought to do what could be done — in this case, save his family — and sought to find what could be found in this experience.

Editors’ Picks

3 Long (Haired) Months: Barbershop Before-and-Afters

What’s Gotten Into the Price of Cheese?

Overlooked No More: Valerie Solanas, Radical Feminist Who Shot Andy Warhol

Continue reading the main story

In the end, what he found was the essay — less the masterpiece he had written, though, than the life he had lived. In the many essays of his life he discovered the importance of the moderate life. In his final essay, “On Experience,” Montaigne reveals that “greatness of soul is not so much pressing upward and forward as knowing how to circumscribe and set oneself in order.” What he finds, quite simply, is the importance of the moderate life. We must then, he writes, “compose our character, not compose books.” There is nothing paradoxical about this because his literary essays helped him better essay his life. The lesson he takes from this trial might be relevant for our own trial: “Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live properly.”

Robert Zaretsky is a professor at the University of Houston and the author of, most recently, “Catherine & Diderot: The Empress, the Philosopher, and the Fate of the Enlightenment,” and the forthcoming “The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas.

As disease and war ravaged the nation, he left town and invented the essay.

Montaigne Fled the Plague, and Found Himself

沒有留言:

張貼留言