Leo Tolstoy was born on September 9th, 1828. The Russian author achieved world fame with novels like "Anna Karenina " (1878) or "War and Peace" (1868/9). Many German authors, such as Thomas Mann or Bertolt Brecht, revered him. In many of his works, Tolstoy criticized aristocratic society and highlighted the plight of the poor rural population in tsarist Russia. He was an advocate of non-violent resistance and charity.

****

Rereading “War and Peace”, Tolstoy felt “repentance and shame...not unlike what a man experiences when he sees the remains of an orgy in which he has taken part”

Professor of Creative Writing Yiyun Li has had an interesting journey.

She started with a bachelor's degree in cell biology from Peking University. ➡️ Next, she came to the U.S. to study immunology at University of Iowa. ➡️ Then, she switched gears, earning MFAs in fiction writing and creative nonfiction.

Now, as an author and professor, we wanted to get her insights on writing, her favorite apps and how she creates storylines in her works.

This is only me, being very nerdy. Sometimes I hand-copy passages from “War and Peace.” I also read “War and Peace” and “Moby Dick” once a year. I feel everything I want from literature can be found in these two books. “War and Peace” is such an epic, but then you can go to one paragraph, just to see how Tolstoy portrays a little girl, picking up a fruit from a tree. Tolstoy is a democratic seer; he sees everything. “Moby Dick” is the epitome of metaphors: the ocean, the whale, the experience makes me feel large.

"The cudgel of the people's war was lifted with all its menacing and majestic might, and caring nothing for good taste and procedure, with dull-witted simplicity but sound judgement it rose and fell, making no distinctions." - Leo Tolstoy

Have you ever wanted to read 'War and Peace' but find this magnificent novel somewhat daunting? Our audio guide presented by Amy Mandelker suggests ways of approaching this masterpiece for first-time readers. Amy is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

"Perhaps having intuited Tolstoy’s disdain for ambition, the creators of the BBC series focused most of their attention on the realm of home. The disease of Napoleonism is largely absent from the Davies adaptation, where Napoleon emerges as a pedestrian villain. In minimizing Napoleon and the Napoleonic quest, the series’s directors domesticate male characters, robbing them of the outward ambition so apparent in Tolstoy’s novel: Andrei (James Norton) seems bored and restless, while Pierre’s (Paul Dano) primary motivation appears to be a very contemporary kind of anxiety."

東方白的文學回憶錄【真與美】末卷,有專文介紹他與夫人訪此莊園的感動........

War and peaceful gardens: in the land of Tolstoy

A visit to Tolstoy’s country estate gives writer and gardener Charlotte Mendelson an insight into the relationship between nature and creativity

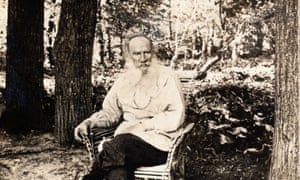

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/Getty

Country life … Tolstoy in the grounds of his estate, Yasnaya Polyana. Photograph: George Rinhart/Corbis/GettyCharlotte Mendelson

Saturday 15 October 2016 11.00 BST

Springtime can kill you, but autumn is worse. If one’s soul responds to nature – and, as Louis Armstrong said of jazz, if you have to ask what that means, you’ll never know – then its beauty is painful. Whatever TS Eliot thought (the poor man was wrong about so much), autumn is the most painful time of all. Walking in the grounds of Tolstoy’s country estate at Yasnaya Polyana, yellow birch leaves turning gently as they fall, is almost too much, particularly for an oversensitive novelist. Five of us are here, imported by the British Council to broaden Russian conceptions of British literature. We have worked – by God we have worked – but, this morning, among the wooded paths and ripe, rich leaf mould, nothing else seems to matter, not even fiction.

For cramped city-dwellers, the incomprehensible excess of space is dazzling: the “cascade of three ponds”, each more invitingly cool and swimmable than the last; the fir woods thick with fungal life; the juicy grass. Even the ponies have had a surfeit. There is so much silken birch bark, pinkly tender beneath its epidermis; so many fallen, unregarded apples and ancient, lichen-spattered branches: mustard, pigeon, rose. One wants to sniff and wallow; at least, I do. Surely this is normal? A reasonable response to being knee-deep in the dew and bracken: surrendering to the space, the wildness?

Of course not. My fellow writers return home with translators’ business cards and ecclesiastical souvenirs. My case is full of Japanese quinces, oak leaves, almond shells, calendula seeds and, most worrying of all, a knobbly fir branch, as long as my arm, stolen from the forest floor and slipped past the cold-eyed, epauletted customs boys at Domodedovo airport. Did the other novelists find themselves embarrassingly weeping at the perfect transparency of a plantation of firs, bare-trunked and widely spaced to allow, as Sofia and Leo Tolstoy had intended, the pale September sunlight to pour in? They did not.

***

Like his grandfather, Prince Volkonsky, who first developed the estate in Tula region, 120 miles south of Moscow, Leo Tolstoy was an enthusiast. His wife, Sofia, may also have been, in her spare moments between bearing his 13 children, copying and editing War and Peace seven times and documenting every minute of their lives in diaries and photographs. Sofia’s husband had no time for such fripperies. He was busy, trying to create a new breed of horse by crossing English thoroughbred stallions with their Kirgizian cousins; following developments in fruit-tree breeding; buying Japanese pigs (“I feel I cannot be happy in life until I get some of my own”); downing healthy bowlfuls of fermented mare’s milk; maddening Sofia with his “purely verbal” renunciation of worldly goods; spending too many roubles on attempting to grow watermelons, coffee and pineapples in his hothouse. Anything, one suspects, could have captured his attention: dog-racing, topiary, needlepoint.

Tolstoy derided his early works as an awkward mixture of fact and fiction, yet they offer an insight into what made him

But, although it’s easy to dismiss him as a Professor Branestawm crank, to laugh at the old man who lifted weights in his study and hung, red-faced, from a bar while instructing his staff, Tolstoy’s passionate engagement with the land around him was his life’s joy. Like all but the unluckiest children, even today, he knew the tannic bite of currant leaves, the rumpled gloss of worm casts, the hayish sweetness of a grass stem. Childhood, boyhood, youth is thick with the sensual thrills of the outdoors: the damply shaded raspberry thicket, alive with sparrows, and the taste of accidentally ingested wood beetles, the cobwebs, the dense, dank soil. And, even though he famously derided his early works as “an awkward mixture of fact and fiction”, they offer a moving insight into what made him.

Monet wrote: “Je dois peut-être aux fleurs d’avoir été peintre” – I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers. Writers are often asked what made them write; I can’t answer that for myself, let alone for Monet, but, surely, the intense feelings evoked by colour and form made him need to express himself, in paint. He also became a wonderful gardener. Edith Wharton’s first published short story, Mrs Manstey’s View, describes how a glimpse of shabby town garden is all that keeps old Mrs Mantsey alive. Later, of the grand Italianate gardens, all rustic rock fountains and pleaching, which she designed for The Mount, her home in Massachusetts, she wrote: “I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist, and this place, every line of which is my own work, far surpasses The House of Mirth.”

Wharton was wrong about the novels, and The Mount is too neat for me: where is the sledge requisitioned as a plant crutch? However, we would agree, I think, about the soothing power of gardens: loneliness and sadness are horrible, but they feed us, teach us to comfort ourselves with alertness, and to look – what the poet Mary Oliver calls paying attention. When at school I encountered Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “worlds of wanwood leafmeal” in “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child”, or Laurie Lee’s morning in “April Rise” – “lemon-green the vaporous morning drips / wet sunlight on the powder of my eye” – I recognised that precision, the thrilling focus on nature, close up. Don’t other children, on the rare occasions when they’re not reading, fall in love with the blistered, sun-warmed paint on a door, the beauty of old, lichened bricks, or susurrating grasses? We didn’t have grateful serfs or 100 acres of orchards, but there were new worlds among the wild strawberries and, possibly, ichthyosaur bones in the sandpit.

I had no interest in gardens until my mid-30s but, I now realise, I had fallen in love with leaves, twigs and decay long ago, and it made me need to write. Tolstoy may have found apiaries so absorbing, he claimed he could barely remember the author of The Cossacks but, as he told an old friend: “Whatever I do, somewhere between the dung and the dirt I keep starting to weave words.”

***Count Tolstoy would probably not have recognised my tiny outdoor space as a garden. Largely paved, entirely overlooked, without bluebells or coppicing or even a simple wildflower meadow, my six square metres of polluted soil he would consider to be unworthy of the most pitiful peasant schoolteacher: where is the pig? The walnut tree? Oh Leo, I know; I’m disappointed too.

This may be why, for me, garden writing is a sensitive subject. As a writer and a gardener, albeit of an experimental jungle allotment, the classics of domestic horticulture leave me embarrassingly cold. Gertrude Jekyll, Elizabeth von Arnim, Margery Fish, Mirabel Osler, even Christopher Lloyd, the Mae West of garden writers, all had acres, staff, greenhice. Their vision was inspiring, their metaphors exciting (I particularly love Lloyd’s division of smells into “moral and immoral”), but their rambling rhododendron groves and stone walkways were alienating to a novice. Reading about their tree‑surgery crises was like owning a carnivorous Shetland pony while reading about Olympic dressage: all very lovely but not for the likes of me. Besides, my ever more rampaging obsession was for growing fruit and vegetables, now well over 100 different kinds and the more unusual the better, yet most garden writing focused either on shrubbery and flowers, or on an alien world of double digging potato trenches, superphosphate and basic pruning, apparently a simple twice-yearly process of shortening main central leaders, side-branch leaders to the third tier and laterals, then spurring back and tying in, which, to a person unable to tell their left from their right, was of limited value.

At the other end of the gamut of garden writing lies seed catalogues: during times of stress or in deepest midwinter, they are perfect for reading in the bath. At least, they should be. But, for the novelist-gardener, trauma lies ahead. I hope I am not alone in finding certain words and phrases unbearable: “veggies”, “a bake”, “eat happy”, “hue”. Unfortunately, seed catalogues are worse, full of showy choice fluoroselect picotee bicoloured collarette pastel novelties. Perfectly ordinary varieties of flowers, fruit and vegetables bear names for which there is no excuse: Naughty Marietta, Slap ’n’ Tickle, Tendersnax, Bright Bikini, Nonstop® Rose Petticoat. They make me want to die.

Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as 'Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below'

And so, needing both comradeship and advice, I have found my gardening friends in unlikely places: horticulturally minded food writers; Joy Larkcom’s and her masterpiece, Oriental Vegetables; poor murdered Karel Čapek, author of my beloved The Gardener’s Year; and Ursula Buchan’s Garden People, for sartorial guidance. Who needs advice about vine weevils when one can gaze at photographs of interior designer and gardener Nancy Lancaster’s sexy yellow scarf, or the rakish gaucho hat of Rhoda, Lady Birley, as she firmly grips those scarlet parrot-bill loppers? Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as “Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below”, which is good enough for me.

And now, after a decade of increasingly demented growing, I have at last found my gardening sibling: Leo Tolstoy. At Yasnaya Polyana, inspecting the fat yellow squashes growing on the compost heap, sensing the curvature of the earth as we reached the bare brim of a wooded hill, I suddenly understood that in one respect, if, irritatingly, none other, I and the great beardy genius are alike. We are enthusiasts. Fine, so my garden isn’t an arrangement of colours and textures to please an artist’s, or even a normal gardener’s, eye. Who cares if it’s not reflected in any book I’ve read, or if few others garden purely for taste, smell, sensual pleasure: the warm pepper of tomato leaves, curling courgette tendrils, the corduroy ridges on a coriander seed. My tiny green and fragrant world would definitely not have been admired by Tolstoy’s guests from the drawing-room windows, but I think the man himself would have understood the passion behind it. Please ignore the broom handles and recycled windows; I’m sorry that there is nowhere to sit. But just taste this Crimean tomato, this purple bean, this golden raspberry. Look into the translucent depths of this whitecurrant. Pay attention. It brings such peace.

• Rhapsody in Green is published by Kyle Books. To order a copy for £12.99 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Monet wrote: “Je dois peut-être aux fleurs d’avoir été peintre” – I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers. Writers are often asked what made them write; I can’t answer that for myself, let alone for Monet, but, surely, the intense feelings evoked by colour and form made him need to express himself, in paint. He also became a wonderful gardener. Edith Wharton’s first published short story, Mrs Manstey’s View, describes how a glimpse of shabby town garden is all that keeps old Mrs Mantsey alive. Later, of the grand Italianate gardens, all rustic rock fountains and pleaching, which she designed for The Mount, her home in Massachusetts, she wrote: “I’m a better landscape gardener than novelist, and this place, every line of which is my own work, far surpasses The House of Mirth.”

Wharton was wrong about the novels, and The Mount is too neat for me: where is the sledge requisitioned as a plant crutch? However, we would agree, I think, about the soothing power of gardens: loneliness and sadness are horrible, but they feed us, teach us to comfort ourselves with alertness, and to look – what the poet Mary Oliver calls paying attention. When at school I encountered Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “worlds of wanwood leafmeal” in “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child”, or Laurie Lee’s morning in “April Rise” – “lemon-green the vaporous morning drips / wet sunlight on the powder of my eye” – I recognised that precision, the thrilling focus on nature, close up. Don’t other children, on the rare occasions when they’re not reading, fall in love with the blistered, sun-warmed paint on a door, the beauty of old, lichened bricks, or susurrating grasses? We didn’t have grateful serfs or 100 acres of orchards, but there were new worlds among the wild strawberries and, possibly, ichthyosaur bones in the sandpit.

I had no interest in gardens until my mid-30s but, I now realise, I had fallen in love with leaves, twigs and decay long ago, and it made me need to write. Tolstoy may have found apiaries so absorbing, he claimed he could barely remember the author of The Cossacks but, as he told an old friend: “Whatever I do, somewhere between the dung and the dirt I keep starting to weave words.”

***Count Tolstoy would probably not have recognised my tiny outdoor space as a garden. Largely paved, entirely overlooked, without bluebells or coppicing or even a simple wildflower meadow, my six square metres of polluted soil he would consider to be unworthy of the most pitiful peasant schoolteacher: where is the pig? The walnut tree? Oh Leo, I know; I’m disappointed too.

This may be why, for me, garden writing is a sensitive subject. As a writer and a gardener, albeit of an experimental jungle allotment, the classics of domestic horticulture leave me embarrassingly cold. Gertrude Jekyll, Elizabeth von Arnim, Margery Fish, Mirabel Osler, even Christopher Lloyd, the Mae West of garden writers, all had acres, staff, greenhice. Their vision was inspiring, their metaphors exciting (I particularly love Lloyd’s division of smells into “moral and immoral”), but their rambling rhododendron groves and stone walkways were alienating to a novice. Reading about their tree‑surgery crises was like owning a carnivorous Shetland pony while reading about Olympic dressage: all very lovely but not for the likes of me. Besides, my ever more rampaging obsession was for growing fruit and vegetables, now well over 100 different kinds and the more unusual the better, yet most garden writing focused either on shrubbery and flowers, or on an alien world of double digging potato trenches, superphosphate and basic pruning, apparently a simple twice-yearly process of shortening main central leaders, side-branch leaders to the third tier and laterals, then spurring back and tying in, which, to a person unable to tell their left from their right, was of limited value.

At the other end of the gamut of garden writing lies seed catalogues: during times of stress or in deepest midwinter, they are perfect for reading in the bath. At least, they should be. But, for the novelist-gardener, trauma lies ahead. I hope I am not alone in finding certain words and phrases unbearable: “veggies”, “a bake”, “eat happy”, “hue”. Unfortunately, seed catalogues are worse, full of showy choice fluoroselect picotee bicoloured collarette pastel novelties. Perfectly ordinary varieties of flowers, fruit and vegetables bear names for which there is no excuse: Naughty Marietta, Slap ’n’ Tickle, Tendersnax, Bright Bikini, Nonstop® Rose Petticoat. They make me want to die.

Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as 'Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below'

And so, needing both comradeship and advice, I have found my gardening friends in unlikely places: horticulturally minded food writers; Joy Larkcom’s and her masterpiece, Oriental Vegetables; poor murdered Karel Čapek, author of my beloved The Gardener’s Year; and Ursula Buchan’s Garden People, for sartorial guidance. Who needs advice about vine weevils when one can gaze at photographs of interior designer and gardener Nancy Lancaster’s sexy yellow scarf, or the rakish gaucho hat of Rhoda, Lady Birley, as she firmly grips those scarlet parrot-bill loppers? Noël Coward described Vita Sackville-West as “Lady Chatterley above the waist and the gamekeeper below”, which is good enough for me.

And now, after a decade of increasingly demented growing, I have at last found my gardening sibling: Leo Tolstoy. At Yasnaya Polyana, inspecting the fat yellow squashes growing on the compost heap, sensing the curvature of the earth as we reached the bare brim of a wooded hill, I suddenly understood that in one respect, if, irritatingly, none other, I and the great beardy genius are alike. We are enthusiasts. Fine, so my garden isn’t an arrangement of colours and textures to please an artist’s, or even a normal gardener’s, eye. Who cares if it’s not reflected in any book I’ve read, or if few others garden purely for taste, smell, sensual pleasure: the warm pepper of tomato leaves, curling courgette tendrils, the corduroy ridges on a coriander seed. My tiny green and fragrant world would definitely not have been admired by Tolstoy’s guests from the drawing-room windows, but I think the man himself would have understood the passion behind it. Please ignore the broom handles and recycled windows; I’m sorry that there is nowhere to sit. But just taste this Crimean tomato, this purple bean, this golden raspberry. Look into the translucent depths of this whitecurrant. Pay attention. It brings such peace.

• Rhapsody in Green is published by Kyle Books. To order a copy for £12.99 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

沒有留言:

張貼留言